On Friday 23rd February, the Cambridge Library Trainees came together for an online workshop led by the fantastic team behind the Decolonising through Critical Librarianship project. They began by introducing themselves and the work they do, all of which and more is collated on their website. The website is a rich and imperative resource for Cambridge librarians – especially those of us who are newer to librarianship and would like to know more about decolonisation and its importance as an ongoing practice in collections management. The University Library also recently established a Decolonisation Working Group, a separate group which works closely with the Decolonising through Critical Librarianship group, with an aim “to formulate guidance and policy for decolonisation work within Cambridge libraries and commission specific pieces of work to help encourage and embed best practice” (from the group’s Terms of Reference).

We began with an illuminating talk from Eve Lacey, Librarian at Newnham College, about decolonisation within cataloguing and classification. She spoke about the difference between widely used classification schemes, like Dewey Decimal, versus local schemes. The latter are much more adaptable because they are not subject to the often limiting categories of a standard system; they can change and evolve organically with collections, which makes them far more amenable to reclassification projects, such as those undertaken with the aim of decolonisation. This is why many Cambridge libraries use local schemes. Newnham library, for example, uses Dewey categories as a guideline, but classify under a local scheme which has made it possible for productive changes to be made. Eve gave a great example of this: the ‘Asian and Middle Eastern Studies’ section at Newnham was recently changed to ‘Asian and Middle Eastern Languages and Literature’, so more interdisciplinary texts were not omitted from relevant sections like History and Anthropology.

She then usefully spoke about the distinction between bibliographic description and subject description. Bibliographic description refers to the features of an individual book within a library, such as the classmark on its spine label. In an in-house scheme, this might contain coded information and innate bias based on the location of the book, the kinds of books it is shelved with and the subject classification it is given. These features can be problematic where, even if the item itself does not contain harmful or offensive content, the association of, for example, homosexuality with criminology (as was once standard) based on the item’s classmark/location creates difficulties. It is this kind of problematic tangle that changes like Newnham’s reclassification of AMES seek to allay. Subject description refers to standardised systems of things like subject headings, for which Library of Congress uses controlled vocabulary. As a result, Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) limit the ways in which we can organise by subject, and they can often be slow to change and update offensive terms. A recent change saw the term ‘slaves’ become ‘enslaved persons’ to humanise the people to whom the term refers. In 2021, a group of students at Dartmouth College lobbied the Library of Congress to change the subject heading ‘illegal aliens’, which they felt reflected an unnecessary negative bias. The LCSH was eventually changed to ‘non-citizens’ and ‘undocumented immigrants’ after the students’ journey of activism, which was recorded in full in their fantastic documentary, Change the Subject (2021).

After Eve’s talk, Frankie Marsh, Assistant Librarian in various STEMM Libraries, spoke about information literacy and decolonisation. Information literacy refers to the ability to search, manage, and use information e.g. on databases or catalogues. The ways in which we teach library users information literacy is suffused with our own personal biases and those of the institutions we are involved with. Frankie asks, for example, what the implications are of using only mainstream subscription databases, and information published in global north or written in English (as is the case for many educational institutions in the UK). Building on Eve’s points about the importance of classification, Frankie shared an example of how a reclassification project became a vital learning opportunity for students at the Scott Polar Research Institute. The Scott Polar was using categories outlined by the Universal Decimal Classification (UDC), which, like Dewey, often used outdated terminology. By involving students in the decolonisation of one of the Polar collections as part of an information literacy workshop, the staff were able to be transparent about the issues surrounding outdated and offensive UDC terms like ‘eskimo’, and make changes which informed, and were informed by, the Part II, PhD and post-doctoral students involved. (You can read more about the workshop in Frankie’s excellent blog post!)

I will reproduce a quotation by Sandra Littletree and Cheryl Metoyer, which Frankie helpfully uses in her blog post about the workshop: ‘The way we name and classify the world around us is indicative of our values and beliefs. The words we choose to identify elements in our world can illuminate, educate, and elucidate, or they can perpetuate stereotypes and misinformation’ (2015). The ways in which we manage information and the terms in which we present it are all tied up with our own individual biases and priorities. As librarians, it is important for us to understand the role we play, consciously or not, in both limiting and expanding the range of information resources that our users access – and to reflect critically on this responsibility. We discussed how this applies to library inductions and ways in which inductions could be adapted to target gaps in information literacy, which librarians may not realise are there; one idea was to have students submit questions beforehand, to take the lead on what they think they need to know. Peer-led tours, such as tours by older students, who are experienced in using the library, was another idea we discussed. We also spoke about the possibilities of signposting foreign language resources for multilingual students, of which there are many at Cambridge, and not just those studying languages.

Our discussion made me reflect on the way in which I process and display periodicals in Trinity College Library. The majority of serials we receive are in English, but many are foreign language publications which tend to get shelved directly in the basement, whereas many English publications will be displayed in the main library, a more accessible and browsable location. Since the workshop, I have tried to diversify the kinds of journals I display each week and include more foreign language publications, like Lire Magazine and Hermes : Zeitschrift für klassische Philologie. As a graduate trainee, it can be easy to feel like a small cog in a big machine, or that the responsibility falls to somebody higher up to partake in decolonising collections. But by taking my own responsibilities seriously and thinking critically about what changes I can make, however small, I feel that, alongside my colleagues, I can make a positive difference.

The next section of the workshop was led by Clara Panozzo, who spoke about the collection of cartonera books held in Cambridge University Library. She gave some important background information; in 2001, Argentina faced an economic crisis, which led many people to resort to waste picking, particularly cardboard, which could be sold for recycling. These waste-pickers are known as cartoneros (from the Spanish word ‘cartón’, meaning ‘cardboard’). Under these difficult economic conditions, publishing houses struggled to stay open. Two writers and an artist from Buenos Aires came together in 2003 to create an independent, non-lucrative publishing house, Eloisa Cartonera. They would buy cardboard from the cartoneros at a fair price and create handmade, self-bound books, often featuring work from voices outside the mainstream. Since 2003, the phenomenon of cartonera publishing has spread, and there now exist around 250 cartonera publishers across Latin America, Africa and Europe.

In 2013, Cambridge University Library began collecting cartonera books to form a special collection. This means the collection, now at around 300 books, is more diverse and representative of not only Latin American literature, but the forms which that literature takes due to specific socioeconomic conditions. Work has also been done to represent the material carefully in cataloguing and classifying it; for example, the records have been given richer bibliographical notes, subject headings, not only in English, but in Spanish, and/or other languages which relate to the item and its provenance. Care has been taken to provide information about those who decorate and bind the books, as well as the authors and editors of the text. Geographic subject headings are also made to be as specific as possible. The University Library ran cartonera workshops in 2019, allowing people to come together to learn about these incredible objects and try their hand at making their own. (Read more about the workshops here! You can also learn how to make cartonera books by watching this video.)

Clara pointed out, however, that the desire to democratise literature, which underpinned this project, was at odds with how the cartonera books are used, handled, conserved and stored. To keep them in good condition, the books have been stored in acid-free archive boxes, with their bright painted covers all but concealed from view. The tension between making the books accessible and preserving them for future use has meant that the cartoneras have moved quite a distance from how they would have been used and circulated in their countries of origin. By being closed off from people in library storage, the collection in some sense undermines the original ethos of cartonera publishers like Eloisa Cartonera, to make literature as accessible as possible. Furthermore, it was noted that very few libraries – including national libraries – actually host cartonera books in the countries where they are produced and circulate. The National Library of Mexico now has 11 cartonera books, but even this is a small collection compared to that of Cambridge University Library. As a result, the University Library has taken the decision to stop adding to the cartonera collection so that cartonera books remain available to be read and loved by people in the countries where they are made. From someone who had not heard of cartonera books, I found Clara’s presentation fascinating and have enjoyed exploring the collection further by reading blog posts on the library’s language collections blog and the DtCL website.

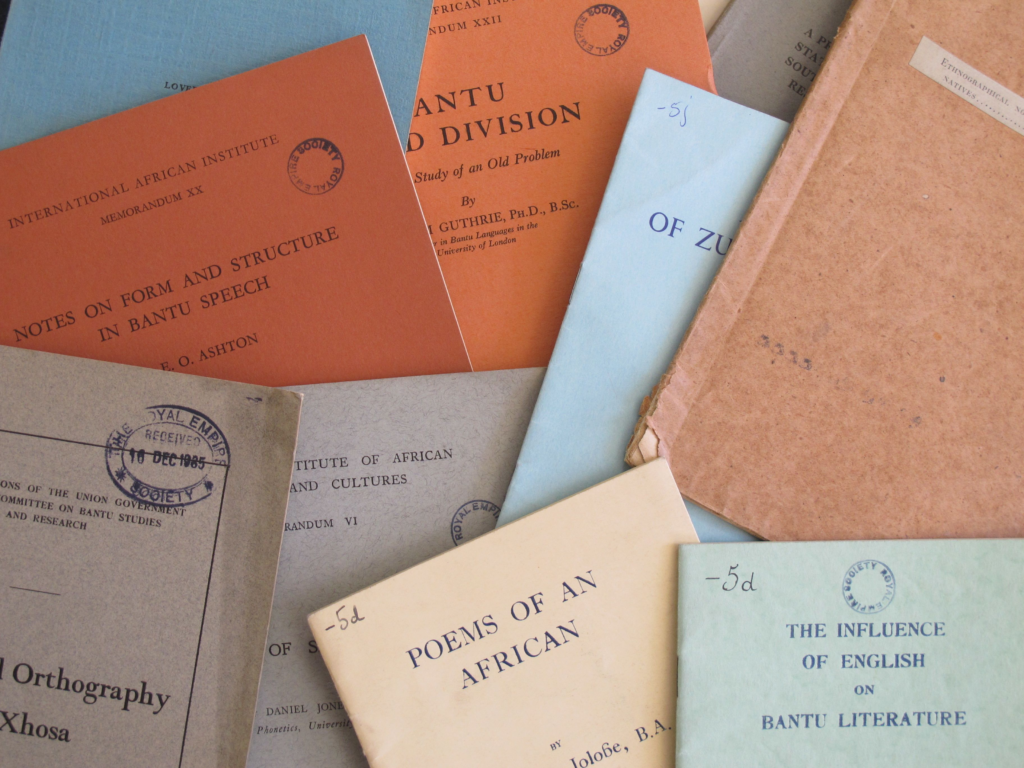

Finally, the workshop was concluded with a wonderful talk from Jenni Skinner, African Studies Library Manager, about a recent project to digitise the Royal Commonwealth Society (RCS) southern African collections held at Cambridge University Library. The project, funded by Carnegie Corporation of New York, began in 2021, and involved the conservation and digitisation of a vast range of materials, from cartoons, diaries and drawings to maps, pamphlets and photographs. These items hold great research potential but, as a colonial archive, they mostly represent a singular perspective. The project aims, as outlined on the website, are: to engage with groups or individuals in or closely related to southern Africa, to enhance our understanding of the RCS collections; to develop a digital collection hosted via Cambridge University Digital Library (CUDL); to carry out a concurrent programme of conservation, with targeted treatment of fragile items. By digitising items hitherto accessible only to those visiting Cambridge University Library in person, the project team were able to participate in the digital repatriation of items in the RCS collections to the southern African countries from which many of these items originate.

The project did not come without its difficulties, however. Jenni explained that there were some contentions around, for example, how items were selected for conservation and digitisation; by selecting items of a convenient size or format to be digitised first, the process immediately becomes selective and limiting. At the heart of the project was a notion of co-curation and co-creation, but such a collaboration between those involved in the project in Cambridge and in southern Africa proved difficult to co-ordinate. Research was performed by the Engagement Coordinator Chloe Rushovich, to identify gaps in African collections which the project hoped to help fill with digital repatriation. To balance the needs created by these gaps with the abilities of the team in Cambridge to conserve and digitise parts of the collection was itself a compelling challenge. Sally Kent has written a fantastic blog post with more details about digitisation of the RCS collections. Project updates can also be found here, and the digital collection can be viewed on CUDL.

Current Cambridge Visual Culture (CVC) fellows, Kerstin Hacker and Sana Ginwalla, worked closely with the RCS collections for a workshop which they delivered in October 2023. The aim was to engage members of Cambridge University and Anglia Ruskin University in a creative intervention, thinking of new ways to interact with archives. The workshop involved the screening of a short film, An Exhibition That Nobody Will See (available on YouTube) and a display of original material. This was followed by a creative session, transforming copies of archive items and into art pieces by cutting, pasting, collaging etc. to create something entirely new, thereby transforming the ways in which we think about and engage with the material. A full write up of the event, including pictures of some of the incredible work by attendees, can be found here! In 2024, the CVC fellows will be working in conjunction with the University’s Collections-Connections-Communities (CCC) initiative on a new project, ‘Re-entangling the visual archive’. Jenni spoke about what CCC is and the kinds of work it aims to do: it is an interdisciplinary research initiative, aimed at developing new ways of thinking about collections which address current concerns, including environment & sustainability, health & wellbeing, and society & identity. (More can be found on their website).

We concluded the session by reflecting on everything we had heard and learned, and discussing decolonisation practices we have seen in other libraries: St John’s College Library recently concluded a decolonisation project for their collection of Audio-Visual materials; Clare College Library has been reclassifying their history collection, with decolonisation at the forefront of the project; in 2021, Pembroke College Library undertook a reclassification project in their history section (read more here!); Queens’ College War Memorial Library have been doing ongoing work to identify areas where classification schemes are markedly Eurocentric or outdated, even adapting Bliss, a universal classification like Dewey, using local modifications to improve its terminology. This list is far from exhaustive, and library and archive teams are working hard to make changes big and small to continue the efforts of decolonisation throughout Cambridge libraries and archives. The Cambridge library trainees would like to thank the DtCL team for doing such vital work and for running workshops like this, which showcase the work being done across Cambridge and which educate us on how to continue this work in our own libraries.