A collaboration between Lauren Pratt, D Saxelby & Jess Hollerton.

Introduction

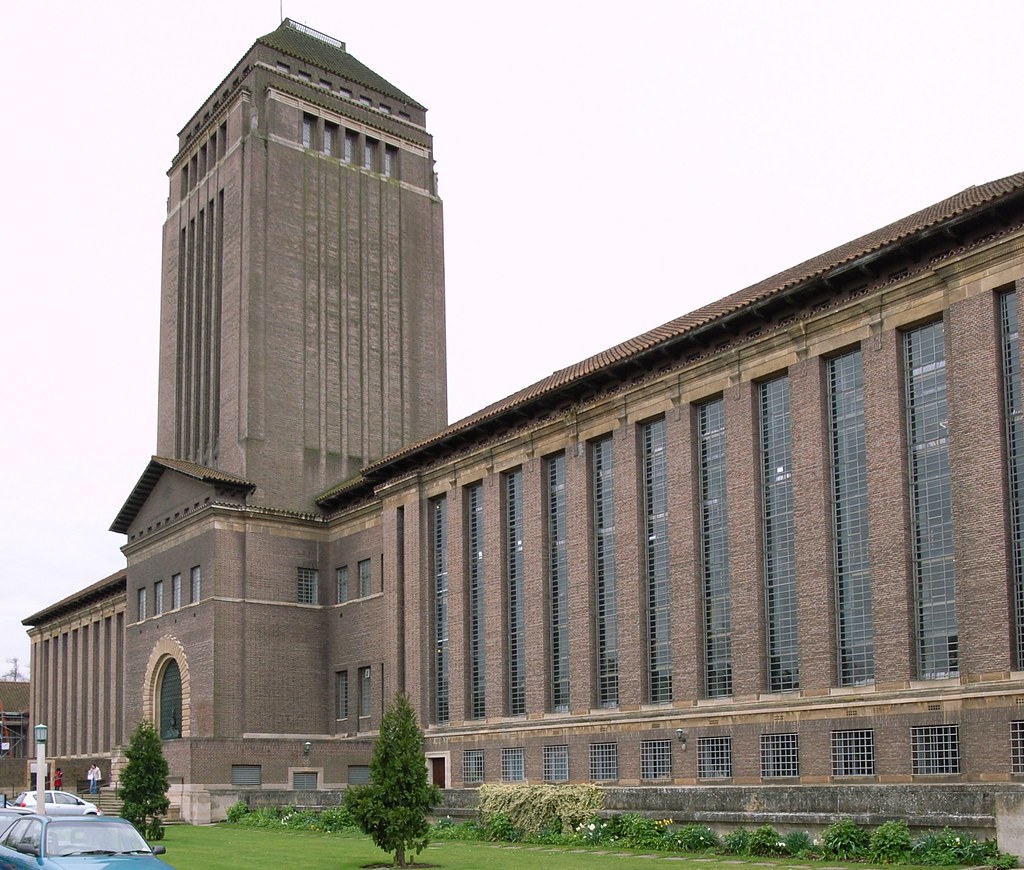

Something you might have noted from our other posts, like our post on a visit to Cambridge Central Library, is that we get many opportunities to tour different libraries around Cambridge. Today, we were lucky enough to receive an exclusive behind-the-scenes tour from the Cambridge University Library (UL), featuring talks from senior members of staff from a wealth of different teams. These included rare books, digital collections, cataloguing, legal deposit and acquisitions teams. I spent a lot of time as an undergrad at the UL, but never did I quite understand (or even think about) the scope and depth of effort and upkeep fronted by the teams here.

The exact date on which the University Library was established is somewhat up in the air, it’s generally agreed to be around the fifteenth century. No computers meant no iDiscover, no iDiscover meant no online records of books, no online records of books meant, well, they had to use paper records. So, if you were looking for a certain book, you had to (potentially) spend hours scanning through stacks of files until you found the written record and location of the book you wanted. I don’t think anyone could envision doing that in the 21st Century. Can you imagine trying to get by on paper records that are in one location? Hundreds of students fumbling over that one crucial text on the recommended reading list – sometimes technology is a good thing! It was interesting though, to grasp an idea of how technology has shaped the lives of these books.

On our tour, we saw incredible things, from a piece of manuscript from the 8th century written in ancient Sanskrit, to the personal diary of Charles Darwin, to a step-by-step guide on how Sir Issaac Newton undertook an experiment on the colour spectrum by sticking objects into his own eyes – ouch. It was incredible to discover just exactly how these teams fit together in one huge library jigsaw. Their day-to-day work is so diverse, yet the teams are united in sharing one common goal: creating the library.

General tour – Jess

It’s a well-known fact that that University Library is a bit of a labyrinth. The students tell horror stories about people who went inside and never made it out again, cursed to wander the halls of a modern-day Daedalus for eternity, another soul claimed by the hungry depths of the UL. (Or something to that effect, I may have over-dramatised.) Since my undergraduate degree, I have loved the UL immensely and I thought that after three years of using it while a student, there weren’t many more secrets it could reveal. I was, quite clearly, wrong.

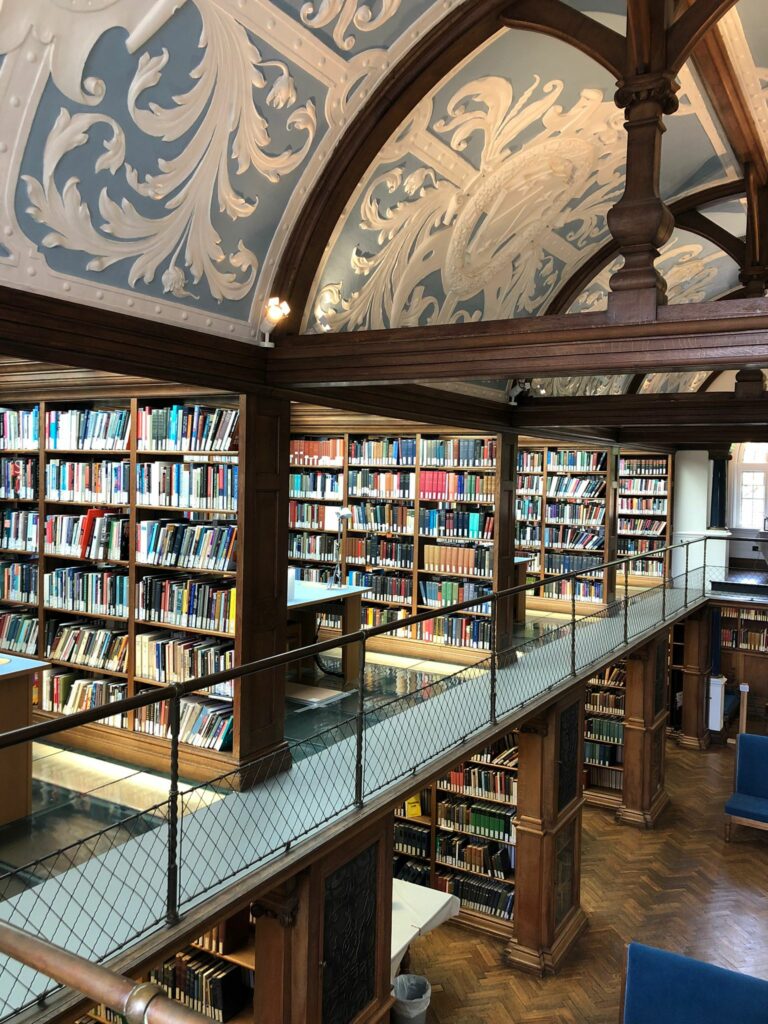

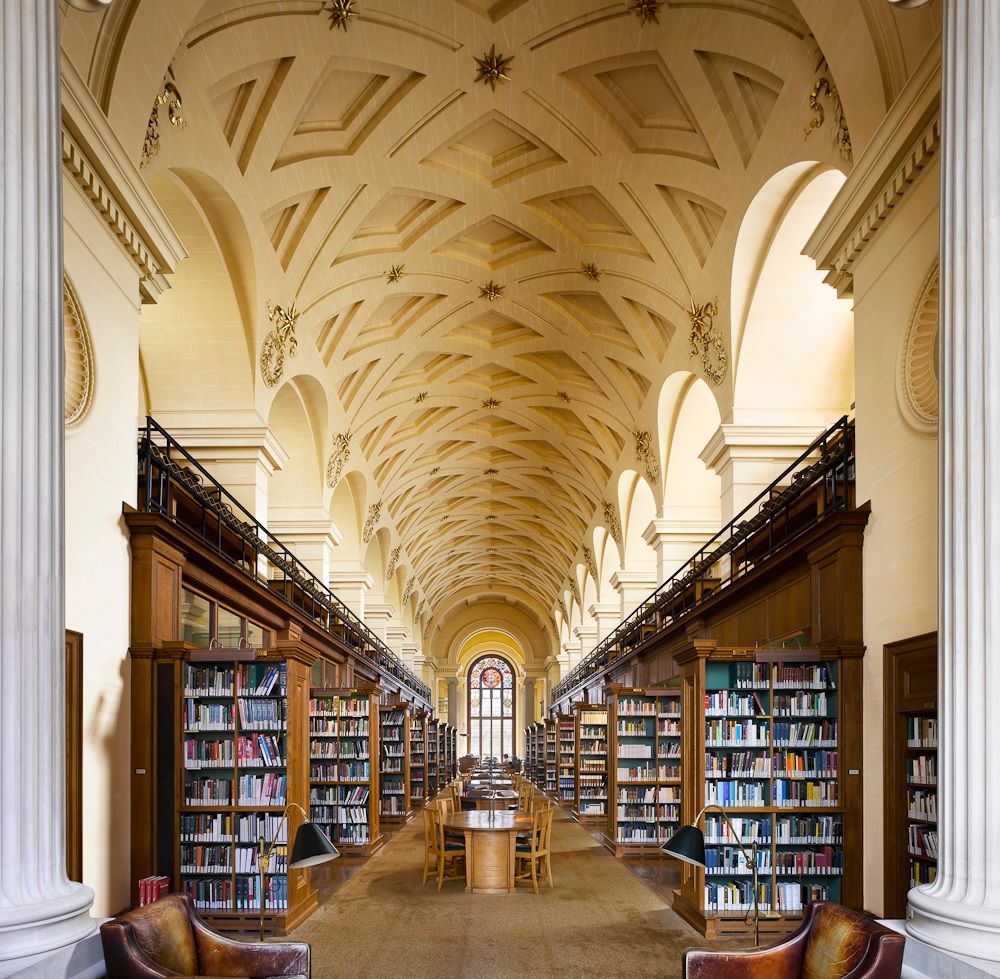

One of our first stops on our tour is the Catalogue Hall, a room which I had walked through hundreds of times before, but never paid any attention. The current catalogue for most libraries in Cambridge, including the UL, is hosted online but prior to this, as Lauren mentioned earlier, the catalogues were kept as books or written and filed on individual cards. The books which make up the former are still kept in the UL on open access, and together they take up all the shelving of an entire room. The card catalogue is also still accessible, the hundreds of thousands of records kept in tiny, perfectly sized drawers. Whilst it is not normally necessary to use these, there are apparently certain collections where the physical catalogues are still the fastest way to search them.

One of the things which distinguishes the UL from other legal deposit libraries is the amount of material which is kept on open shelving, available for any member of the UL to browse – and, for those with borrowing privileges, to borrow. The North and South Fronts and Wings, and West Four are all open access, as well as several other more specific collections. A significant proportion of the collection, however, is housed in either closed stacks or off-site storage. If you want to use these, they need to be requested and picked up from our next stop, the main Reading Room. As well as requesting non-borrowable material here, there are also desks for working at, and terminals for viewing Electronic Legal Deposit material. As we enter, the room is silent apart from the shuffling of paper and the clicking of laptop keys. It feels like how I would imagine a medieval scriptorium.

All this is accessible to all the UL’s members, but our next stop takes us behind doors marked ‘Private’, deeper into the library’s depths. As we entered the staff-only corridors, I lost my sense of direction alarmingly quickly, and was forced to follow close behind our guide for fear of never seeing the sunlight again. It was fantastic, and I could quite happily have done it all day. In one of the corridors we came across a huge set of grey-silver metal and glass doors that looked uncannily like the iconic red telephone box – which it turns out that Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, the architect of the UL, also designed. This warren of corridors led us into the sections of the library that are usually off-limits to all but staff, including the closed stacks, where on-site books that are not borrowable are stored, and the offices of various departments – for example, the Legal Deposit team and the Digital Content Unit, both of which we would visit later. One of the closed stacks we saw was the storage for modern journals and magazines. We were challenged to find the strangest or most niche magazine in the collection; I found a modern magazine for the Clangers and someone else found Scottish Beekeeping!

After this, our final stop was through another maze of corridors, to the Rare Books Reading Room, and I’ll let D, the Pembroke trainee, take over from here.

Rare books – D

While most of the college libraries in Cambridge have a special collection containing rare books, I wasn’t quite prepared for the treasure trove which was shown to us in the UL. Pembroke’s special collections are relatively extensive and very fascinating, but the UL has more rare books than I could have dreamed of – though we didn’t get to see just how many there were until the end of our tour of the rare books reading room.

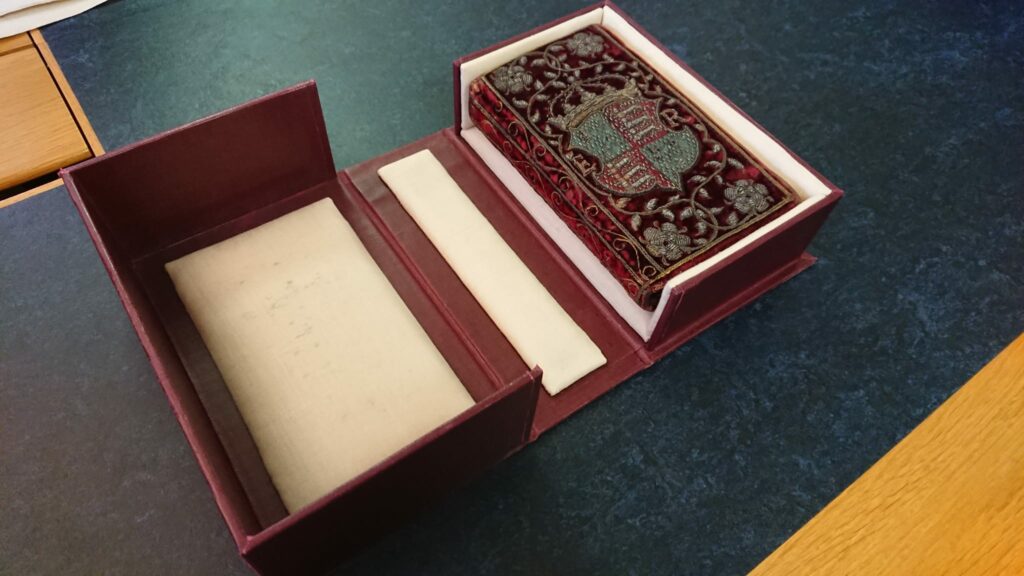

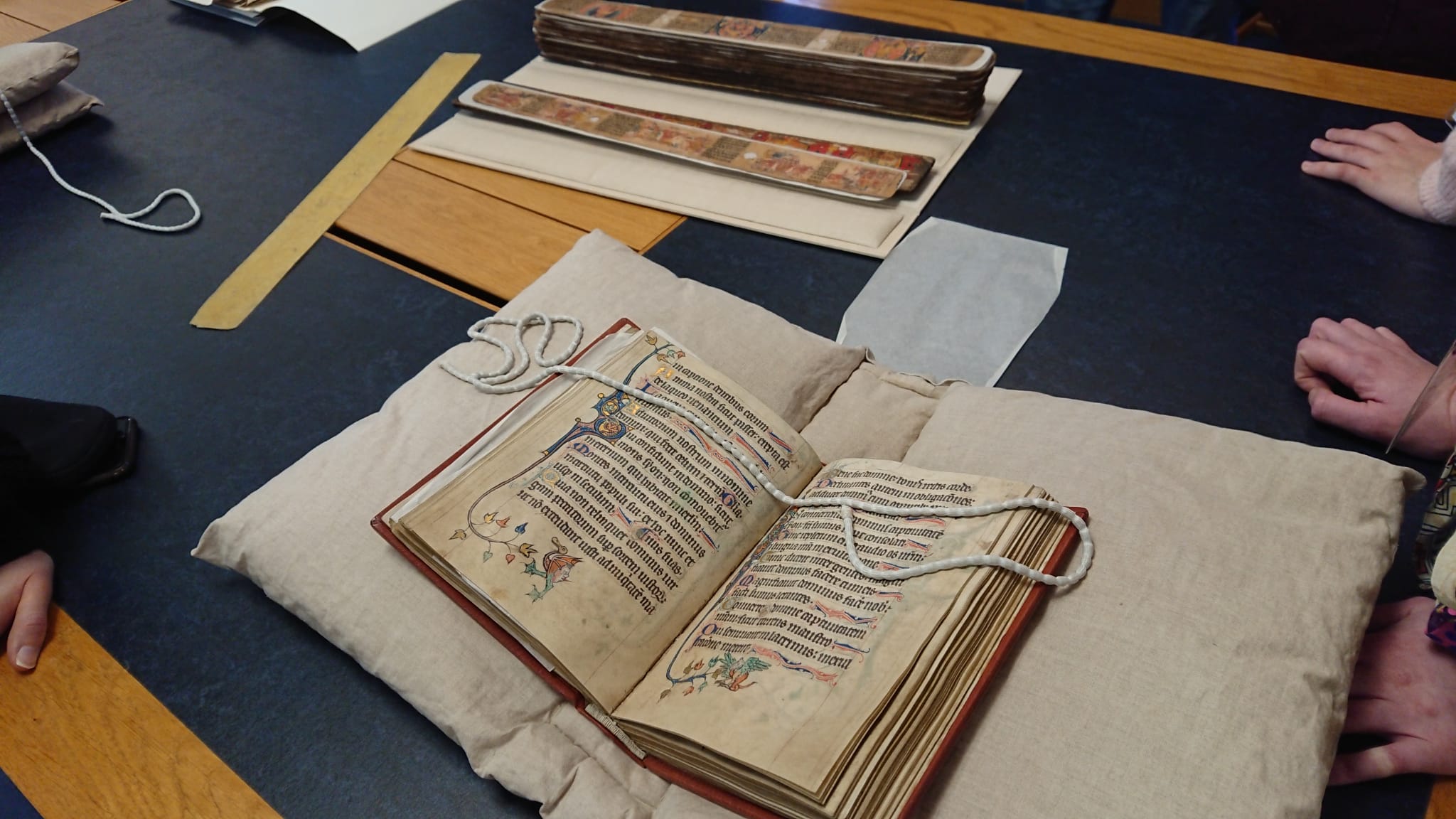

When we arrived, a member of the rare books team had laid out several interesting rare books for us to look at. Among these was a first edition of Shakespeare’s first folio (published in 1623), which was in pristine condition – it was almost impossible to tell that these pages were nearly 500 years old, other than for the discolouration on the fore-edge of the book. Unfortunately, this book was not in its original binding, but had been beautifully rebound in the Victorian period, an era in which ornate bindings were considered a sign of wealth. We can only despair that they did not see the importance of an original text – however it does mean that this book is steeped in the history of more than one period.

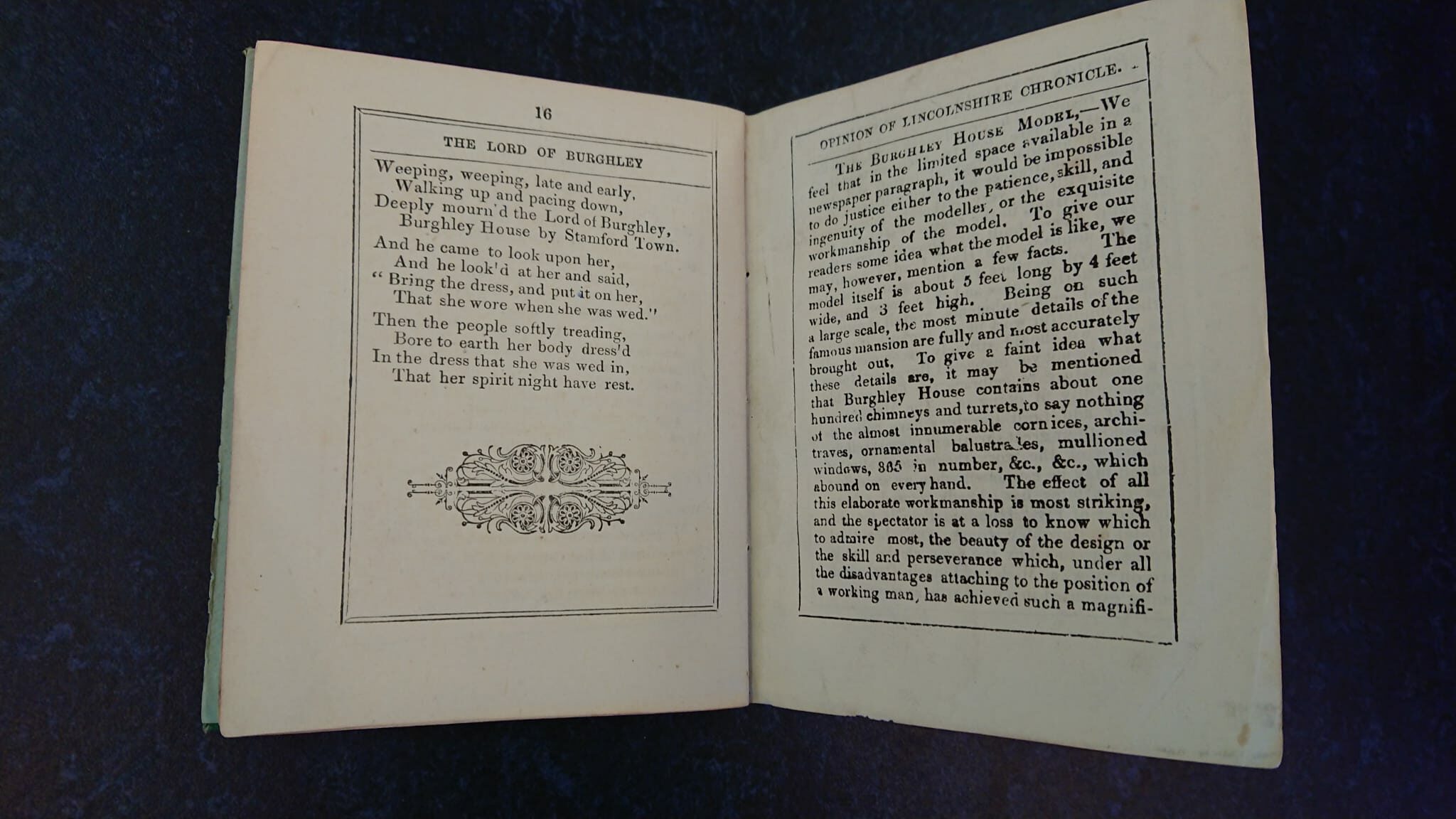

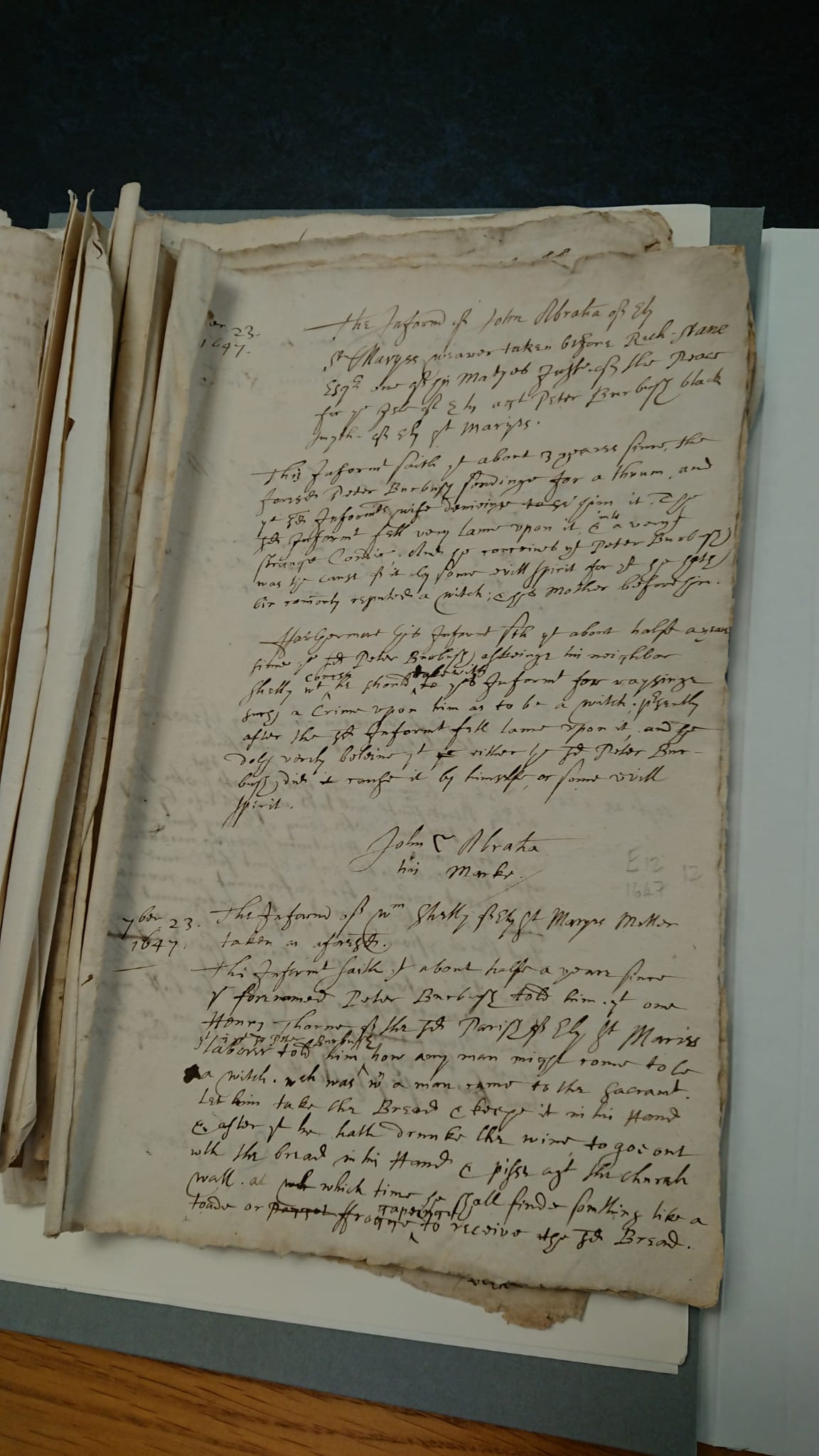

Similarly, we were shown a book which had been rebound with a red velvet binding, on the front of which was the coat of arms of Queen Elizabeth I. One theory is that this book was owned by Queen Elizabeth I, which would explain its luxurious binding. Another book which felt particularly historical was a medical textbook, in which a local apothecary had annotated descriptions of surgeries he performed. One of the annotations is suspected to be the first written account of what I think was a full body dissection, though my memory is not perfect, and unfortunately my palaeography skills are lacking when it comes to medical terminology! The passage begins: ‘1565. the 27th of marche I did make anatomie…’ and is written on reddish brown paper – stained by the blood of the corpse! It

seems that he had the book open whilst he performed the dissection, reading the relevant information, which has made for an interesting historical object!

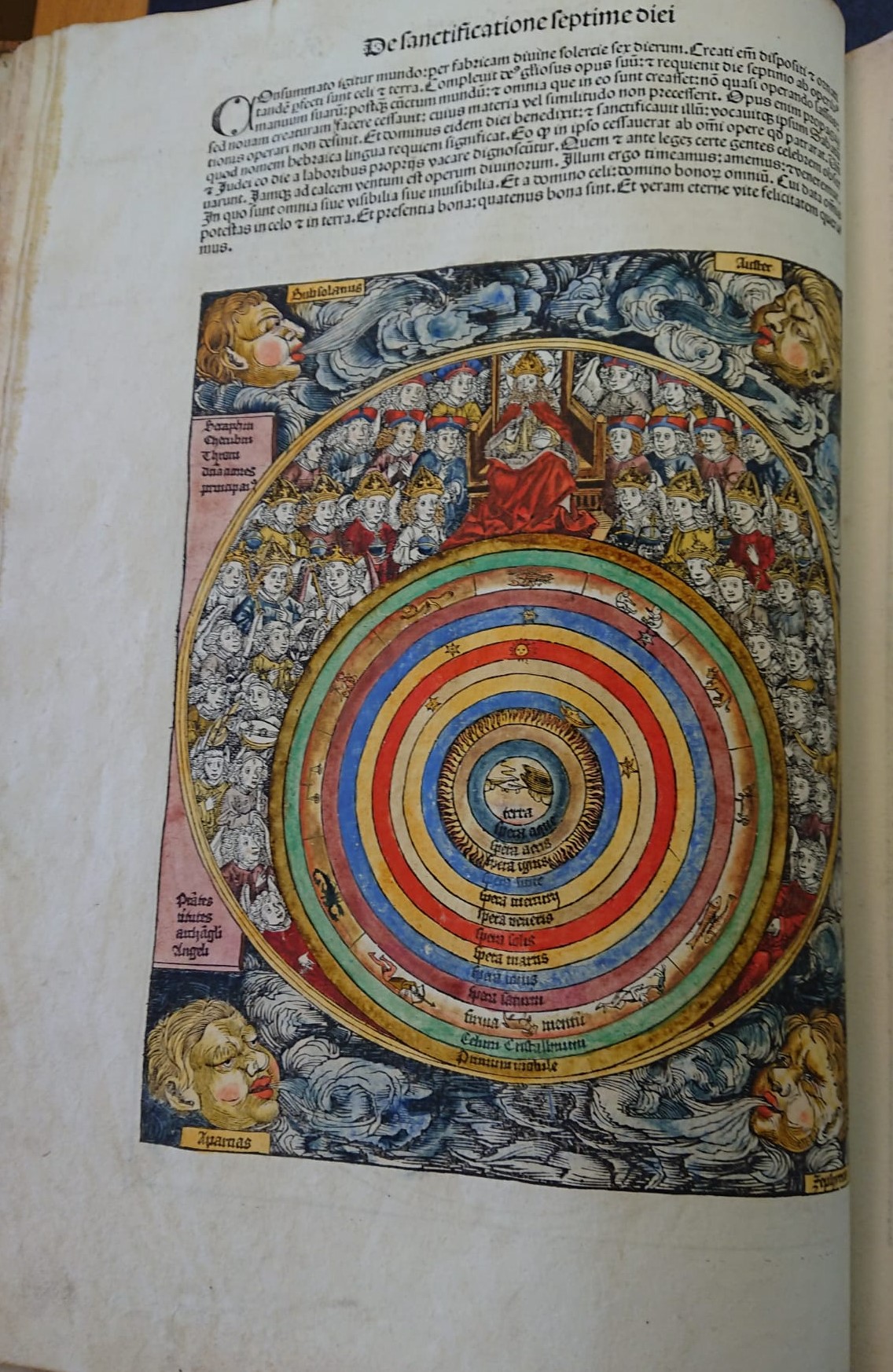

Particularly fascinating to me was a late 15th century text titled The Nuremberg Chronicle (the Liber Chronicarum in the original Latin), by Hartmann Schedel. Having done an MA in European Renaissance studies, I was thrilled to find scattered throughout this text many beautiful images, printed with illustrations suspected to have been made by none other than Albrecht Dürer himself! Although it cannot be confirmed which of the illustrations are Dürer’s, the suspicion seems highly probable in light of the fact that the publisher and printer was Anton Koberger, Dürer’s godfather. Like the first edition of Shakespeare’s first folio, this text was incredibly well preserved; the hand-painted illustrations still pop with colour 528 years after the book’s publication. To physically turn the pages of such historic texts made this part of the tour, alongside the manuscripts (which I will discuss later), the most exciting for me.

Finally, we were taken into an enormous room where the rare books are shelved – and then into another of the same size! It is impossible to describe how extensive this collection is without seeing it for yourself. These books are shelved using a variety of classification schemes, but one section that we all enjoyed learning about was ‘Arcana’, marked with the label ‘DO NOT FETCH’. The Arcana section contains a variety of books which were banned for different reasons (it is best to use your imagination here), spanning a large time period which leads up to texts that faced lawsuits in the modern world. These books are not available for viewing by anyone, and must remain on the closed shelves under lock and key – though they demonstrate just how exciting the position of Rare Books Librarian at the UL is – who wouldn’t want access to texts which can be viewed by no one else?

Digital content unit – Lauren

My highlight of the tour was the digital collections team as they fused creativity with technology to preserve the past.

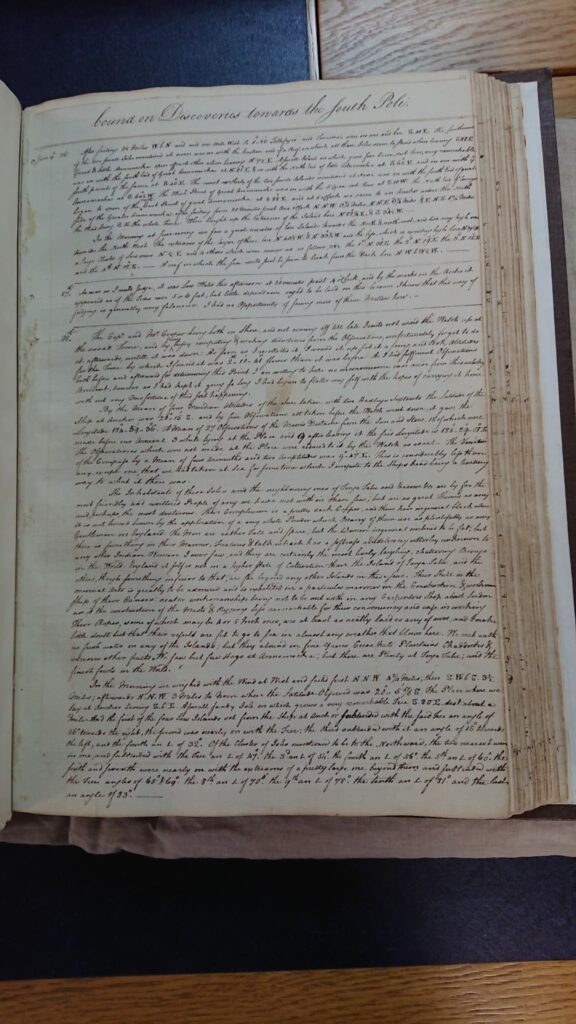

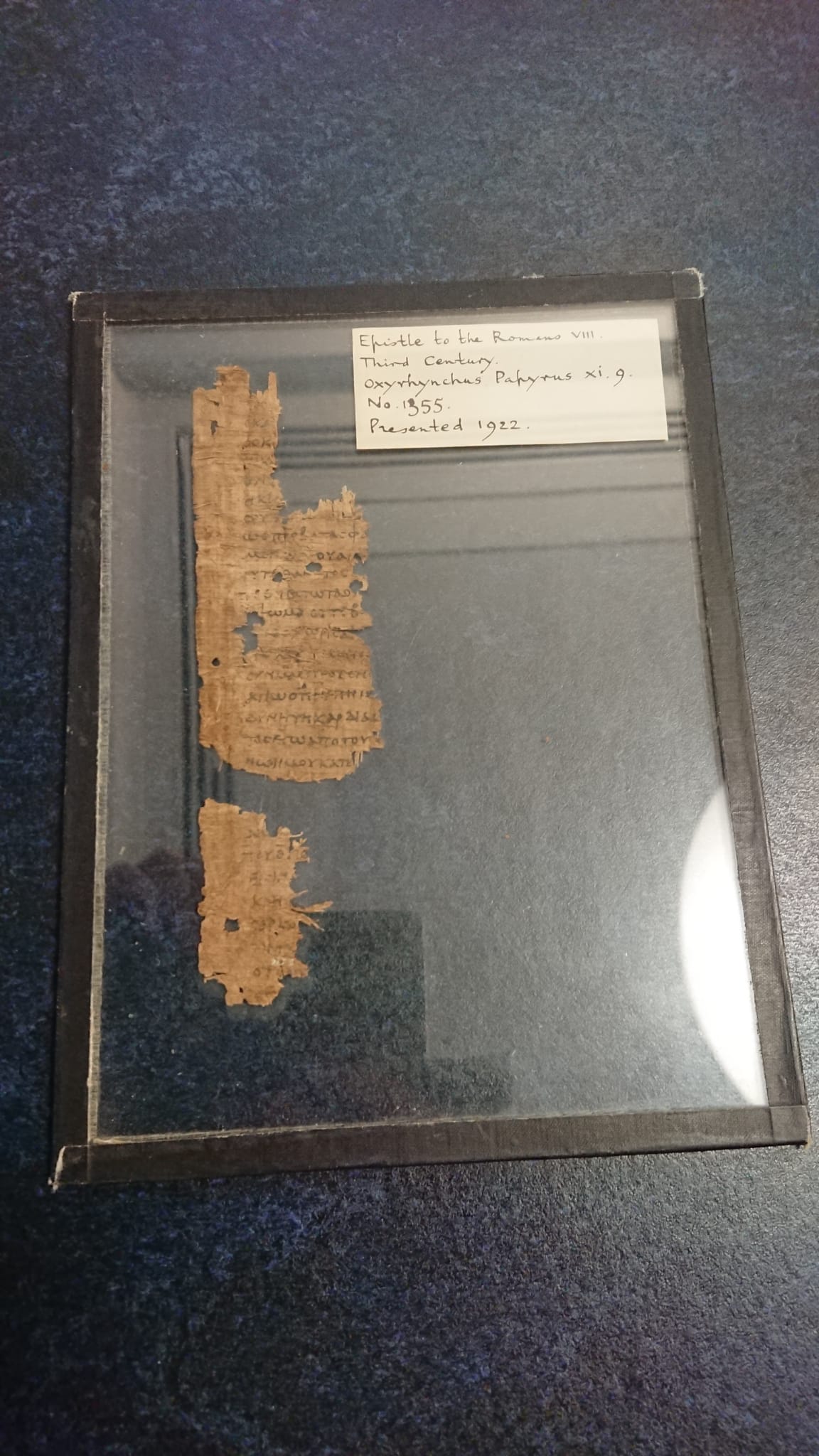

Fresh eyes laid upon texts that are centuries old can produce new, exciting perspectives for exploration and research. However, due to everyone’s favourite friend – aging – this is not always possible. Pages crafted from finite resources like crate paper or palm leaves after a while become too delicate for our oily fingers, the ink fades and becomes illegible. The wonderful words and beautiful artwork from thousands of years ago become forgotten, and the roads for research and new ideas close. Thankfully, the digital collections team at the UL have this in hand.

The kind of material that the digital content unit strive to protect

Armed with lights, cameras, and a plethora of new-fangled tech equipment, the team demonstrated just how they use modern technologies to their advantage, extrapolating methods from photography and lighting to preserve the delicate detail displayed in the library’s special collection. For instance, they can manipulate lighting to uncover text that had been written over. On that note, check out the UL’s exhibition ghost words which is based all around this! It runs until December 4th 2021.

It appears that, to become a digital archivist, a person can come from a diverse background. Not many of the team members had master’s degrees in library-related subjects, which is great news for accessibility. They also came from diverse academic backgrounds too. Supposedly, anywhere from computational linguistics to modern Greek, digital archives, media studies to physics.

Whether it’s historical significance or individuality of the item, or even scribbled notes of a mad scientist, it will tell a fascinating tale about the history of mankind, and thanks to this team, can now be looked upon by humans for generations to come.