Following on from Zia’s post below, the third library we visited on our jam-packed London trip was the National Poetry Library (NPL), located in the Southbank Centre.

After a spot of lunch and a short stop at Foyles bookshop on the Southbank (a necessary addition to the perfect day out for trainee librarians!), we eventually figured out which entrance to the Southbank Centre we needed to enter, and ascended to the 5th floor for the NPL. Despite the Southbank Centre being a haven of artistic venues, we were still all startled by the acapella singing in the lift, where a recorded harmony accompanies you throughout the ascent and descent and sings the floor you arrive at – the pitch higher or lower depending on which floor you wanted. It was certainly a unique introduction to the different creative space the NPL is situated in!

Just outside the main entrance to the NPL is the Little Library, a small area for children which holds a collection of books donated by the Swedish embassy. This welcoming little space provides an easily accessible area outside the main library where parents and children can explore poetry without having to enter the library proper.

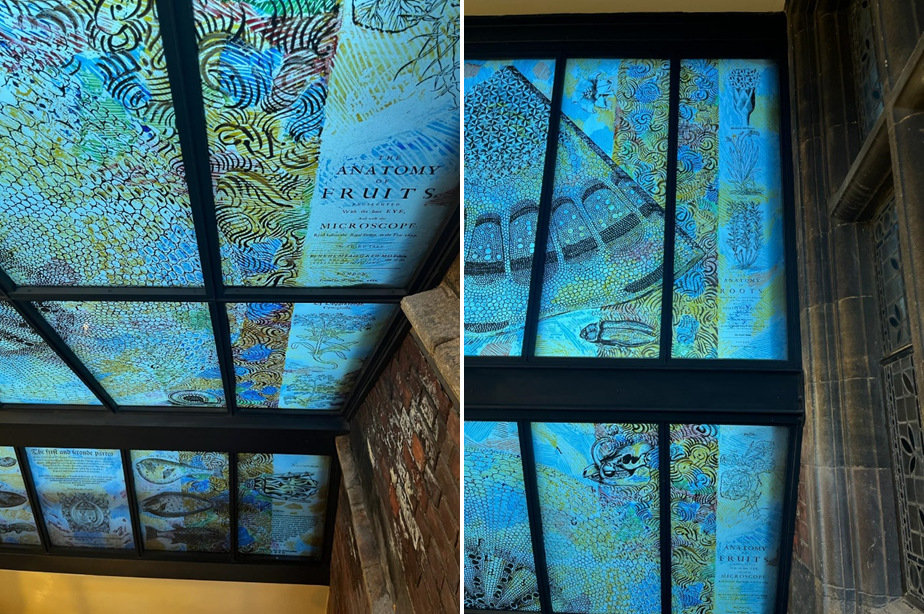

After being welcomed into the main library by the friendly team, we were introduced to the history of the NPL and its collection. The library was founded by the Arts Council in 1953 and opened by poets T. S. Eliot and Herbert Read. From the beginning the library offered a unique collection, stocking poetry published from 1912 onwards, with the aim to collect every poetry book published in the UK since then. The librarian explained how 1912 was a key time for modern poetry, with the first issue of the seminal magazine Poetry being published in Chicago, as well as a number of poems which began and contributed towards the Imagism movement. By 1988, the library’s collection had grown so large that they moved to their current location in the Southbank Centre.

The NPL’s ethos is to make poetry accessible to as many people as possible, with an especial focus on introducing young people to the diversity of modern poetry and nurturing their curiosity towards the different ways language and form can be experimented with. Anyone can join the library, and members can both browse the reference selection and borrow books from the lending collection. The library runs numerous other initiatives and events to get people involved and interested in modern poetry, including holding exhibitions throughout the year, often displaying unique ways poetry can be engaged with. For instance, a recent exhibit on poetry games included video games and poetry Jenga. They also host poetry readings in the library, as well as a series called ‘Special Editions’, where people can organise events to be held in the library, usually around a theme. On top of this, they hold a ‘Rug Rhymes’ poetry session for kids – we were told this event had become so popular that the library had to start ticketing it, as there were too many people attending for the space! Outreach to school groups also helps encourage young people to enjoy the collection, with the library prioritising engagement with local schools, highlighting how they are a library not just for the nation, but for the local community as well.

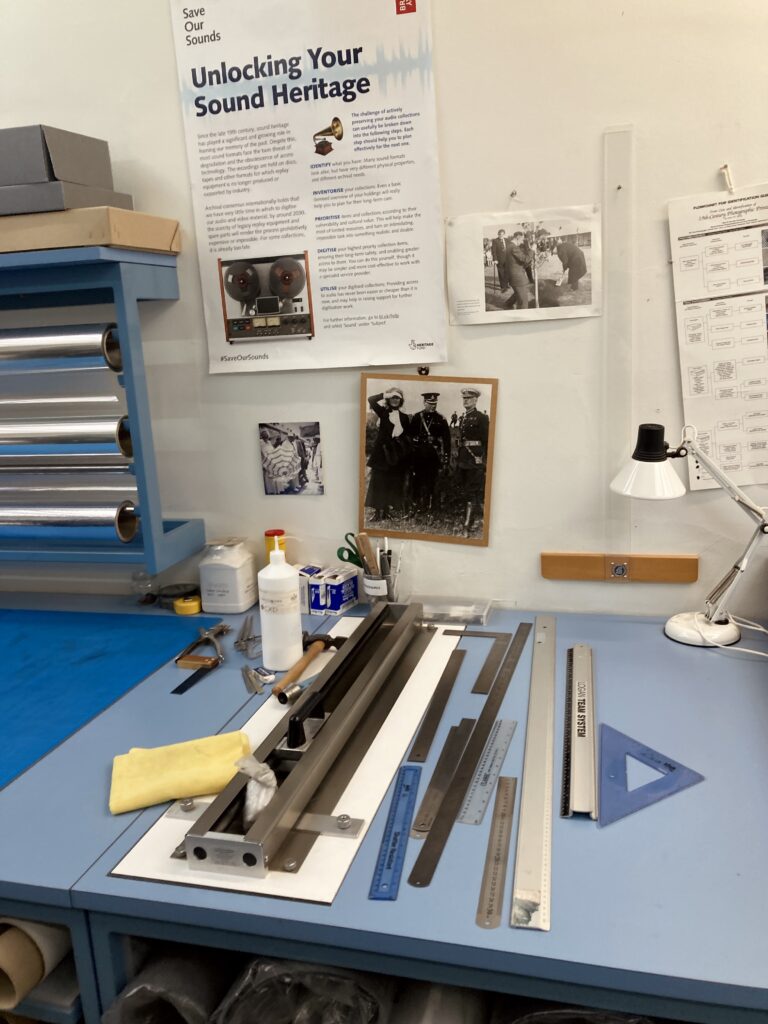

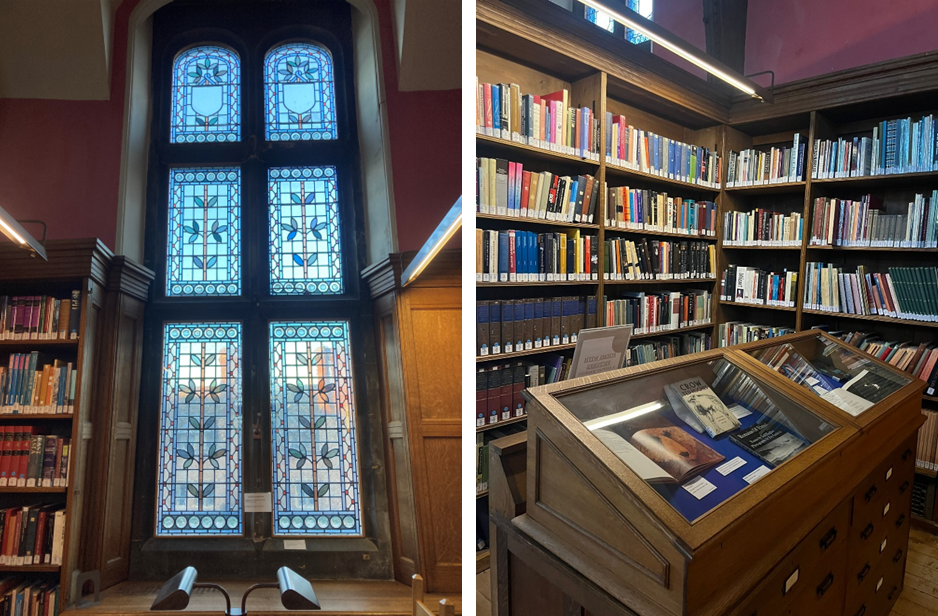

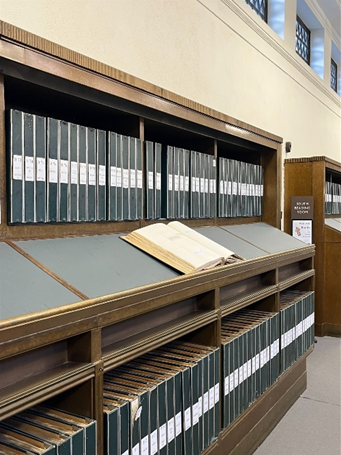

We were next shown around the library’s diverse collection, which expands far beyond poetry books! The librarian first showed us the Sound section, which is composed of a collection of vinyl and cassettes featuring poets reading their own works – these date back to the 60s and 70s, but also include some more modern records. As well as a large Sound section, the library also has special areas for kid’s poetry books, and also for poetry in accessible formats, like braille. The NPL also offers e-loans of poetry books if members can’t reach the library, as well as access to digital magazines.

At the heart of the collection are the magazines, which range from current issues of literary journals and well-known poetry magazines, to lots of small press publications. This collection is very popular, allowing readers to discover new poets and keep up to date with developments in poetry, in addition to helping aspiring poets find the best publications for their own work.

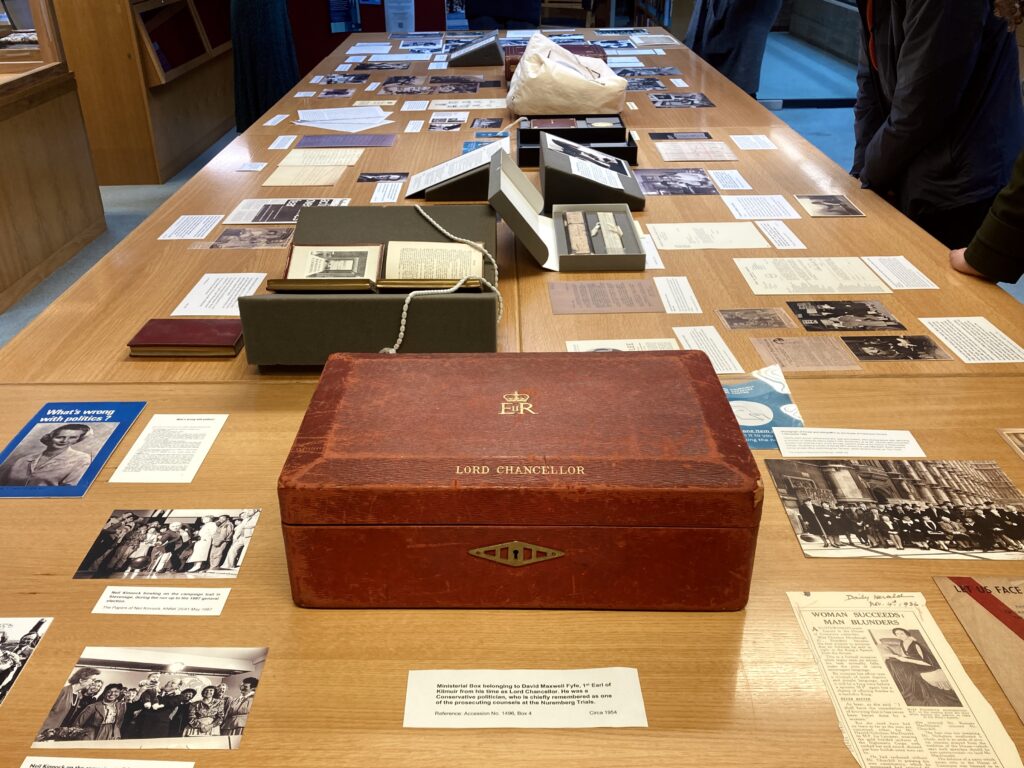

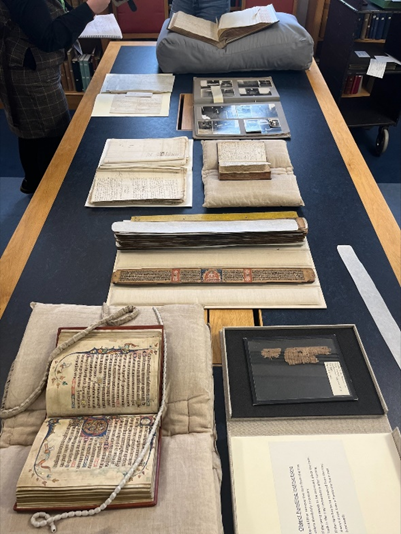

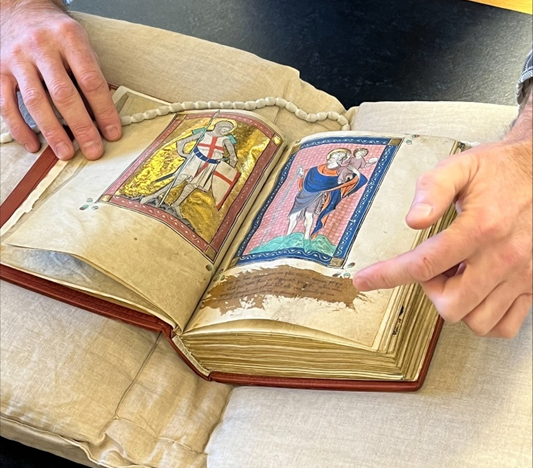

In front of the magazines, the librarian had laid out a selection of materials, showcasing the innovative ways poetry is experimented with. This included, for example, Anne Carson’s Nox, which is a box containing a long piece of paper folded like an accordion, featuring poems, photos, quotes, letter fragments, drawings, and more.

After browsing this selection, we were set loose to explore the rest of the library, taking our time to browse the reference and poetry books held in the rest of the collection. This allowed us to also peek down the rainbow sliding shelves – a feature which really adds to the vibrancy of the library space.

Thank you to the team at the National Poetry Library for introducing us to the vast collection as well as to the numerous ways the library engages with the community and gets people excited about poetry. This visit was a great addition to our day exploring libraries which either promote engagement with different media and art forms, or facilitate the development of artistic spaces.