The 2021-22 Graduate Traineeships are drawing to a close here in Cambridge, and what a year it’s been! From visits and talks to workshops and conferences, the Graduate Trainees have certainly been very busy. We have all learned so much about library work, both in our own academic libraries and countless other kinds of libraries – some of which we never knew existed before.

We feel very lucky to be the first cohort of Cambridge trainees to get the full Graduate Trainee experience since the COVID-19 pandemic began – although the virus did keep some of us from attending visits at various points throughout the year! But overall, we’ve managed to pack a lot in and have a more traditional Graduate Trainee experience with lots of in-person visits and training sessions. Have a look at our thread on Twitter for a round-up of the year’s activities!

Although we’ve done a lot as a group, we’ve also each had a very unique experience of being a Graduate Trainee. As such, we’ve decided to put together some personal highlights from the year, along with some information about what we’re doing next! As well as being a nice way to reflect on the year we’ve had, we hope this will give future Graduate Trainees an idea of what they can expect during their year, and the opportunities available to them after it finishes.

Ellen

“All of the visits and training opportunities have been amazing, but my personal highlight of the Graduate Traineeship has to be the connections I have made. As well as building up a really strong professional network, I have also made some friends for life here. I have a part-time job in an academic library lined up for when the traineeship ends, which offers the perfect opportunity to gain more practical experience while I study for my library Masters starting in September. I am also on the committee of a soon-to-launch network for early-career library and information professionals, which I am really excited about. I’ll be studying part-time over two years, so I should hopefully be able to maintain some level of work-life balance!”

Jess

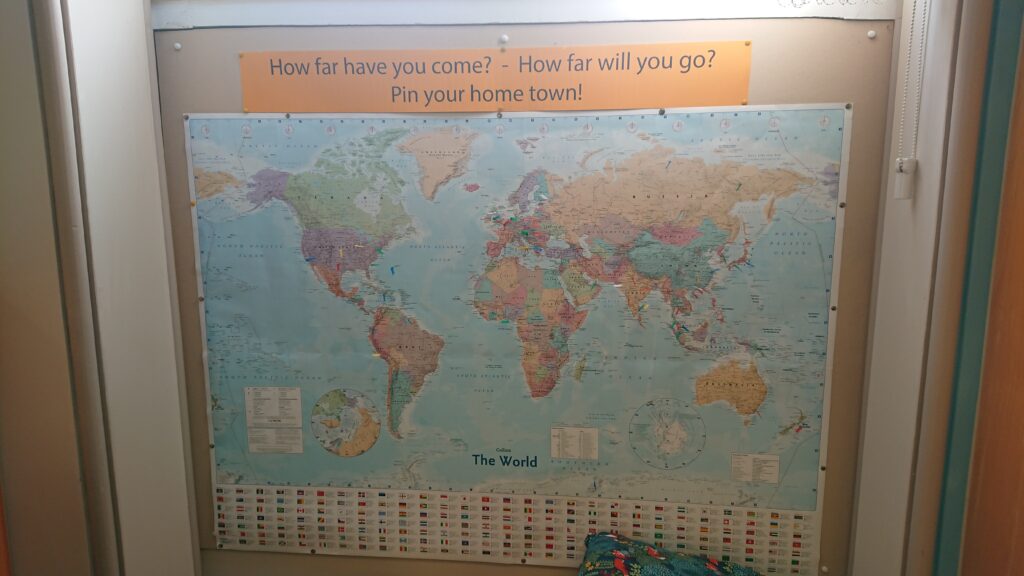

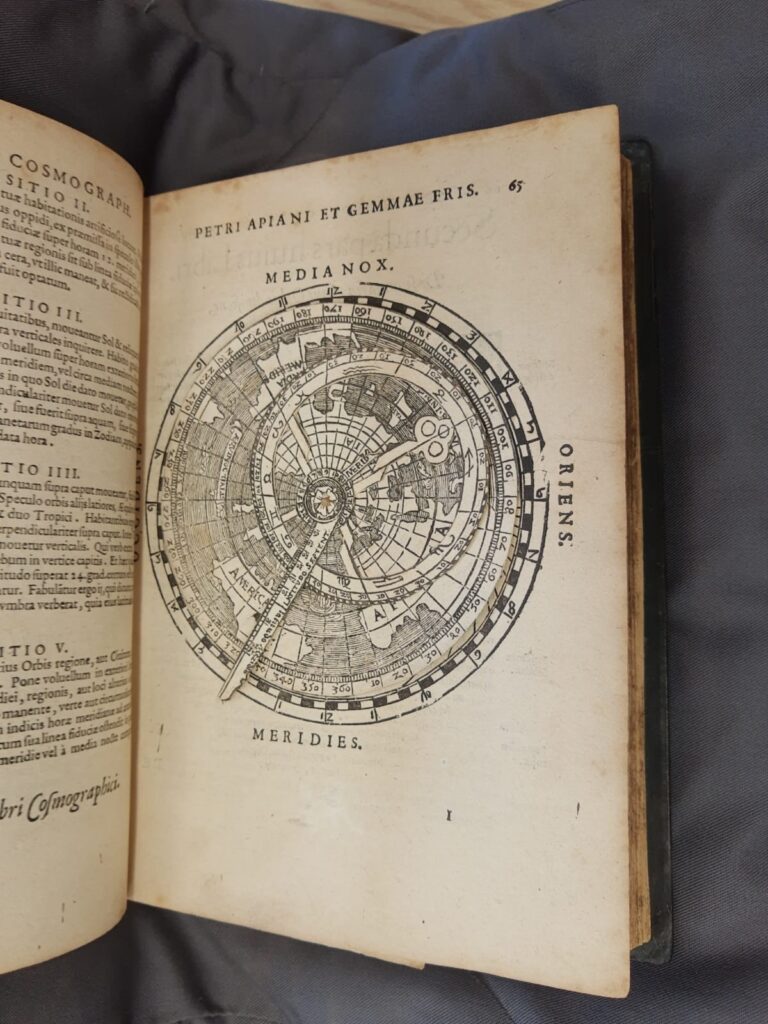

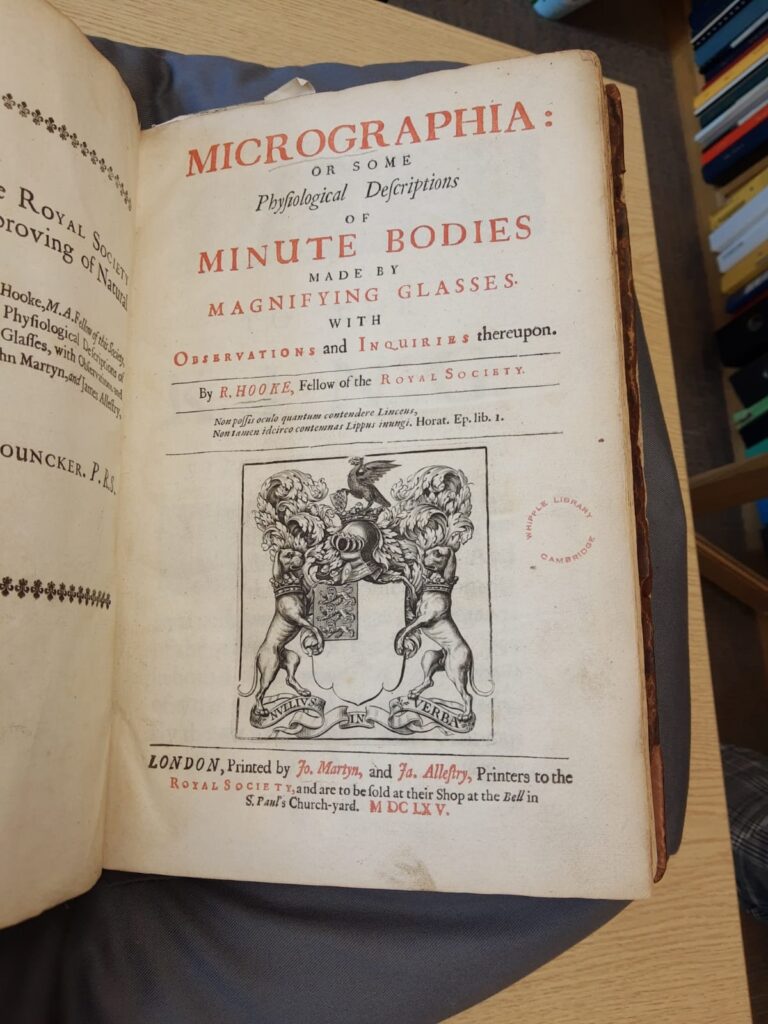

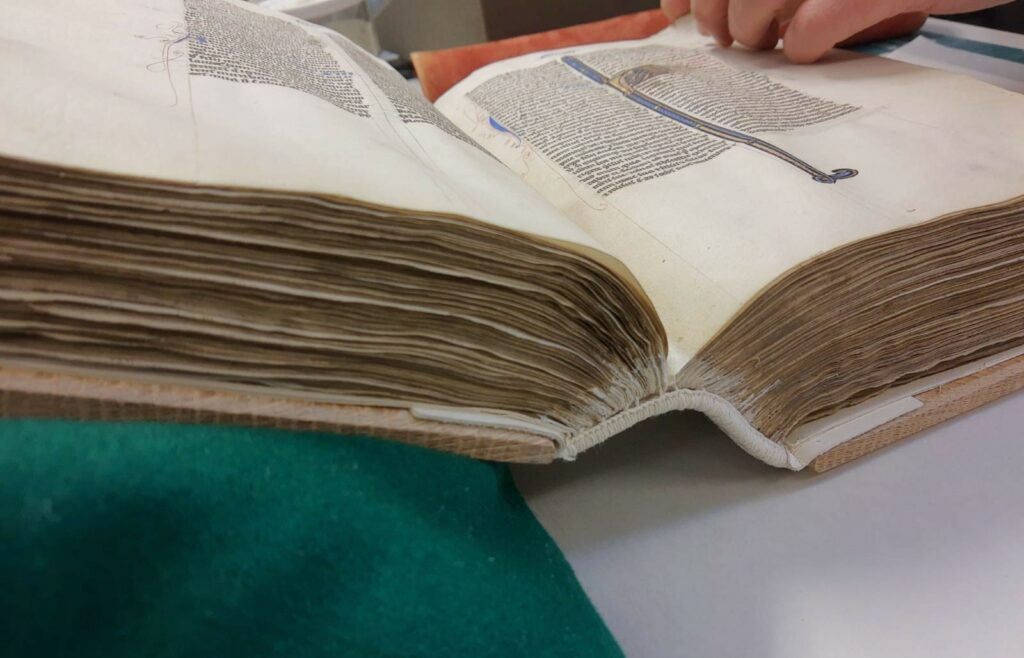

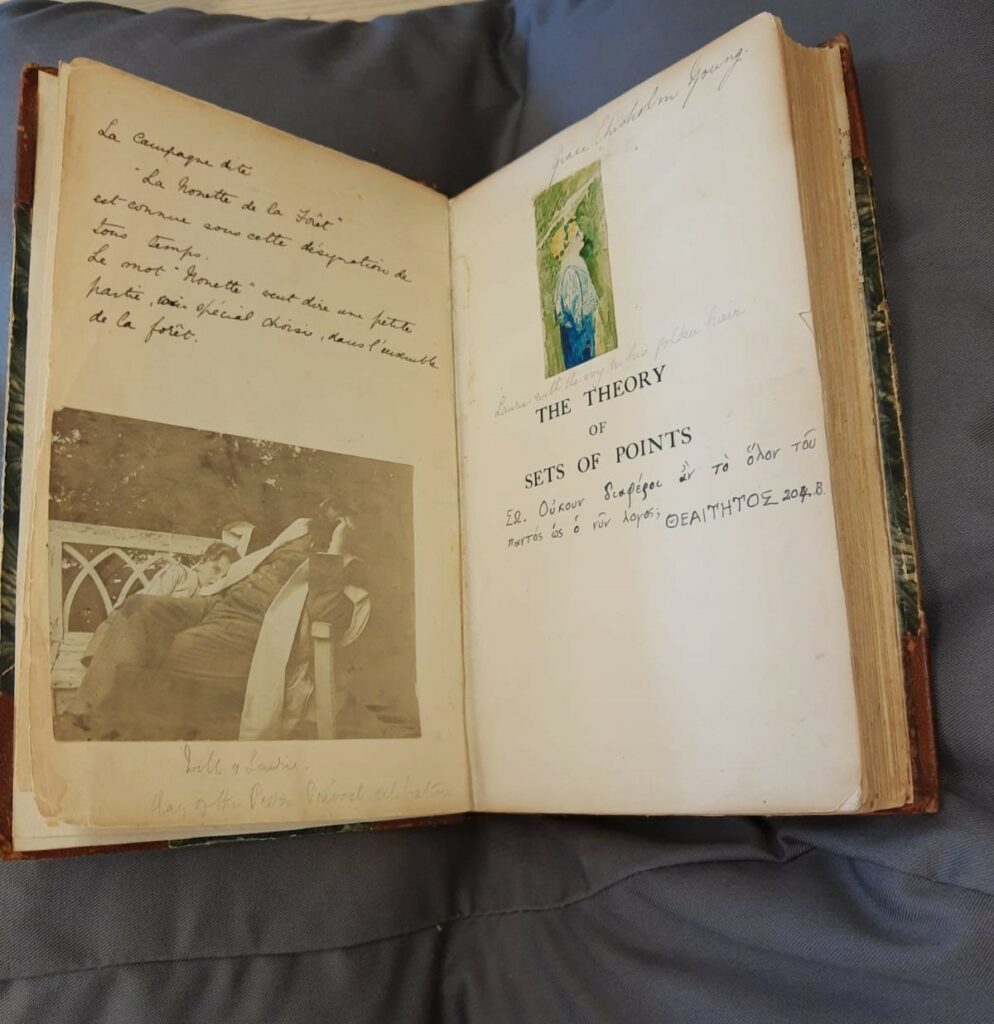

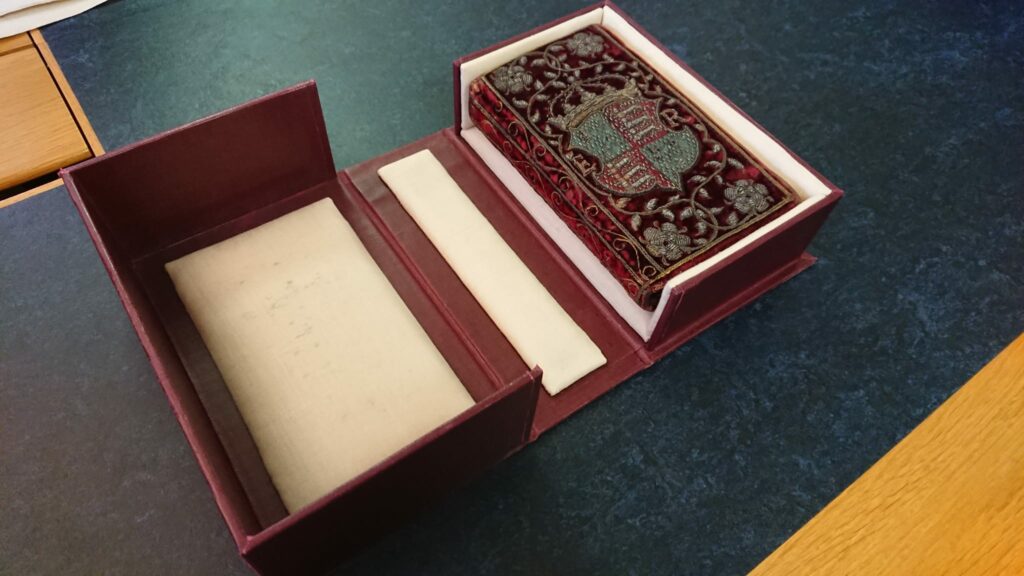

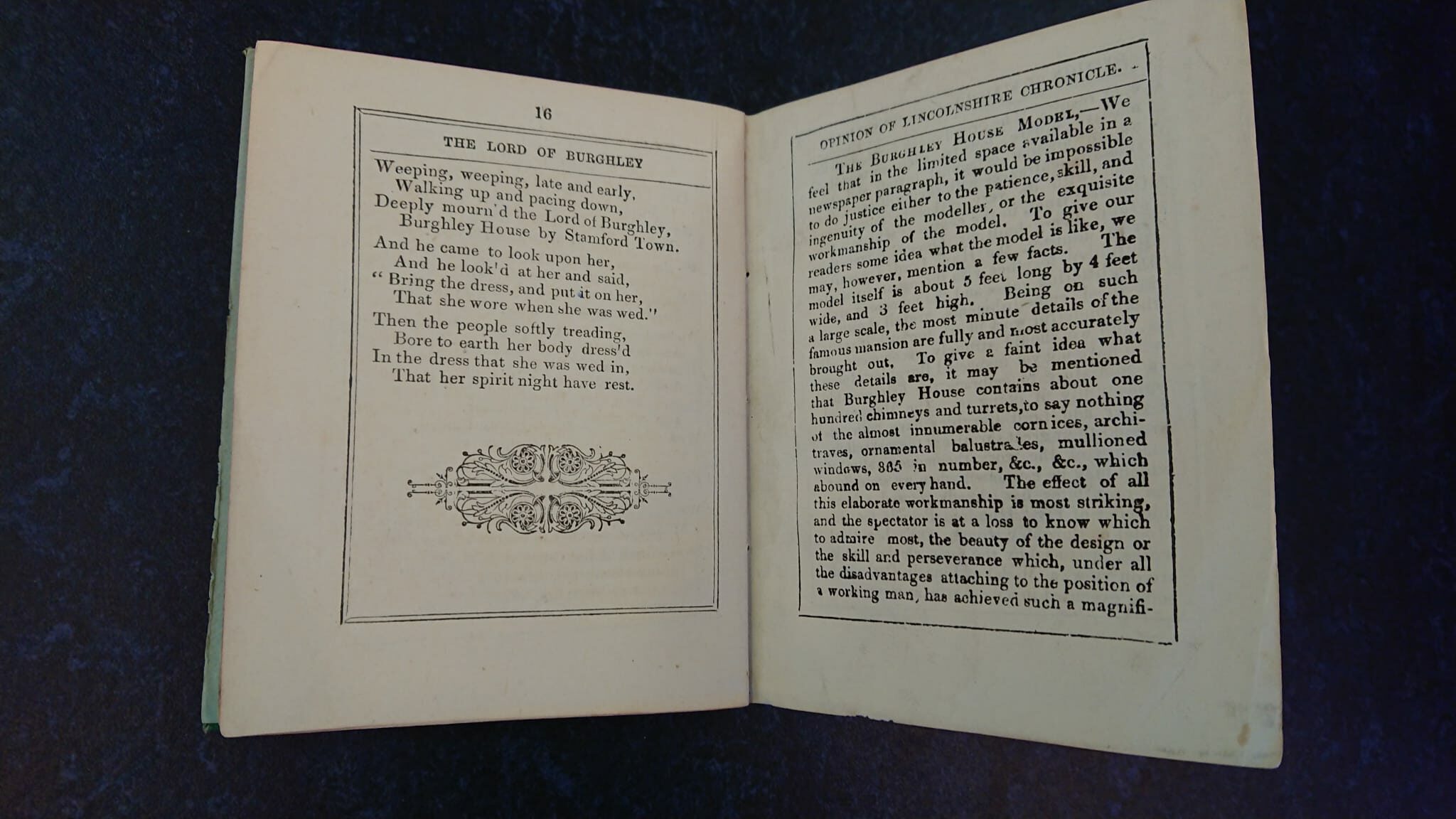

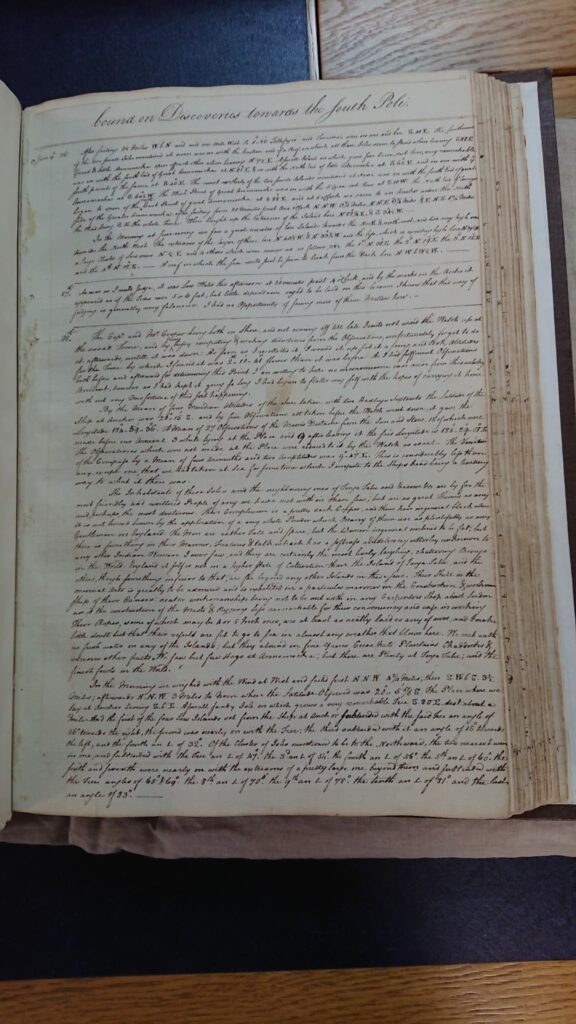

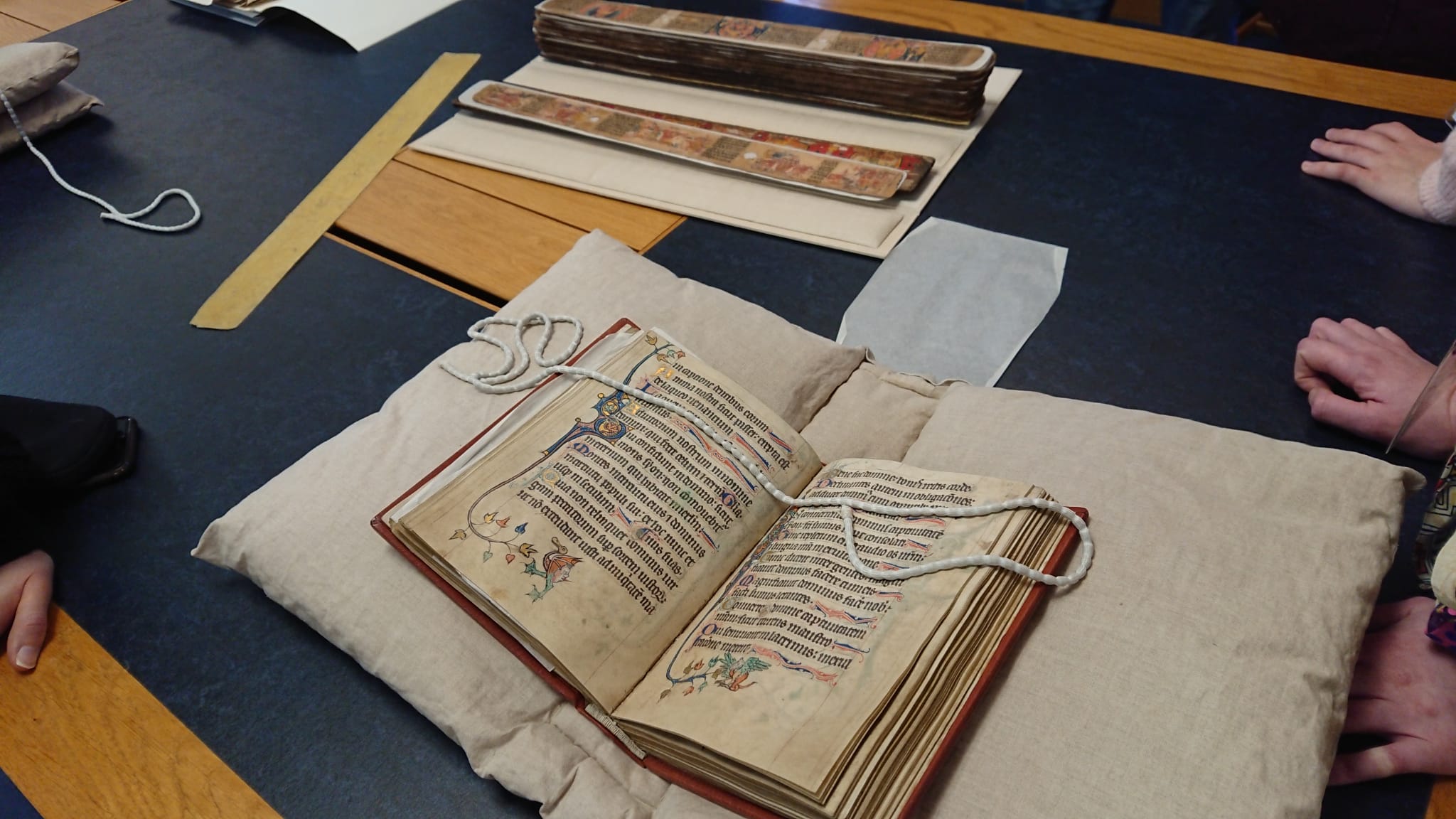

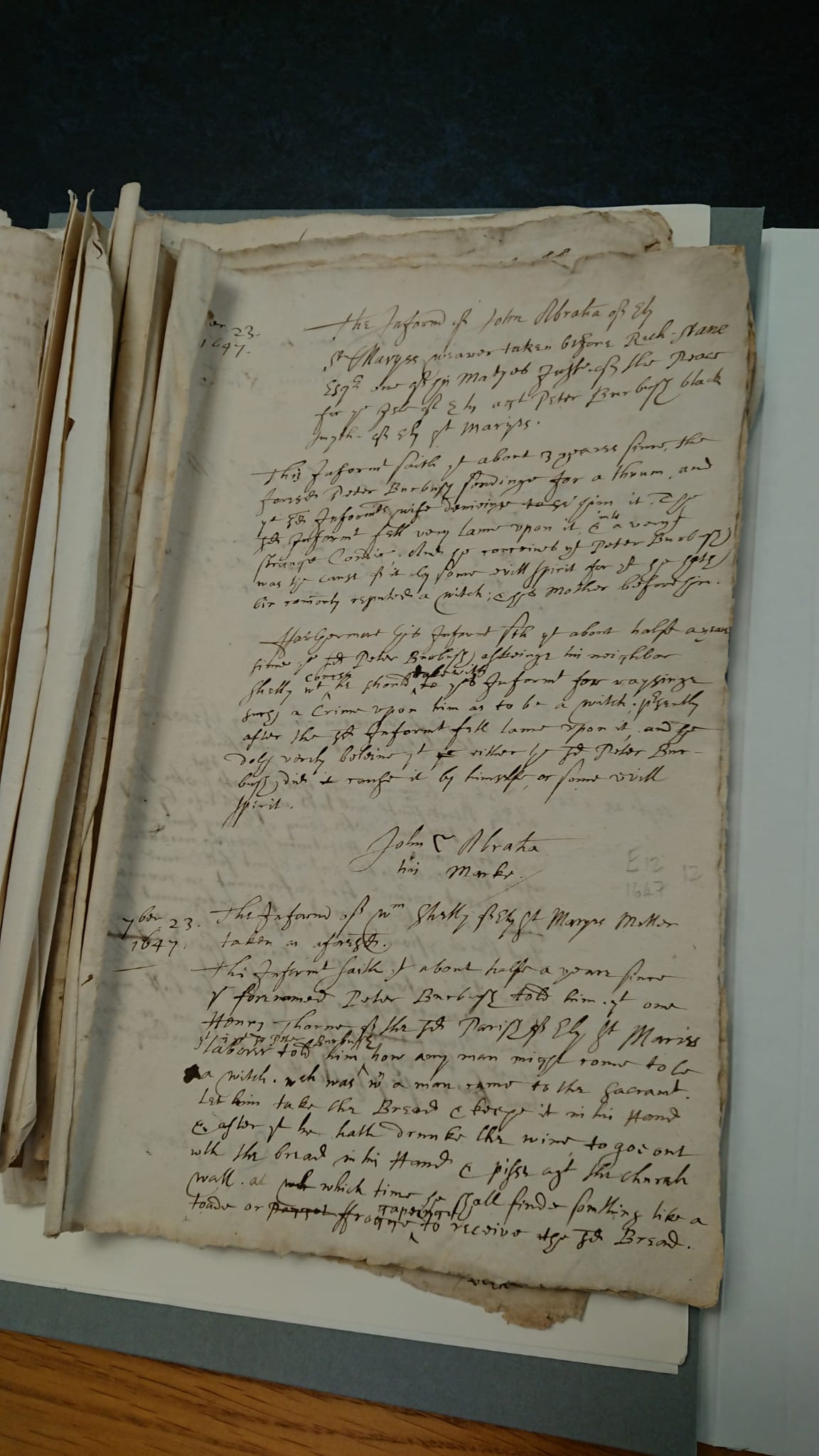

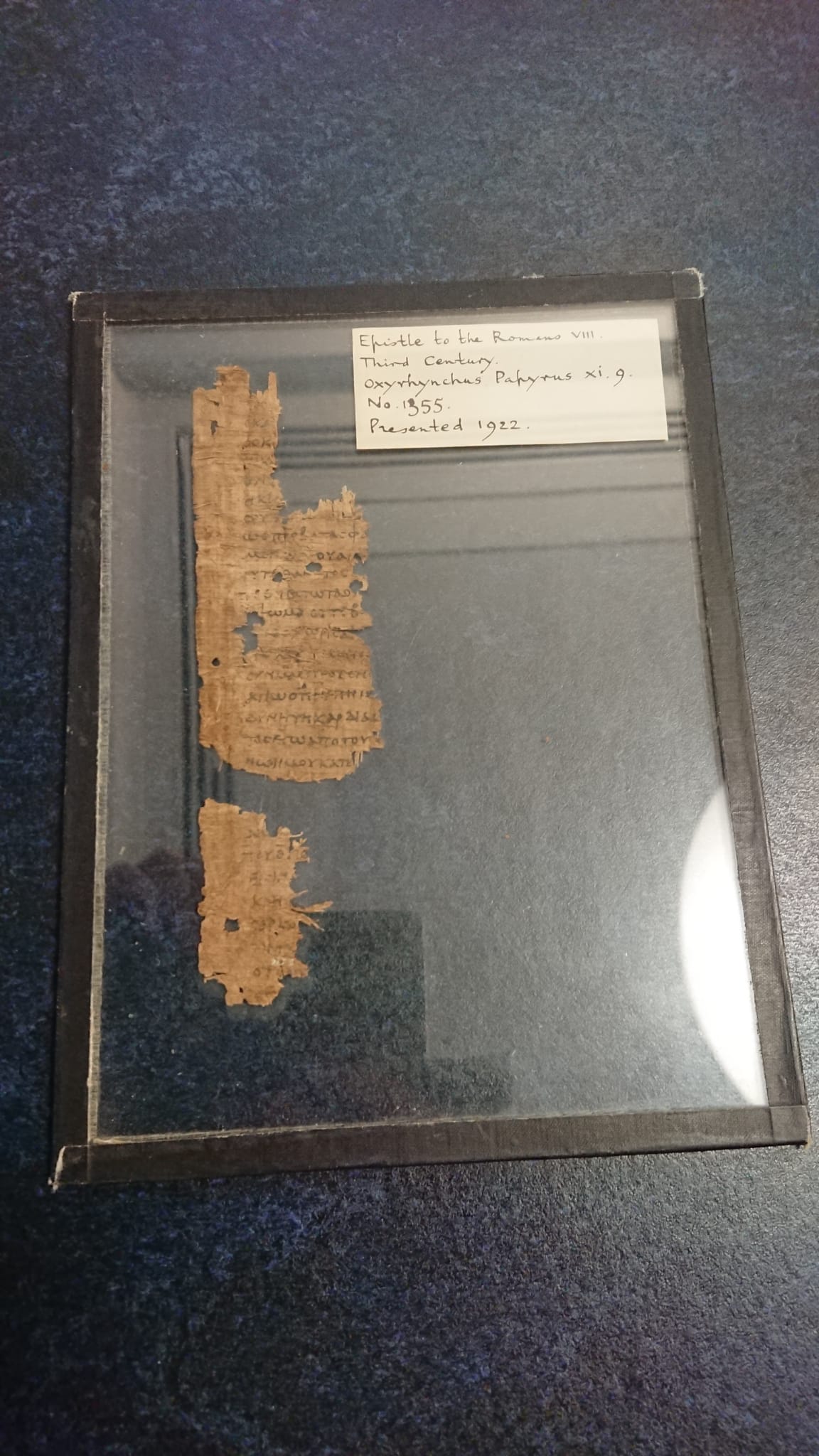

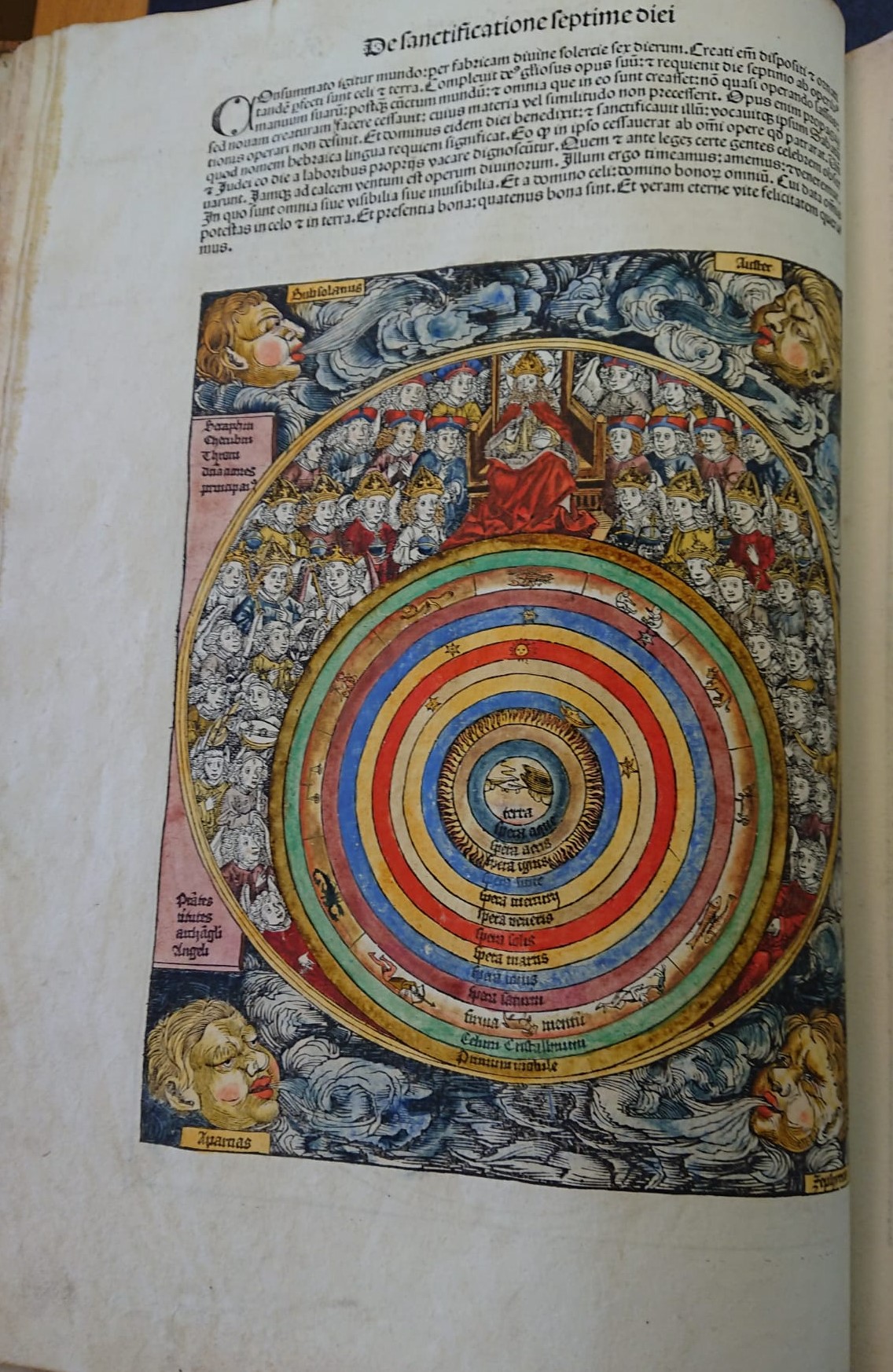

“One of my (many) highlights has been the time I have spent with special collections, whether that be my chats with experts in the library or while curating my small exhibition on early modern astronomy. There’s nothing like reading about an old book for ages and then getting to actually hold an original copy in your hands!

The biggest highlight of all, though, has been the people. I could not have asked for more of anything – be it support, expertise, or general brilliance – from the people I’ve met this year. They’re absolute stars and are a enormous part of what made my traineeship so wonderful.

Now that my traineeship has finished, I’m going on to work as a library assistant at another college. Alongside, I will also be doing some volunteer book cleaning of some sadly mouldy special collections. So I still get to touch old books – even if it’s through some lovely latex gloves!”

Katherine

“I have had an excellent time on my traineeship! I’ve really enjoyed involving the library in Outreach efforts, and my best achievement was putting together an archive exhibition for my college’s 150th anniversary on its Working Women’s Summer Schools. Weirdest moment was definitely finding lots of tiny plastic babies on the shelves (apparently it’s some kind of TikTok trend?). I’m pleased to say I’ll be continuing in college librarianship (though hopping across to a different library!) – lots of time still to explore interdisciplinary books and chat to students!”

Lucy

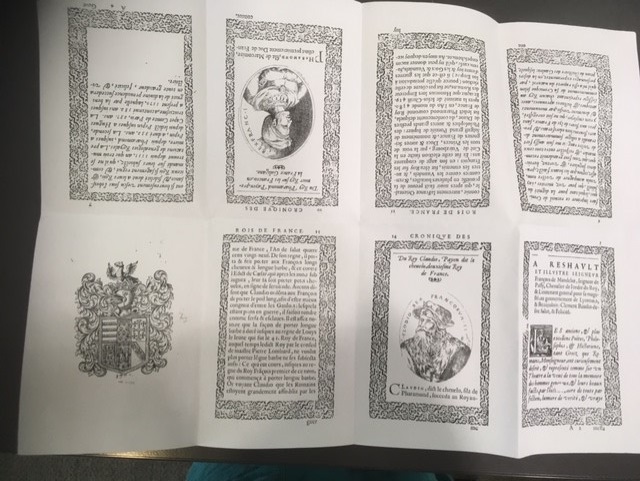

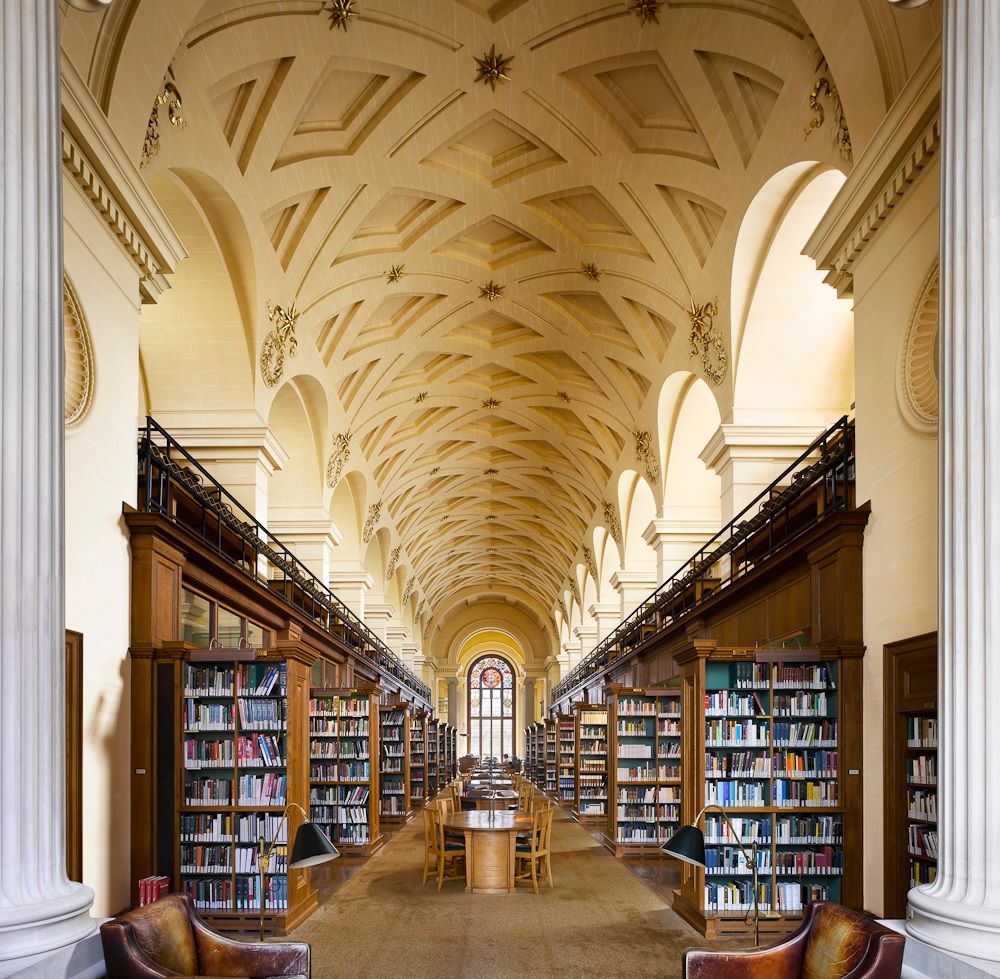

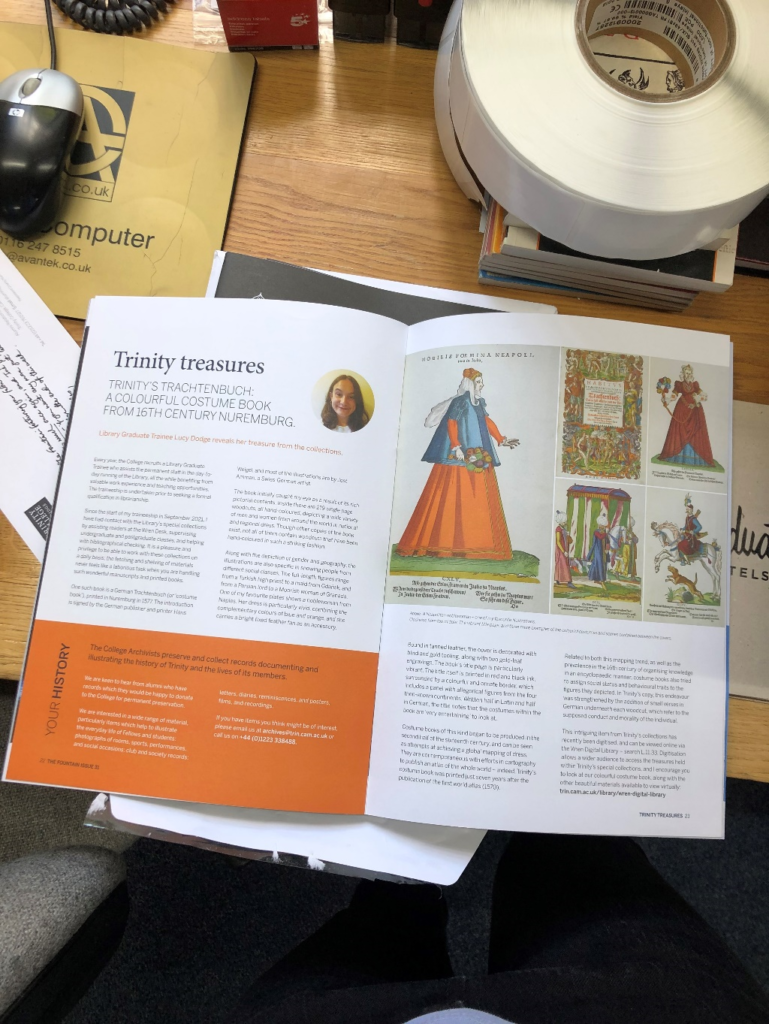

“A personal highlight has been working in the historic Wren Library every day, having close contact with the incredible and diverse special collections housed within its walls. Halfway through the year, I was given the opportunity to write an article for Trinity’s Alumni magazine about a ‘Trinity Treasure’. I chose a colourful costume book (‘Trachtenbuch’) from 16th century Nuremburg. It was a wonderful way to explore in more detail a book within the collection, learning about the context and history of its production. You can read the article here on pages 22-23.

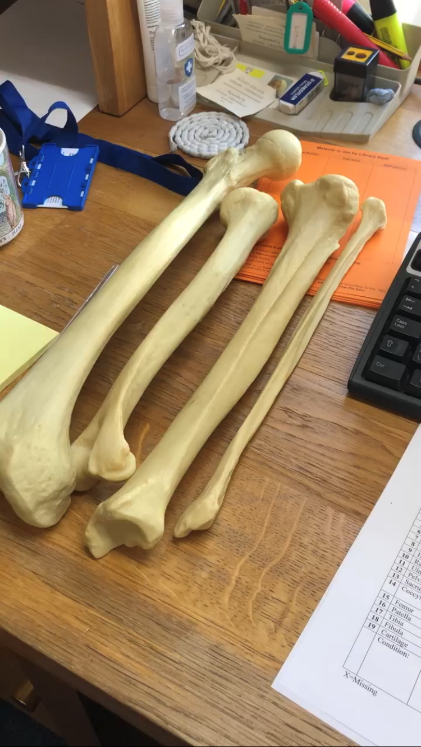

I also feel I should give a shout-out to one particularly weird and wonderful task I undertook – checking back in the skeleton models that are given to medical students at the start of the year. Sitting at my desk surrounded by fibulas, ulnas, clavicles, and sternums was a particularly bizarre experience. I am now far more well acquainted with the medical terms for human body parts – something that I wasn’t necessarily anticipating pre-starting at Trinity! The fact that each skeleton also has a name was a source of amusement – Cressida, Samson, Eve, and Gaspar are now safely back in their boxes waiting for October 2022 to come around.

In terms of next steps, the plan now is to move back to London – I am starting a new job at the Natural History Museum (as a Library and Archives Assistant) and will begin a two-year part-time Masters course in Library and Information Studies at University College London. I am incredibly sad to be leaving Trinity, and will really miss my work here, but am also excited to see what the future holds in store.”

William

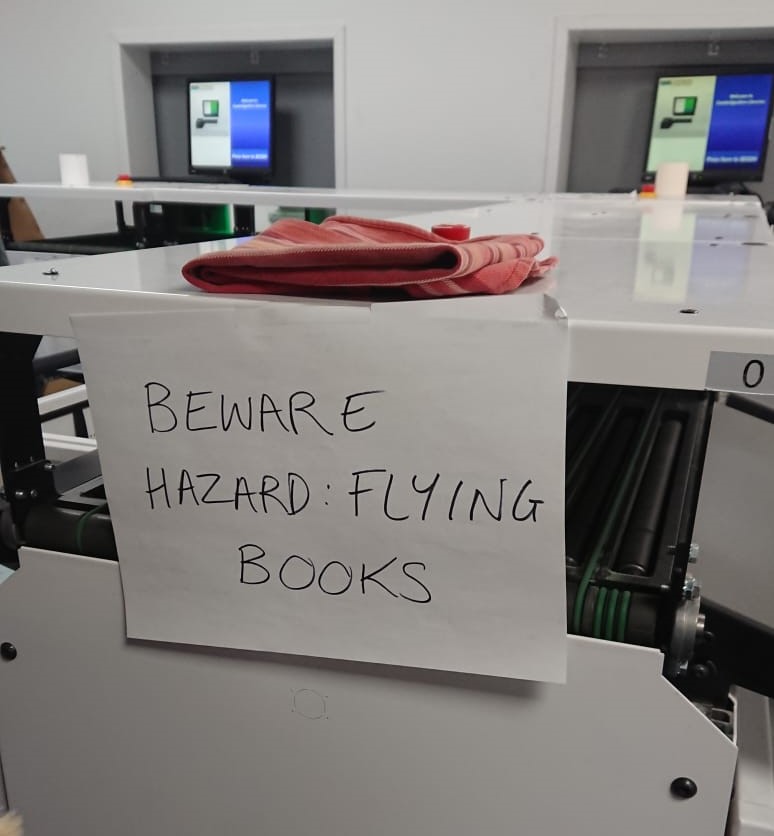

“I have really enjoyed my time as a Graduate Trainee Librarian. The opportunity to visit a wide variety of libraries and library-adjacent enterprises has broadened my understanding of what a librarian can do. I particularly enjoyed visiting the British Library and their enormous basements and amazing conveyor belt system for moving books around. (It felt like I was behind the scenes at Monsters, Inc!) However, my favourite aspect has been the camaraderie between the trainees, and I enjoyed meeting up with them both in and out of work.”

We would like to say thank you to all the amazing library staff who have supported us this year, and welcome to the new cohort of Graduate Trainees for 2022-23. We hope you get as much out of it as we did!