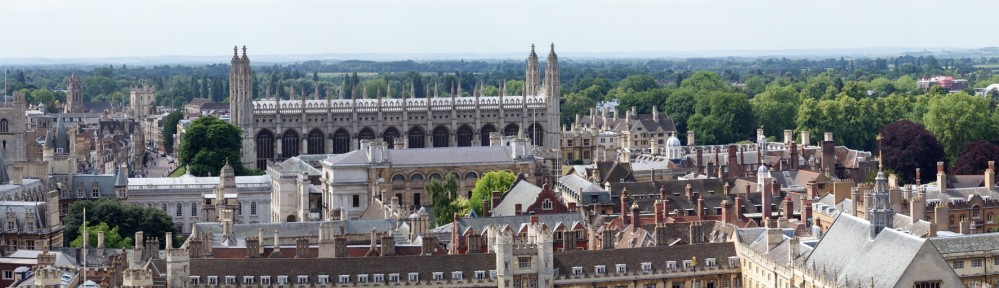

Outside of the (jam packed!) timetable of events, workshops and visits planned for the trainee librarians over the year of our traineeships, we are also encouraged to organise our own trips relating to our librarianship interests and our library training.

As an alumna of Clare College, I was very excited to hear that the Fellows’ Library at Clare was finally re-opening, after being out of operation for 5 years, with the collection being in specialist storage since 2018 as a part of building and refurbishment in Old Court. This closure spanned over my own three years as an undergraduate at Clare, so I never got to see or use the Fellow’s Library. So, I set about organising a trip for the trainees to visit Clare College and to have a tour of both the Fellows’ library and the student library across the way in Memorial Court. I also wanted to organise this trip in part because I owe the Forbes Mellon Library for my pursuit of librarianship; it was working there part-time in the summer of 2022 where I fell in love with librarianship (I was particularly a big fan of book covering and labelling – I love a cut and stick activity) and working there is also how I learnt about the Graduate Traineeships.

Forbes Mellon Library

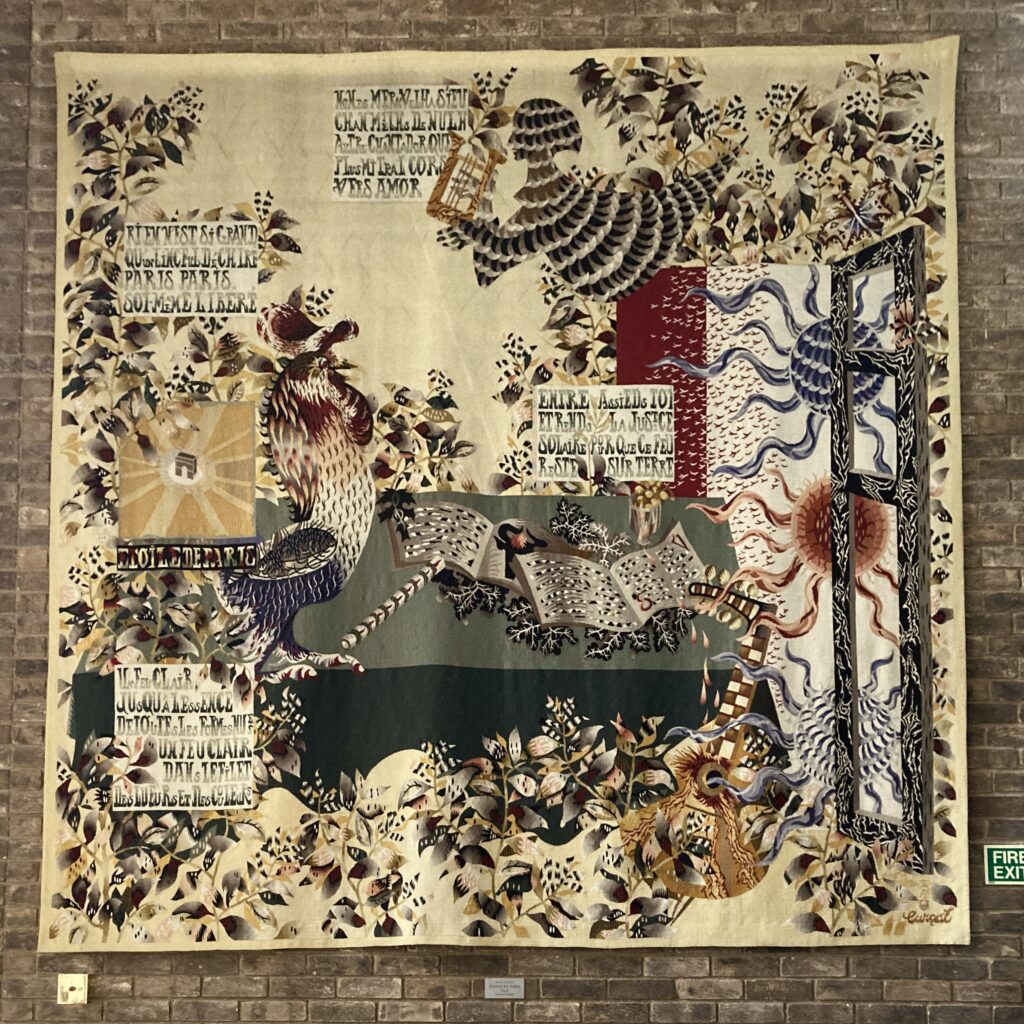

We began our trip congregating in Memorial Court on Queens’ Road, which hit me with a wave of nostalgia as I lived here for all three years of my degree. The Forbes Mellon Library (FML) was our first stop; located in the heart of Memorial Court, the FML was constructed in 1986, to accommodate the growing number of undergraduates studying at the college. On entering the building, the librarian pointed out a series of portraits of women Fellows hanging on the balcony, which houses the closed-access shelves of the library. A particular favourite of the group was a portrait featuring a plush frog. She explained that these were part of a series of celebrations in the college commemorating the 50th anniversary of the changing of statutes to include women among the students and Fellowship, making Clare the first Cambridge college to have co-education in 1972. Another artistic feature of the college, a statue entitled HOMMAGE, which stands between the Forbes Mellon Library and the University Library, was also acquired as part of the 50th anniversary.

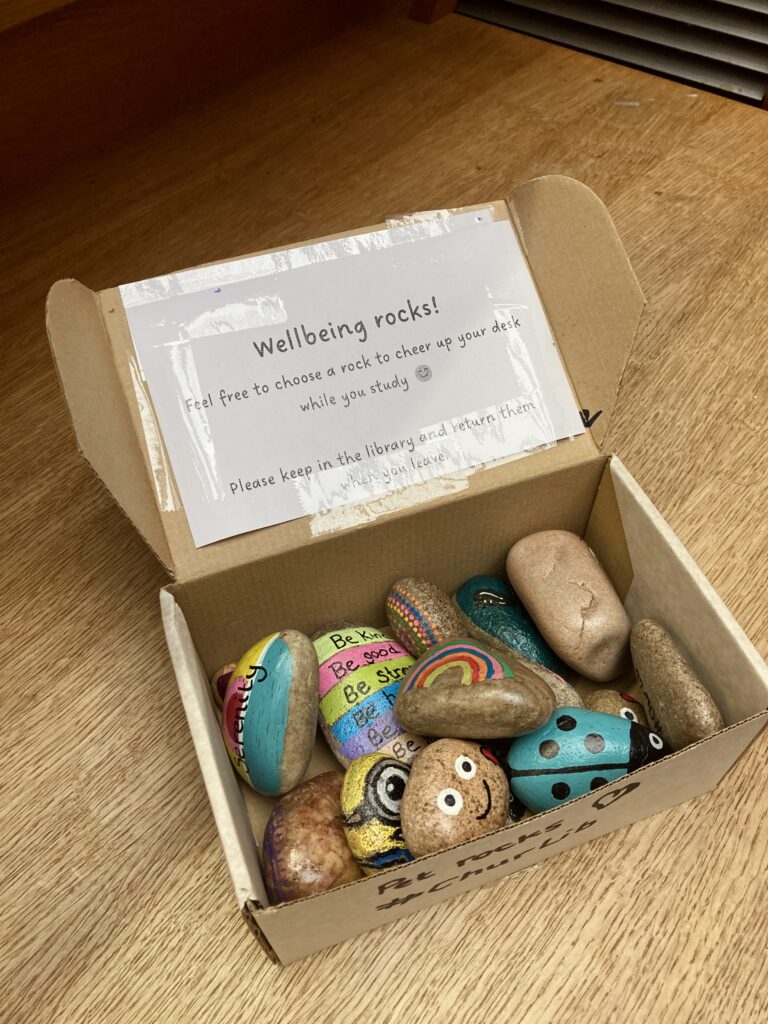

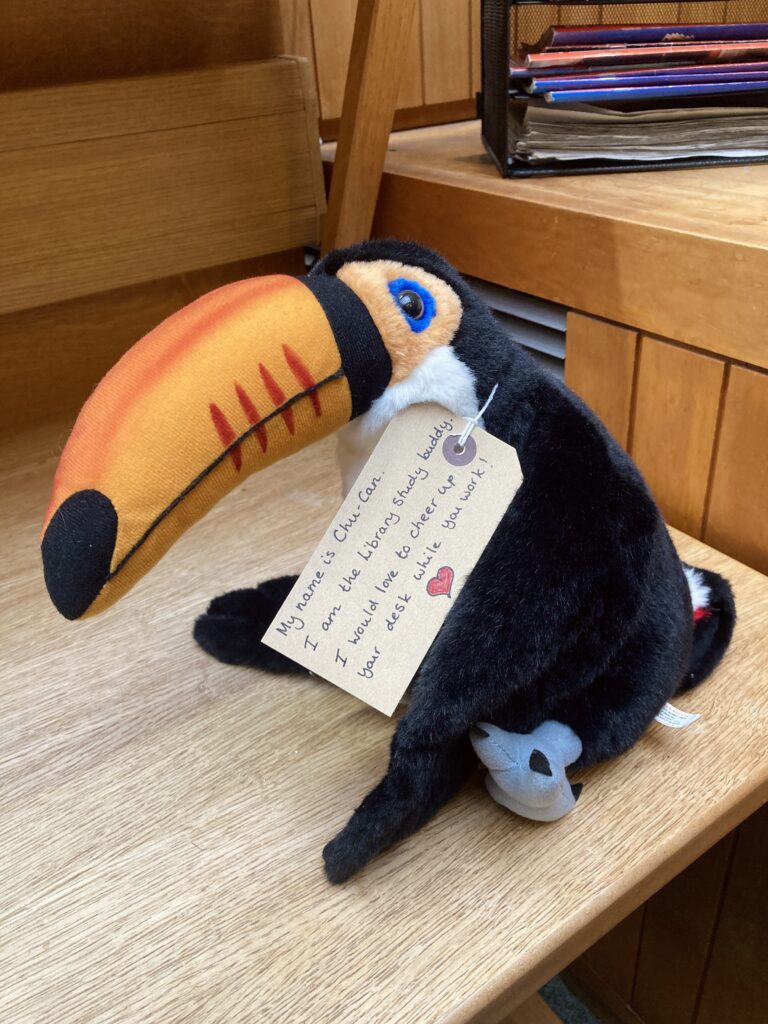

It was also explained that this library has a rather rare feature; it shares a building with several music practice rooms! This is an interesting combination, given the unique silence of library spaces… but surprisingly one that works in nice harmony, with very few disturbances occurring. There is also a Library Common room located in the building, which is highly frequented by students, which serves as a relaxed area to study or take a break. This space is harmoniously run by the Union of Clare Students and the library team, with calming colouring books, a casual reading selection (borrowable on trust), and free hot drinks and biscuits available. One of the projects I worked on while working there was to weed this collection, to keep it updated and relevant for the students.

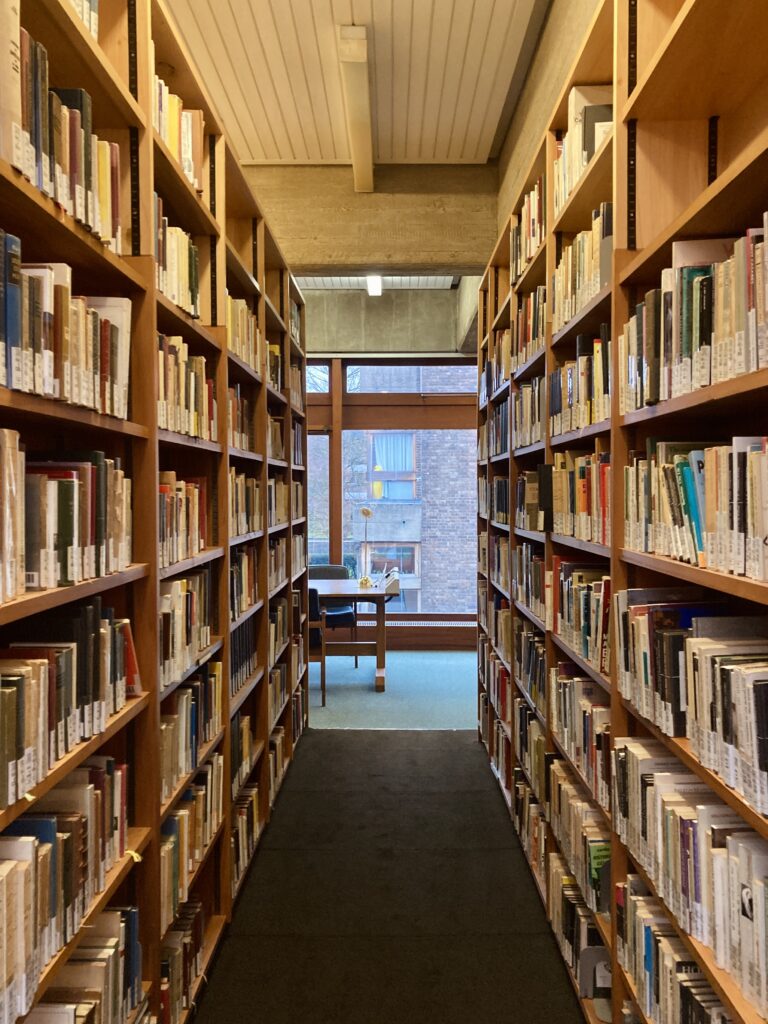

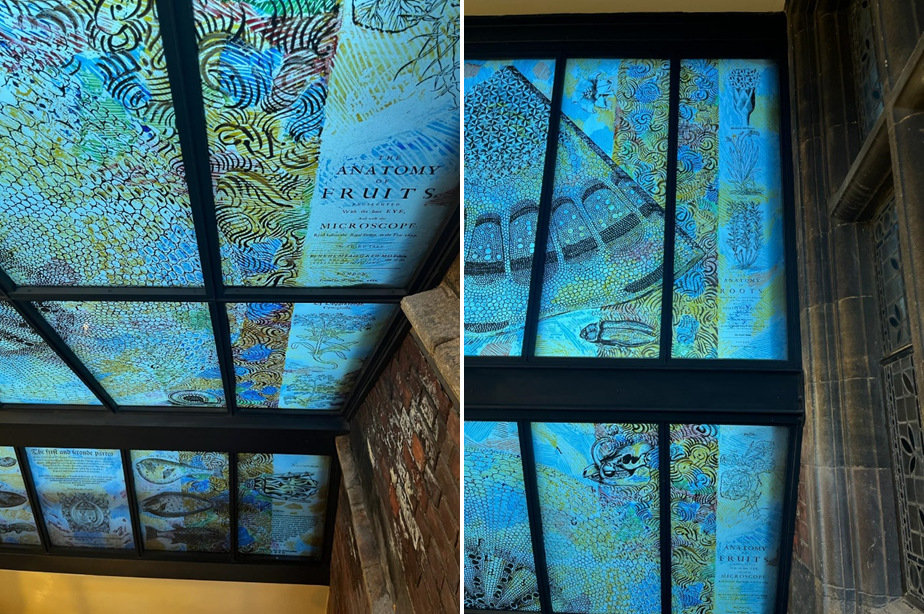

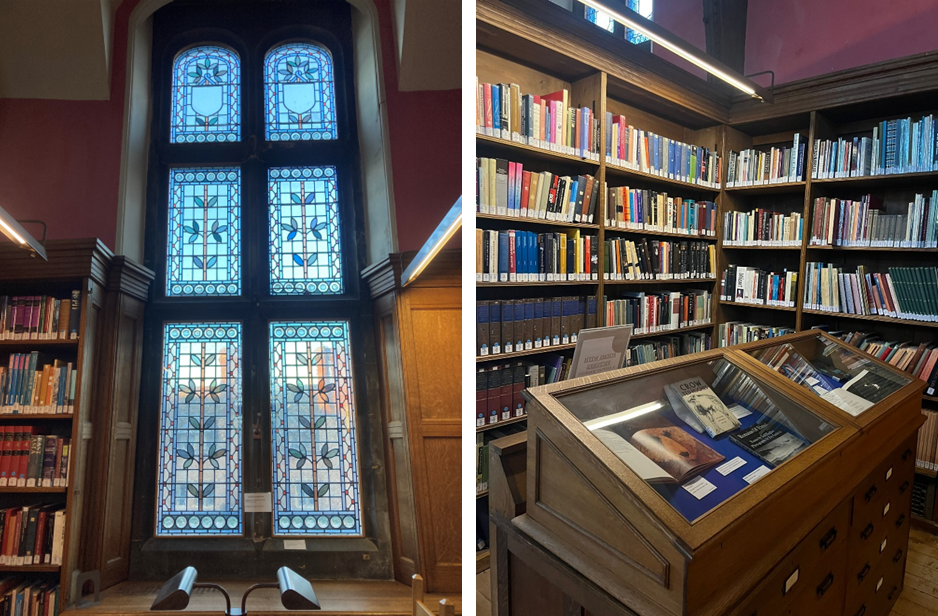

Entering the main library itself, we first saw the display table which is located directly in front of you as you enter the building, where a brand-new display was set up, featuring books, DVD’s and other items from the collection relating to women’s history month. On our way to a side room that contains the printer and monitors, as well as housing the welfare and academic collections, we walked past a station full of equipment free for students to use, from staplers to whiteboards. There was some interest amongst the group as to how the items were picked, and whether the Clare students seemed to find them useful. We were then led up to the first floor, where we could fully appreciate the beautiful shelving that runs along the walls of the hexagonal building, with their huge bay windows filling the library with light (many an essay of mine was written on one of these window seats, so apologise if I am a little biased about their loveliness). The librarian also explained how they had been working on a reclassification project recently on their history collection; you can read more about reclassification and its role in library decolonisation projects in Liz’s blog here.

Law Reading Rooms

We then filed out of the Forbes Mellon, and turned into one of the staircases, where the college archives were pointed out to us. Here we visited the two Law Reading Rooms, (the Lipstein and Turpin rooms) which both law and land economy students in the college have access to, with the Turpin room also having a computer room. These rooms have their own library collection, for reference only. As with most of the windows in the library, and in Memorial Court generally, the University Library is ever-present. A particular selling-point of Clare is just how close the libraries are, with Sidgwick site also being just a couple minutes away. The librarian explained how this close proximity also helps them to facilitate access to the books their students need.

Fellows’ Library

Making our way across the road and through Clare Old Court, with spring flowers blooming beautifully along the walkway, we briefly stopped on Clare Bridge where I pointed out one of my personal favourite features of the college – The Wedge – which, like many old-Cambridge things, has several combating mythologise surrounding it, all more absurd than the last. On the way to the Old Library we passed the newly refurbished Old Hall, and also a Medieval Chest. Several colleges with Old Libraries have chests such as this, which at one point would have functioned much like a library in that they stored key documents of the college, in fact this chest specifically is referred to anecdotally as the “earliest library of the College” and is roughly dated to the fifteenth century. We were then led through the senior common room to reach the Library; this placement of the library, between the Masters’ Lodge and SCR, and accessible from either side, is indicative of the central role the library has historically had in Clare.

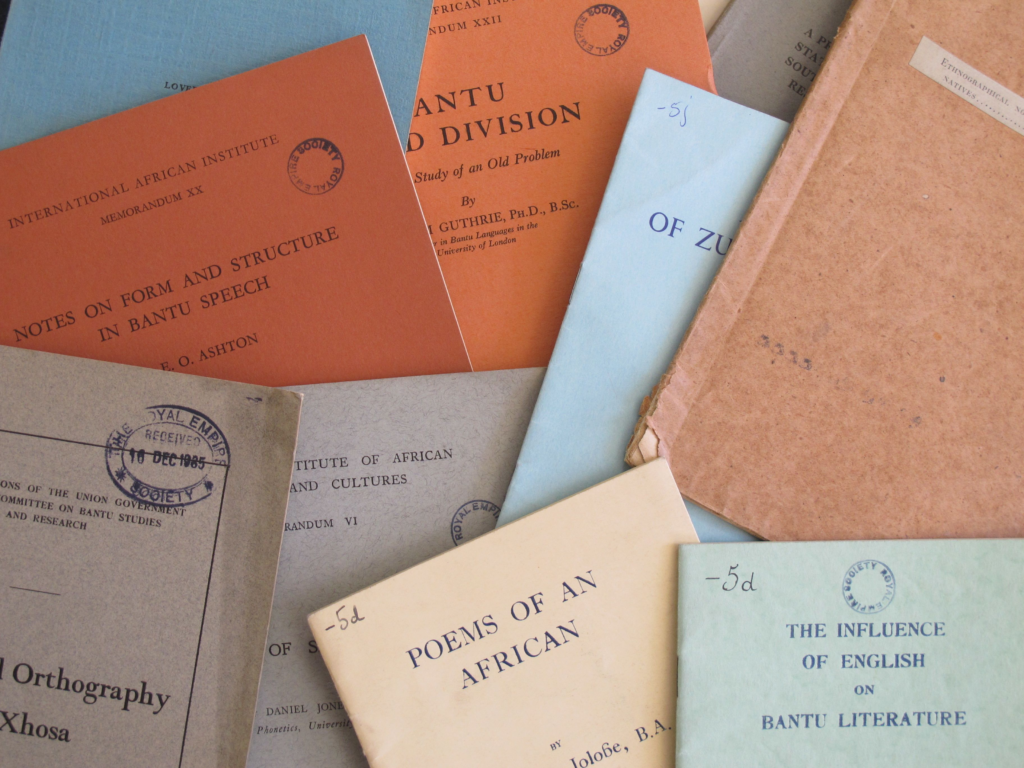

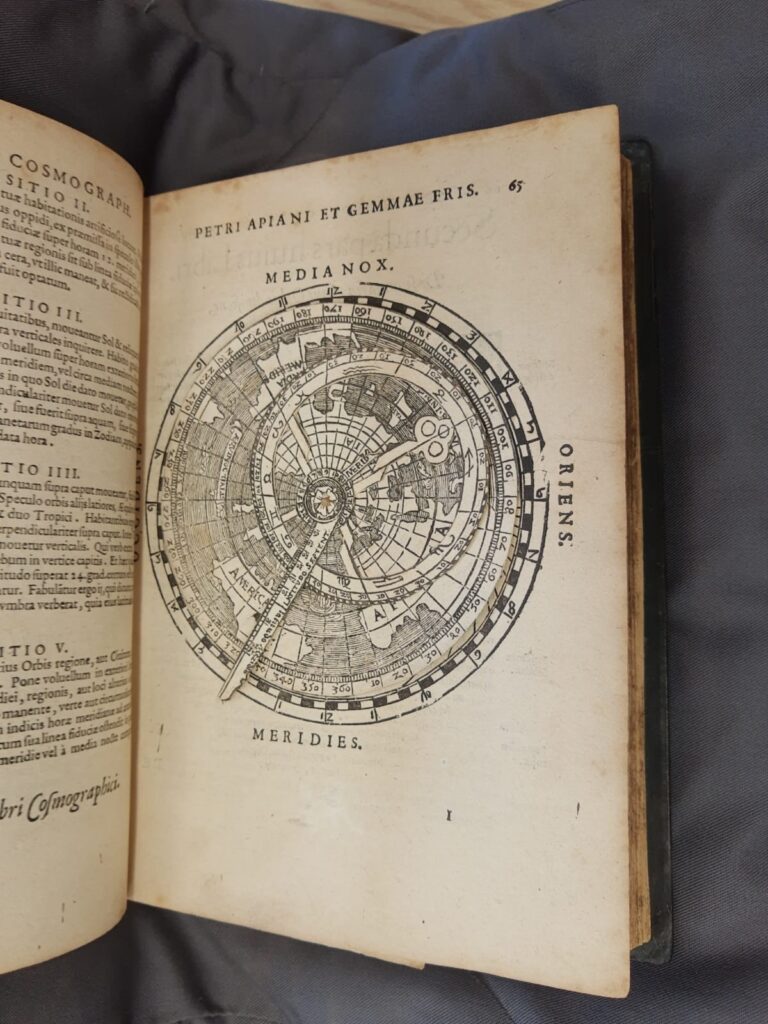

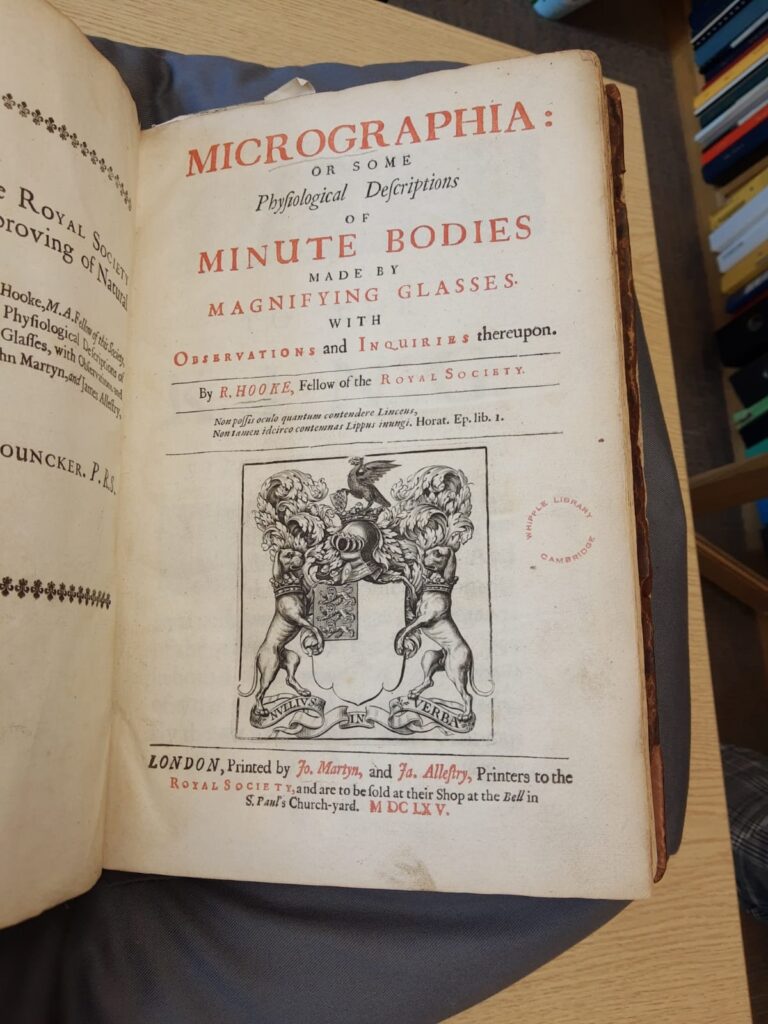

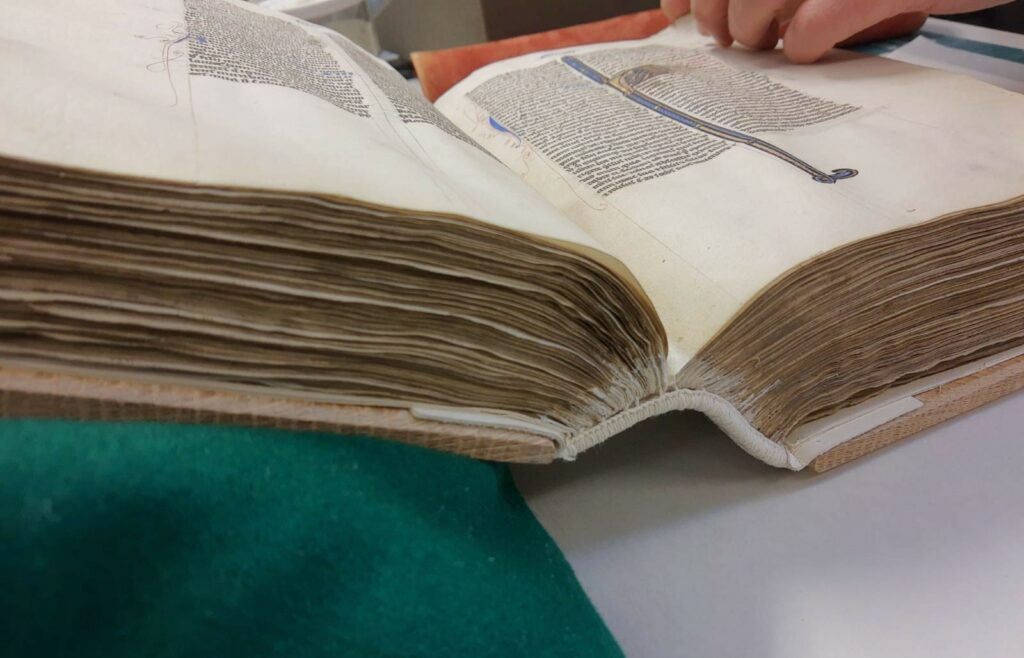

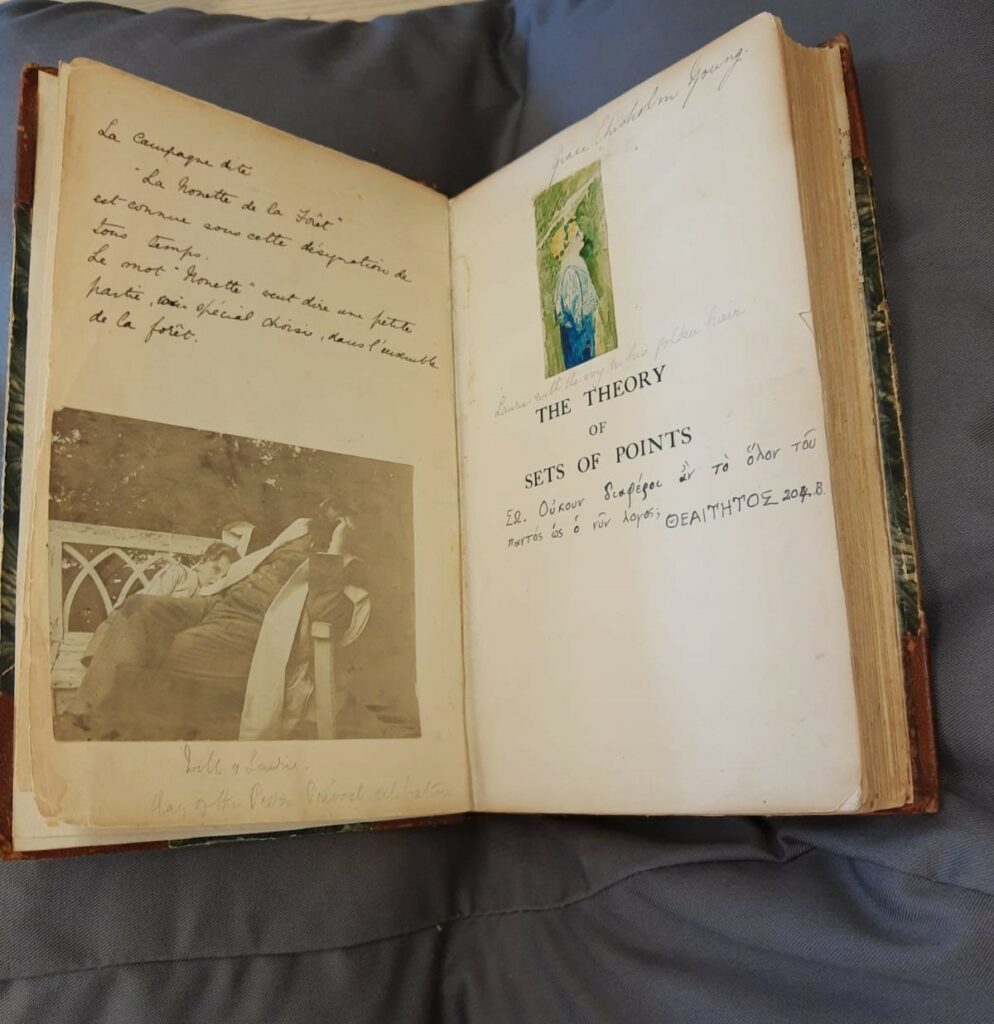

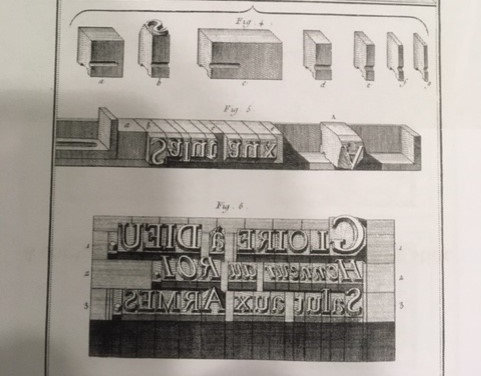

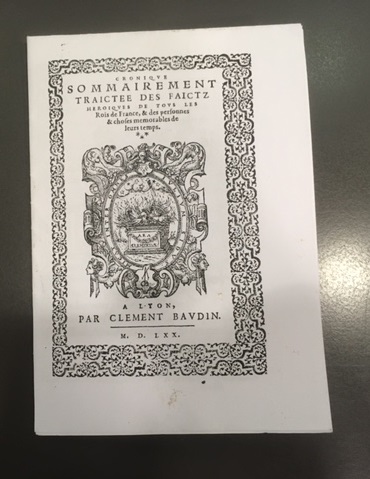

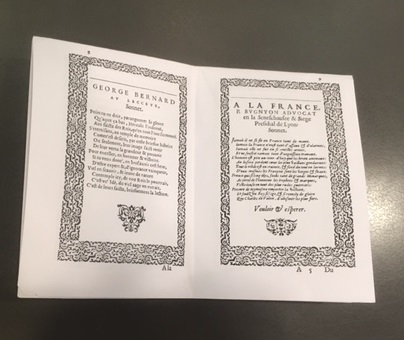

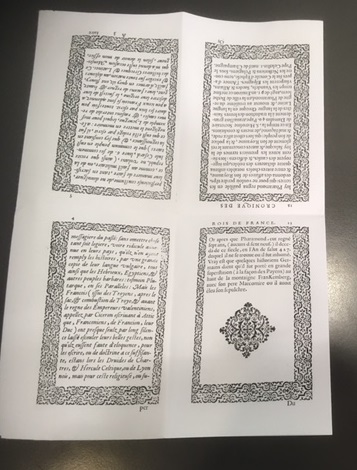

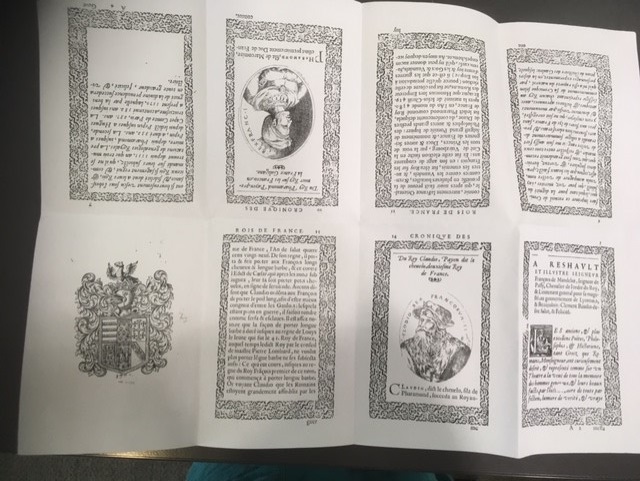

On entering the Fellows’ Library, we met with the Assistant Librarian who had kindly laid out a selection of the collection for us to look at. This included highlights such as Cassius Dio of Bythynia (1592), edited by Henri Estienne, which came to the library from Master Charles Morgan (1678-1736, Master 1726-1736), and which is still in its original late-16th century binding, with fragments of a Hebrew manuscript. Both the Clare librarians and many of the graduate trainees had been to the 2023 Sandars Lectures, which were on Cambridge University bindings, so we had particular interest in three Cambridge bindings from the collection, two of which are believed to be from the workshops of early Cambridge binders John Siberch and Nicholas Spierineck, and one which showcased a pink covering!

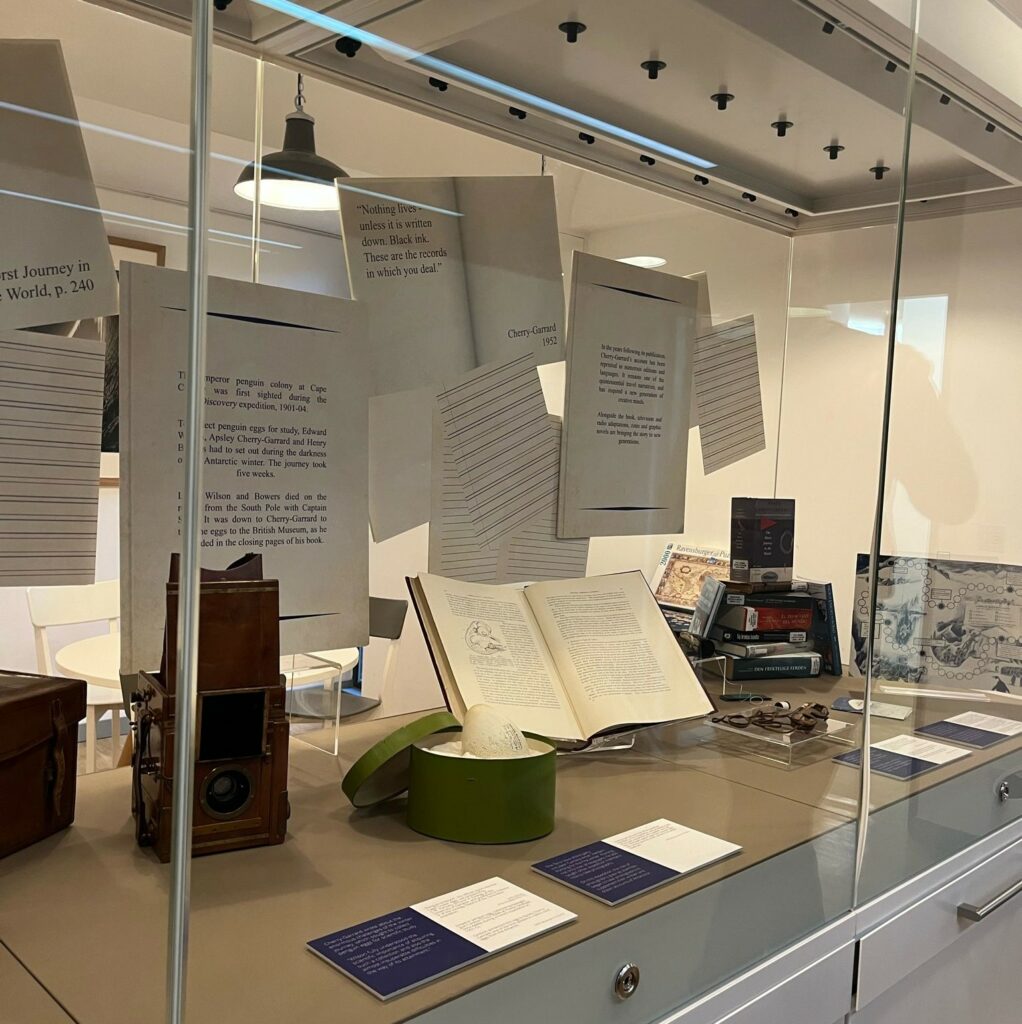

Alongside this, we also had the opportunity to meander around the exhibition in the Fellows’ Library which was curated by the Fellows’ Librarian, Prof. Tim Chesters, which featured selections from the collection on the theme of “America”. We also heard about the (somewhat tumultuous) history of libraries in the college, including a presumed fire which sadly caused the loss of much of the earliest part of the collection, as well as learning about the process of moving the books to specialised storage, working with the collection while it was in storage, and the process of having it all returned to college. It was fascinating to hear about movement of rare books on this scale.

River Café

We finished the trip in the new extension of the college – the River Room Café – which still had views of the University Library through its windows. We were kindly treated to a hot drink while we chatted to the Clare library team about their own experiences as trainees and their careers as well as our own plans and goals. The Clare librarians were very kind, receptive and welcoming to us visiting, for which we are very grateful, and I want to personally thank them, for teaching me the foundations from which I am developing my librarianship practice in my traineeship, for nurturing my love of libraries, and for running a wonderful library for Clare students.