We took a quick ramble through the streets of Norwich as we made our way to the Cathedral, passing the bustling and bright market, an adorable shop window decorated with jelly cats, and a lovely looking bookstore called ‘The Book Hive’ (that we sadly did not have enough time to gander in, which is probably a good thing for our wallets!). The first sign that we were near the Cathedral appeared in the form of St Ethelbert’s Gate, the medieval entrance to the Cathedral precinct. Passing under the gate, we glimpsed our first sight of the Norwich Cathedral Spire, rising into a surprisingly (for February) blue sky.

Café-ing and the Cloister cat

Entering the Cathedral, we took some time to enjoy the cloisters (which we later learnt is the largest monastic Cloister in England) and the amazing view of the spire it offered, on the way to the lunch spot that was recommended to us: The Refectory Bakery and Café, which is a modern café based on the site of the original monks’ dining room. While it was a lovely space, we were all quite disappointed with the food options, especially after running around the city had made us all very hungry. It seemed that Percy Pig sweets (from the train station M&S) was going to have to keep us fuelled. This was made up for though with the presence of the Cloister Cat (in the absence of knowing their name, this is what I have dubbed them because

who doesn’t love some alliteration), who basked in small slivers of sun coming through the windows, and had many, many pats from the trainees. The café was conveniently very close to the library, so in a matter of a couple steps, we were at our next visit spot: Norwich Cathedral Library.

Little lady in the in the cloister restaurant

How you blessed me:

…

You helped me as you shared a table

Partaking of a simple meal so warmly,

So lovely were you to my saddened eyes.

Snack in the cathedral restaurant (1985)

Reading rooms and modern theology collection

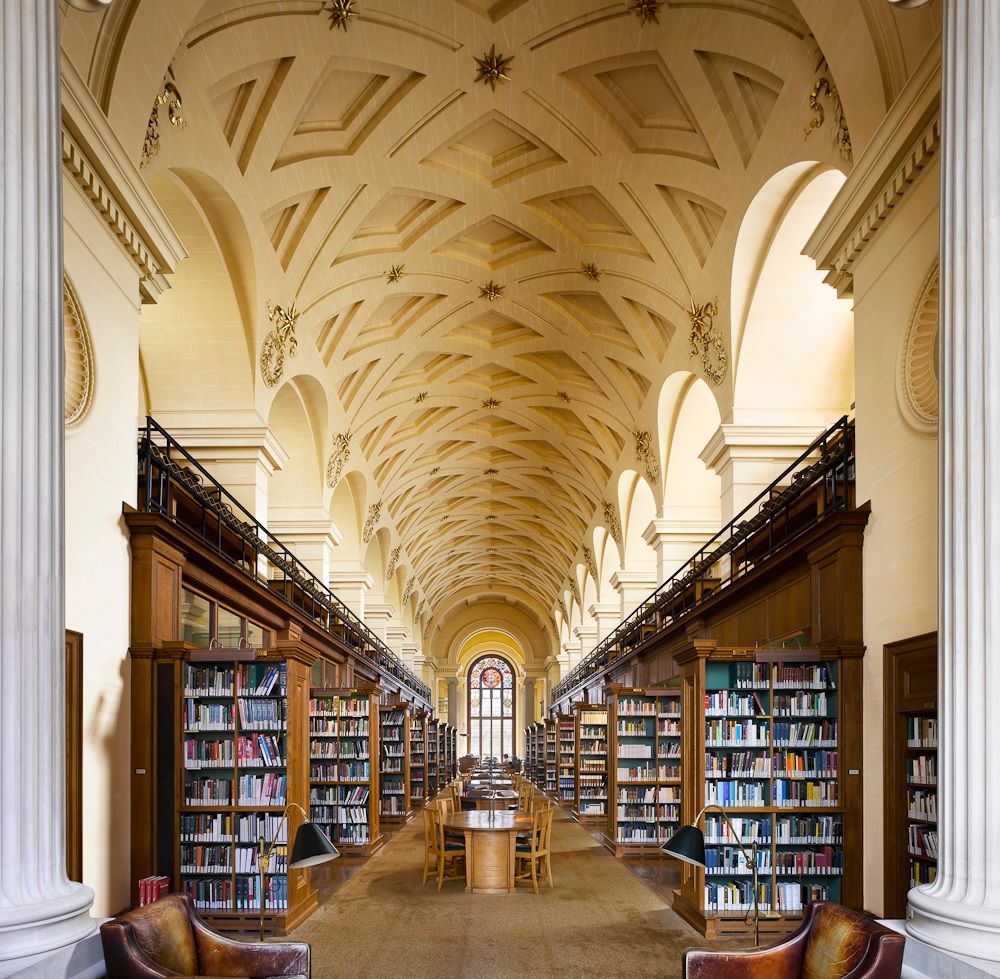

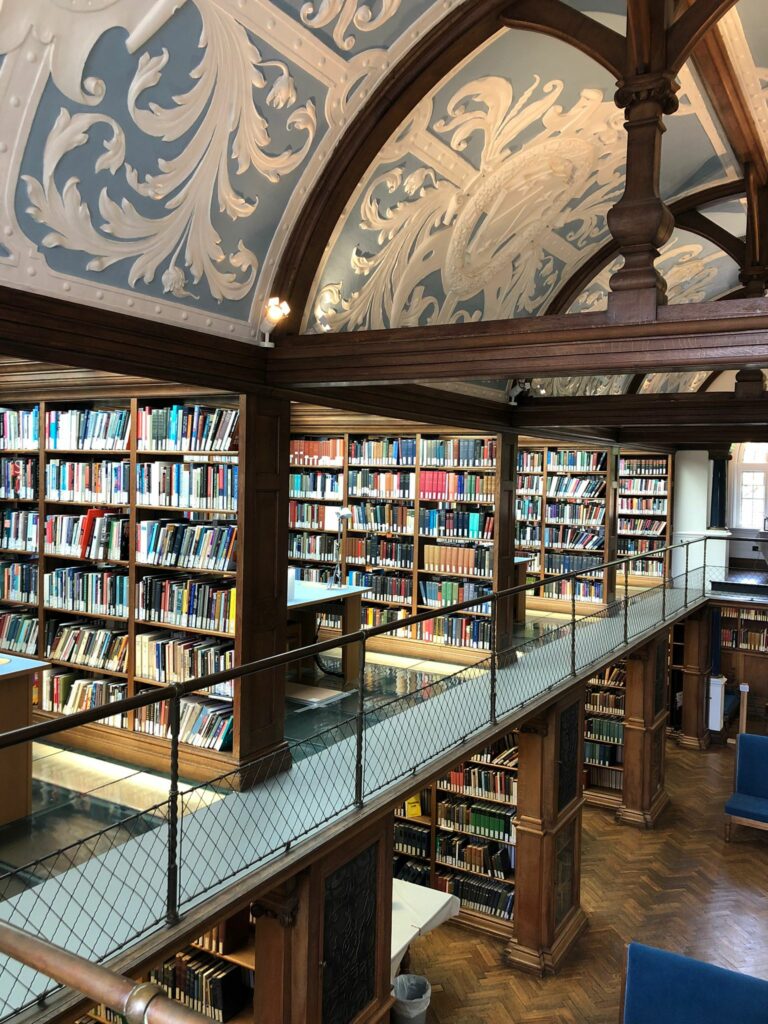

Much like the café space, the communal reading space of the library that you see on first entrance has a beautiful blend of medieval and modern architecture, that balance charmingly, allowing the medieval flintwork to remain, and remind visitors of the Cathedral’s history as a Benediction Priory, while being a visual marker of the development of the library with the Romanesque arcading from the 17th century. Both the café and library restoration were part of a major project to enclose the refectory space. The embroidered cushions on the reading room chairs were also a delightful touch, and it is here that we began our tour of the library.

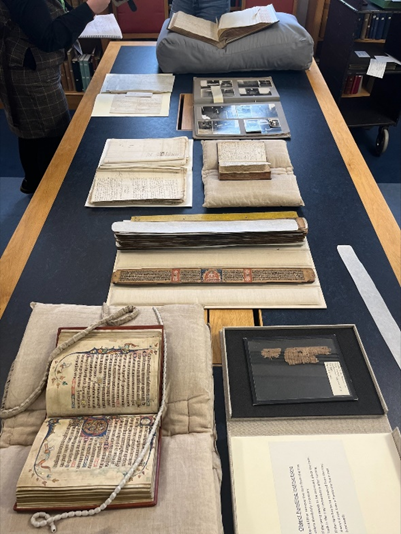

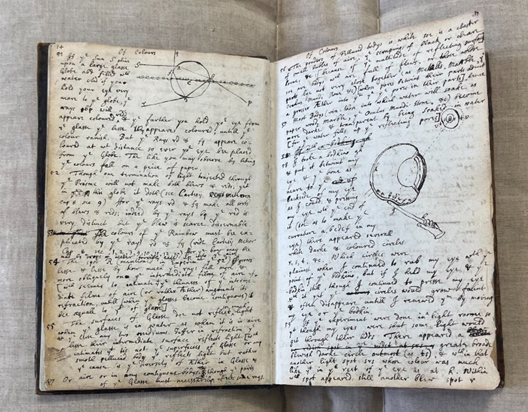

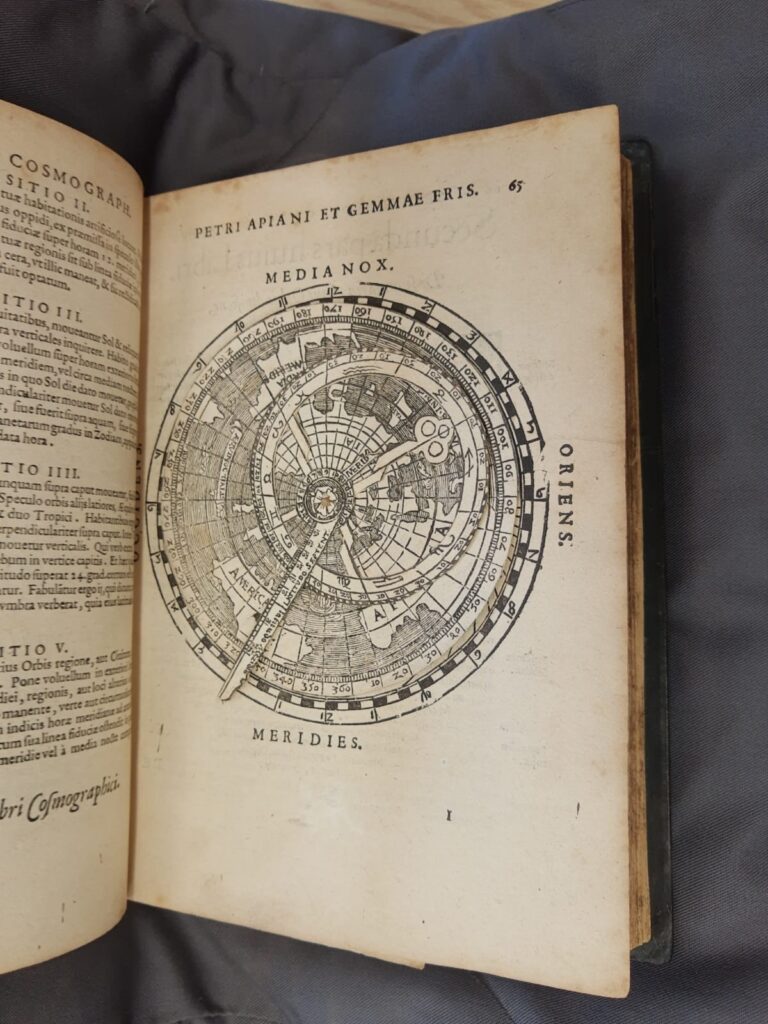

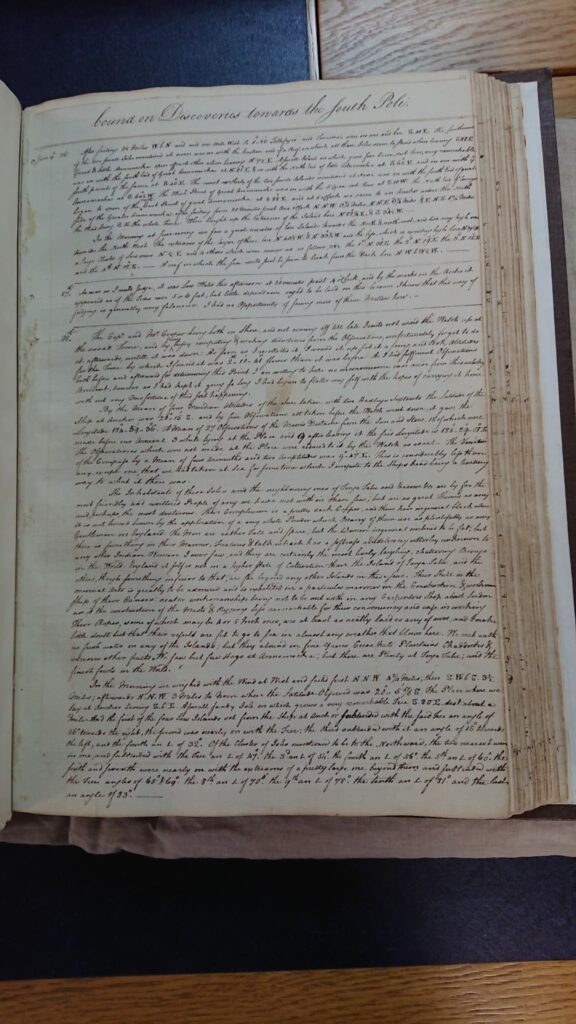

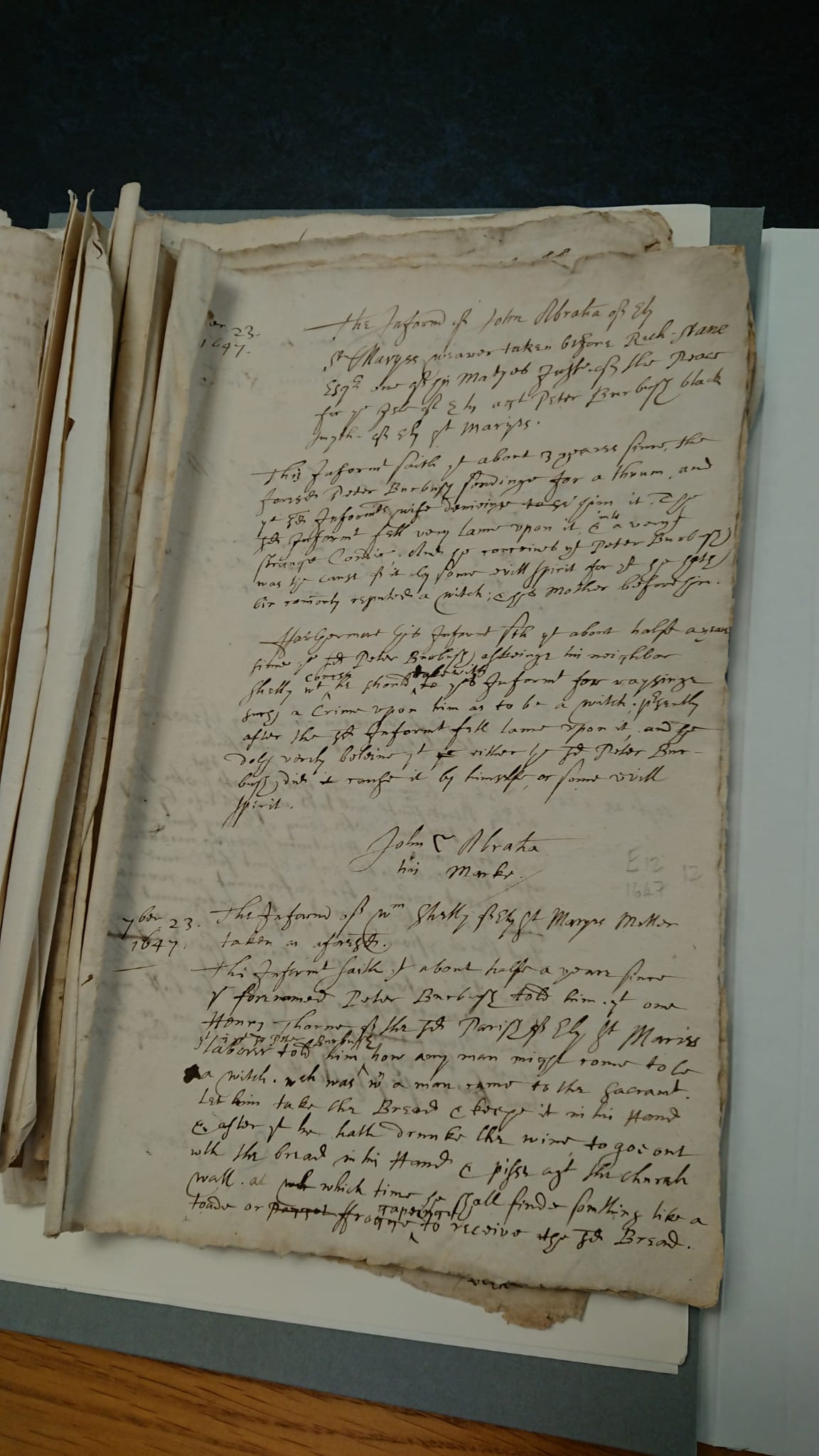

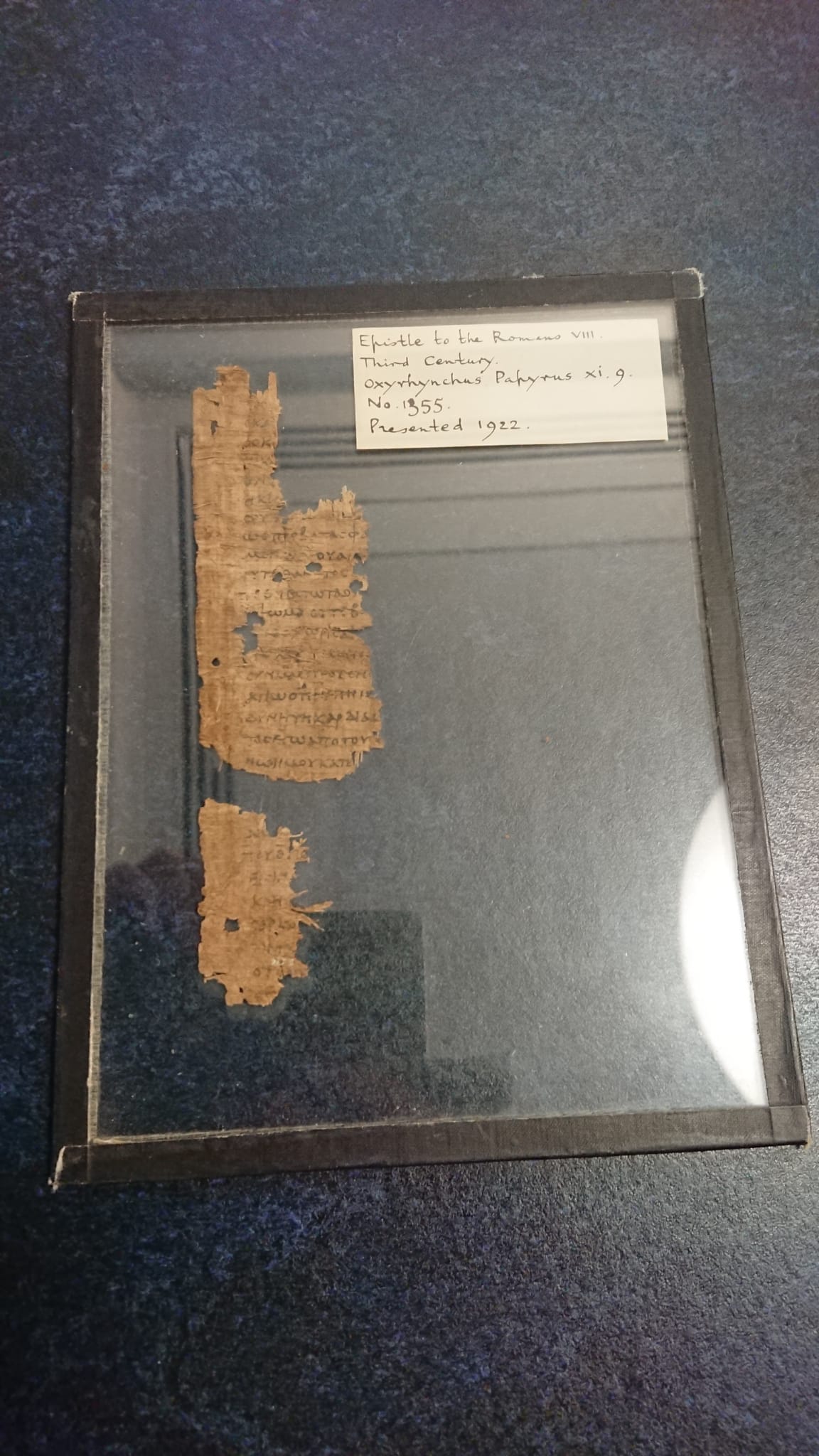

The Librarian began by explaining to us the history of the library, and how it relates to the history of the Cathedral; the original library of the Benediction Priory is believed to have held c. 1400 volumes of pre-reformation ecclesiastical and theological texts, of which only taxation valuation manuscripts remain at the library, with other manuscripts now found to be living elsewhere, including at several Cambridge colleges. This struck an interesting conversation regarding restoration, and where items ‘should’ be held.

As is often the case with Old Library collections, but particularly prevalent in a religious library, the Reformation had a large impact on the Cathedral library. It was explained to us that the Civil War also had a great impact on the Cathedral, as under the Church of England it was banned from operation. Recovery of the library began in approximately the 1680’s, and the Librarian explained that with some of the older rare books in the collection it is hard to determine whether they were here prior to this date or were acquired after this.

As we were located in the Reading Room at this point of the tour, the librarian also took the opportunity to explain the modern collection of the library; the books held here are part of the Anglican Training College ‘Modern Theology’ Collection containing c. 20,000 volumes. The library is free and open to the public but requires an annual subscription to borrow from the collection. The librarian explained that some people, such as students at the local university, just use the space for studying, while the texts are often references by the clergy who work within the Cathedral, but that there is also a level of tourism with frequent tours. They also hold events to foster engagement with the collection, such as ‘Listening Lunches’ which are an opportunity to collectively read books from the collection, with the aim of connecting back to the roots of the library’s purpose: monastic community development. The librarian further explained acquisition and material type policies for their modern collection; they have a small buying budget given by the Cathedral to fill gaps in the collection, and they do not have e-resources, nor do they collect journals. Like many libraries, they use the Dewey system for classification, but the Librarian explained how this can create challenges when the collection is specialised to one discipline, as most of the books occupy the same classification.

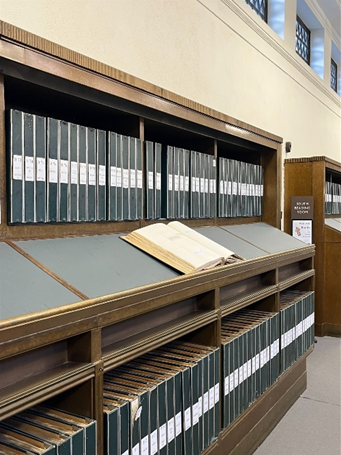

We were then treated to a wander along the winding bookshelves, which we were warned can feel slightly disorientating as they wrap and wind, but in reality you are just walking the length of the cloister. With many lovely dark-academia vibe corners to nestle yourself into by windows with gorgeous views of the grass maze and the cathedral tower, we could see why people would choose to study here! Though, it was rather cold, and the librarian explained this is a persistent problem with a building like this. Within the winding shelves the librarian pointed out some of the special collections which often felt like they were archival as well, pertaining to the history of the Cathedral and the surrounding communities: Crockfords for family genealogy; journals of Norfolk Archaeological Society; Norfolk Record’s Society transcriptions; Friends of Norwich Cathedral annual meetings and reports; past Orders of Service; and music for the Cathedral choir dating back to 18th century, including hand copied part booklets.

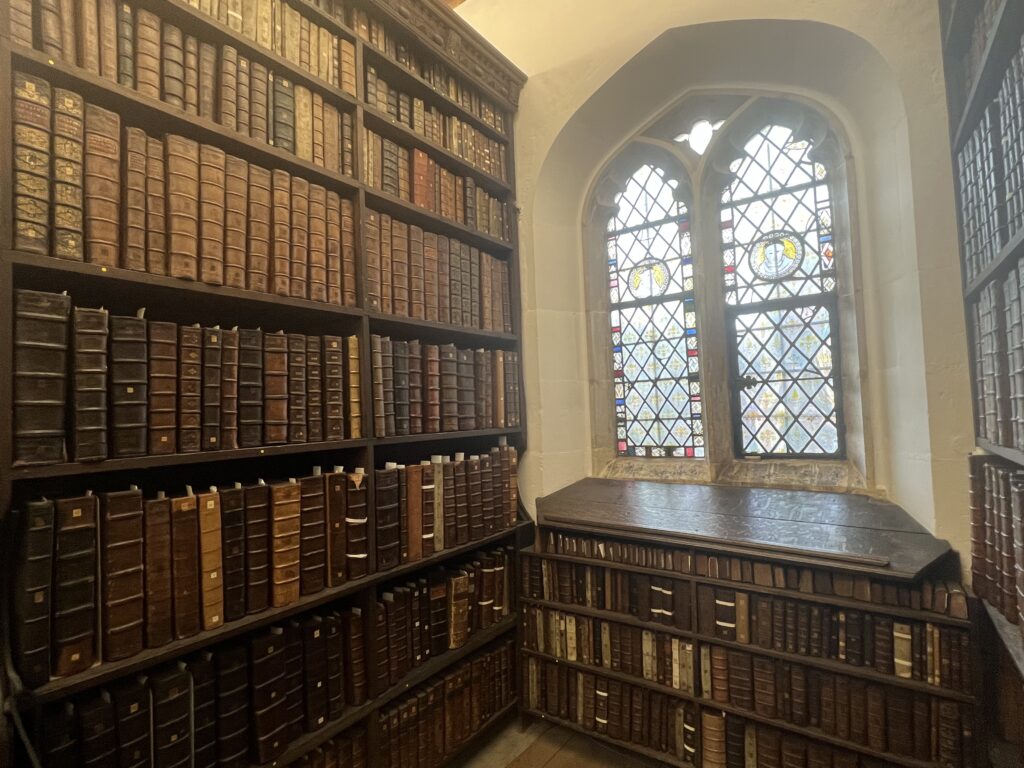

Historic collection

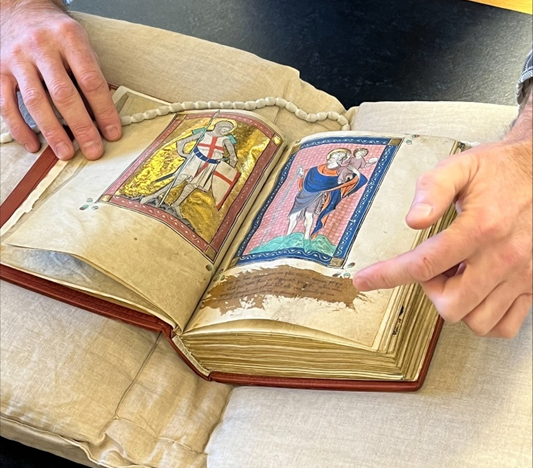

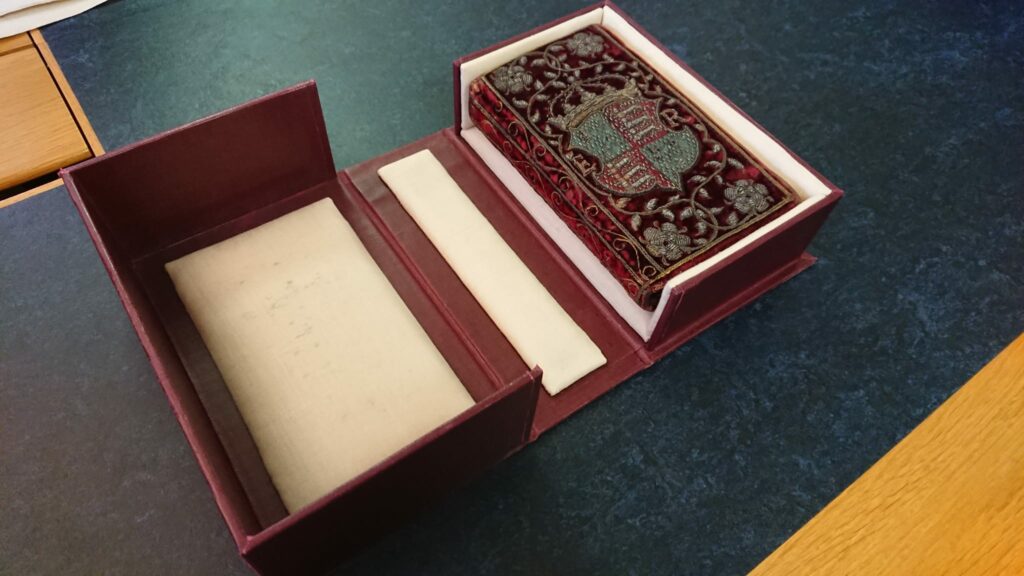

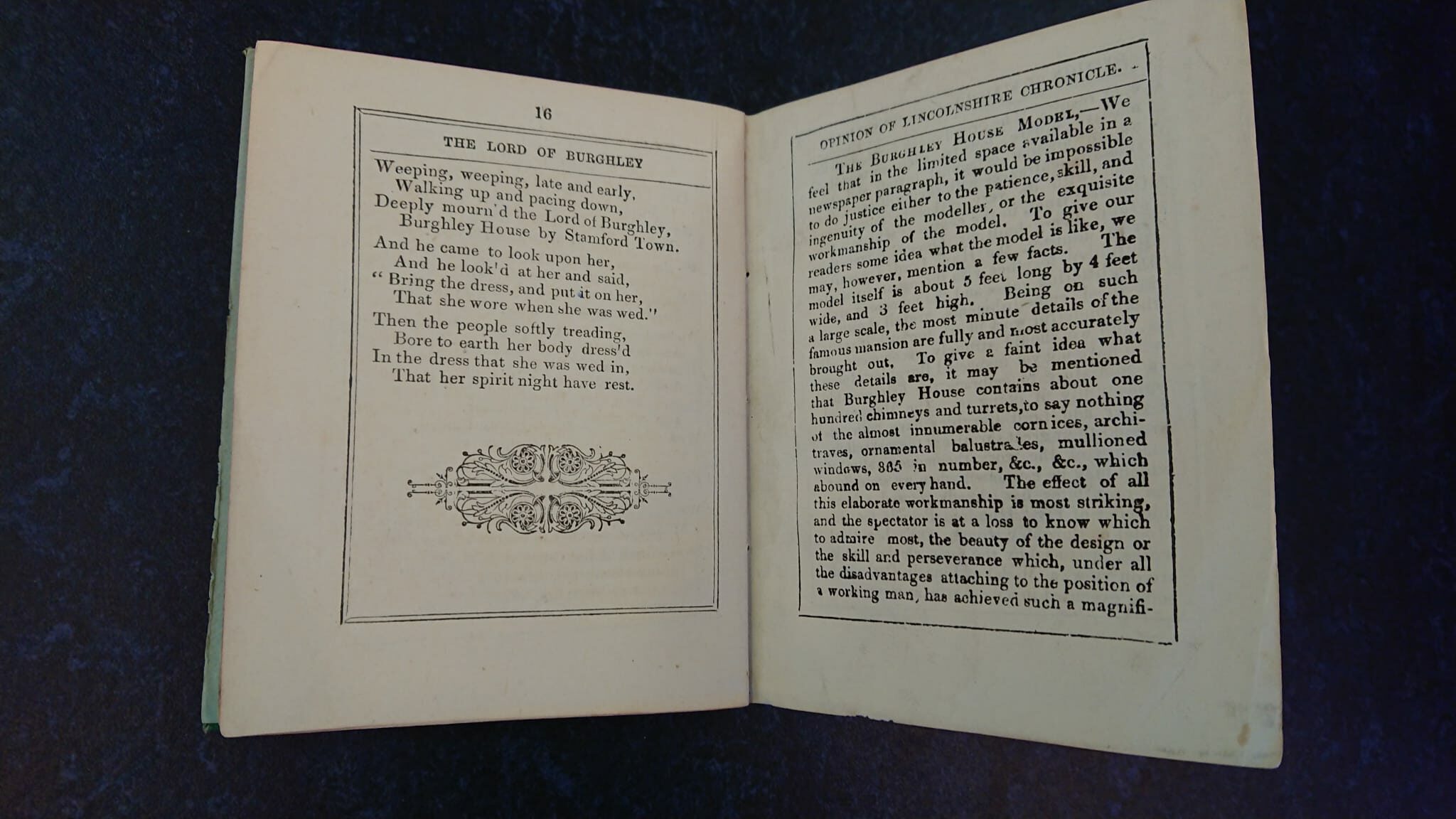

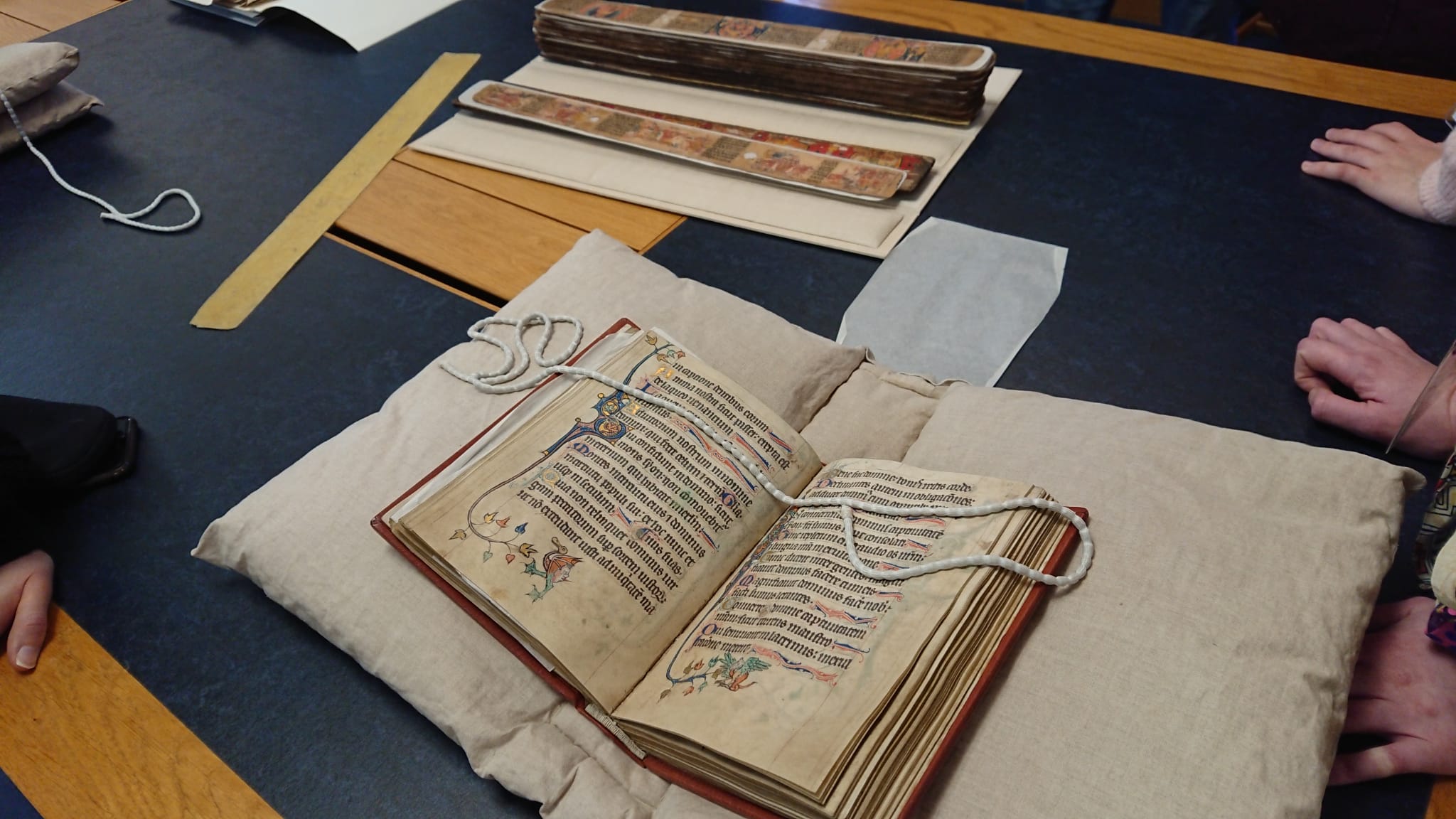

We then found ourselves above the South Cloister, where the Historic Collection is housed. Unlike the main collection, this space is only open to visitors upon special request, and for the purposes of consultation. We were briefly shown the current display cases, which had poetry ranging from early printed works and polemics on the Spleen and ‘The Groans of the Tankard’ to poems from the 2000’s regarding various parts of Cathedral life, including a poem entitled Books by Jenny Morris which expressed a sentiment we all could agree with:

Books are unlocked

Boxes of treasure.

The key is the library.

Books, bY Jenny Morris (2006)

All of the quotations I use throughout this blog post are taken from this display.

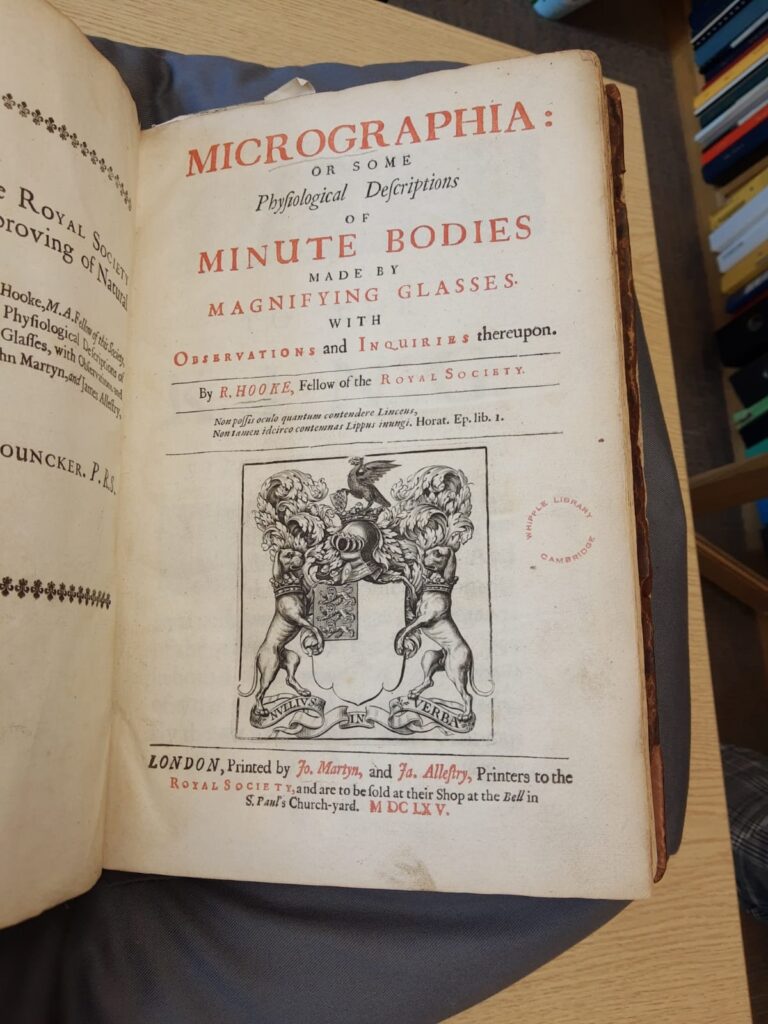

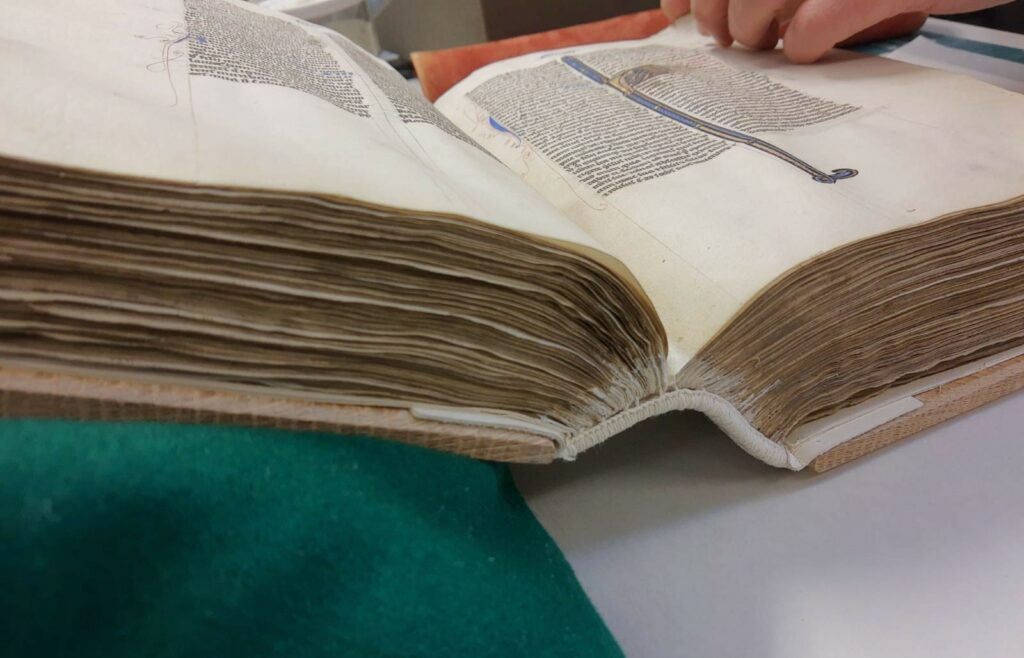

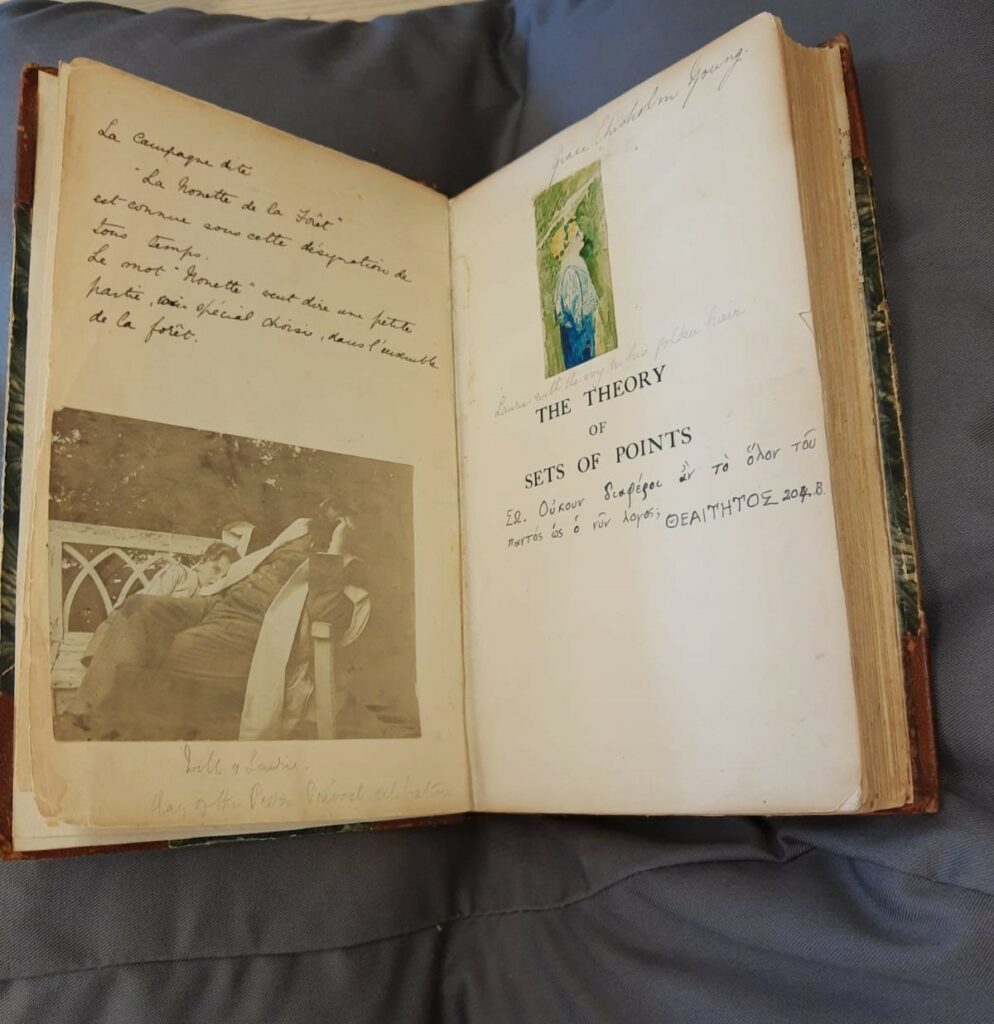

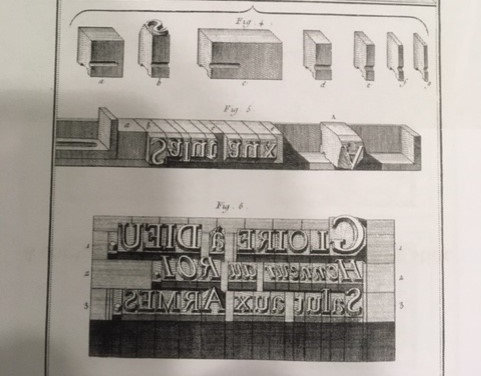

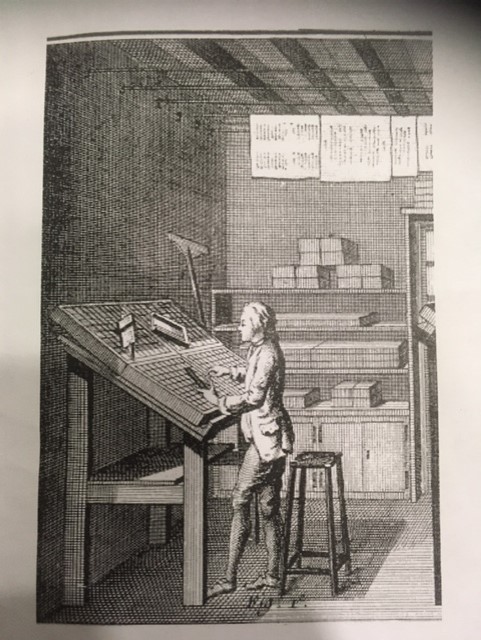

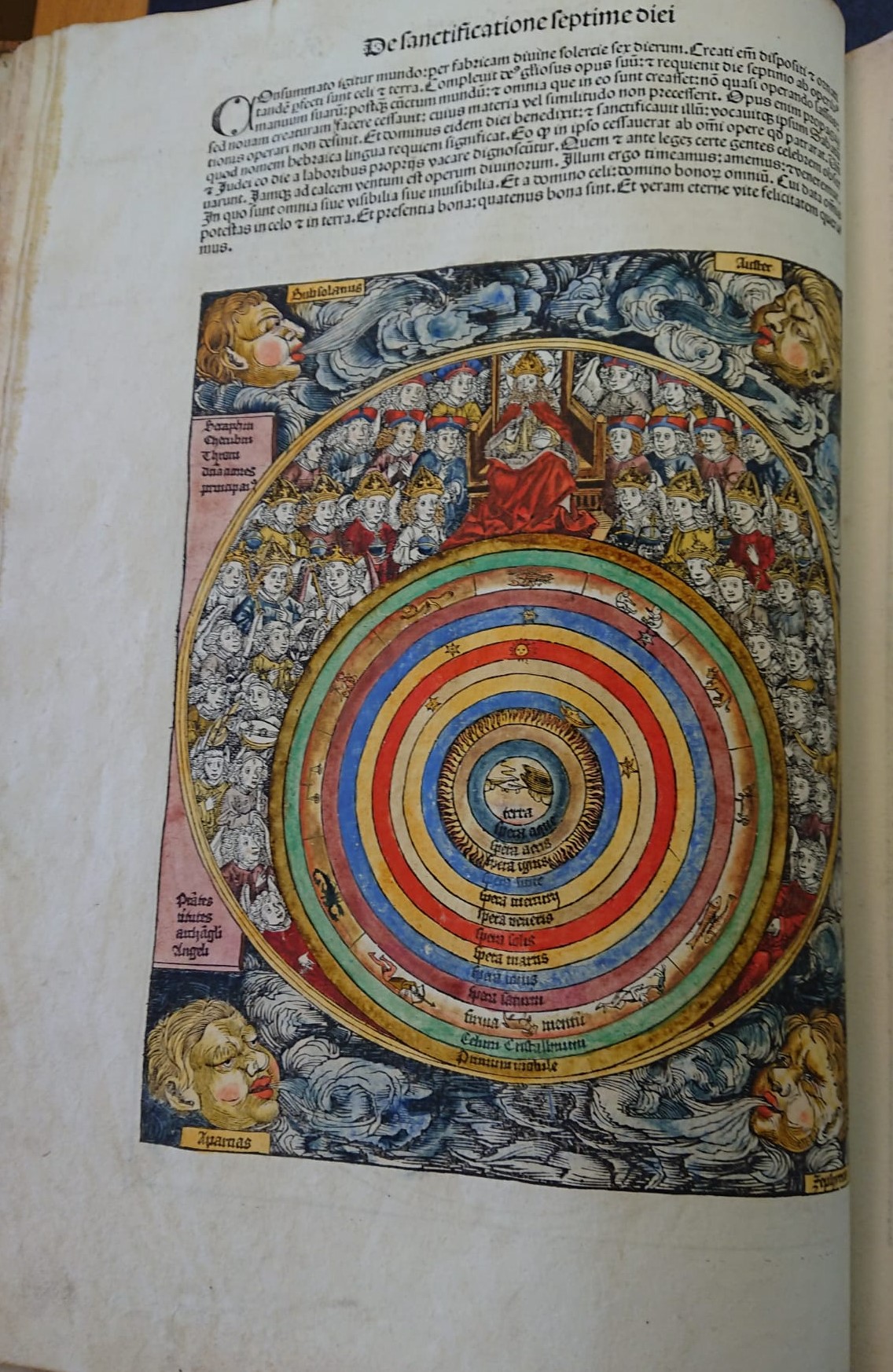

Walking down the length of the Historic Collection, which contains over 8000 books developed upon the private collection donated from Swaffham Parish, we were shown some highlights, including the equipment used for binding books, and boxes of typefaces. The librarian expressed the importance of these to a full understanding of early printed books, and explaining how she uses them in demonstrating to visitors to aid learning in a tactile way. In response to a question about restoration and conservation, we were also presented with a second edition of Foxes Book of Martyrs, which the librarian explained is in its present state thanks to a project to raise funds to conserve it, and for extensive work on the binding. By happenstance, the book was opened to a page with a detailed woodcut of the pyre of Anne Askew, which I found personally fascinating because I have previously researched the story of Anne Askew as part of my undergrad.

Though I am sure many of us could have spent many more hours exploring all the possible

nooks, interesting volumes, and various objects (paintings, vases) that the Norwich Cathedral library has to offer, as well as the opportunity to marvel at the beautiful cathedral, we sadly had to scurry off to get to our trains on time. Though, of course, we still managed to squeeze in a quick stop at the Cathedral gift shop for all-important postcard stock replenishment.

O why do you walk through the fields in gloves,

Missing so much and so much?

To a Lady seen from the train, by Frances Cornford

We would like to extend a huge thank you to the Norwich Cathedral Librarian, who was a fount of knowledge, and spoke to us with great enthusiasm.