In this blog post, the trainee at Trinity College (Lucy) and the trainee at Anglia Ruskin University (Ellen) reflect on the first library visit of 2021.

L:

On Tuesday 21st September, the new Library Graduate Trainees went on their first visit of the year – a tour of Newnham College Library. We were greeted by the Newnham trainee, who took us on an initial walk-through of the Library. I was struck right away by how welcoming the Library felt; you could tell that the space is fully focused on serving the needs of Newnham’s students. It was not a surprise to hear that the Library is one of the best-stocked undergraduate college libraries in Cambridge, and is kept as relevant and up-to-date as possible to enhance user experience.

Newnham Library has two sections: the original Victorian Yates Thompson Library (designed by Basil Champneys), and the Horner Markwick extension (opened in 2004). In the latter, our Newnham trainee guide pointed out the different subject sections, and explained the in-house classification system. Spread across three floors and with large windows to let in plenty of light, the modern extension of the Library felt like a wonderful place to study.

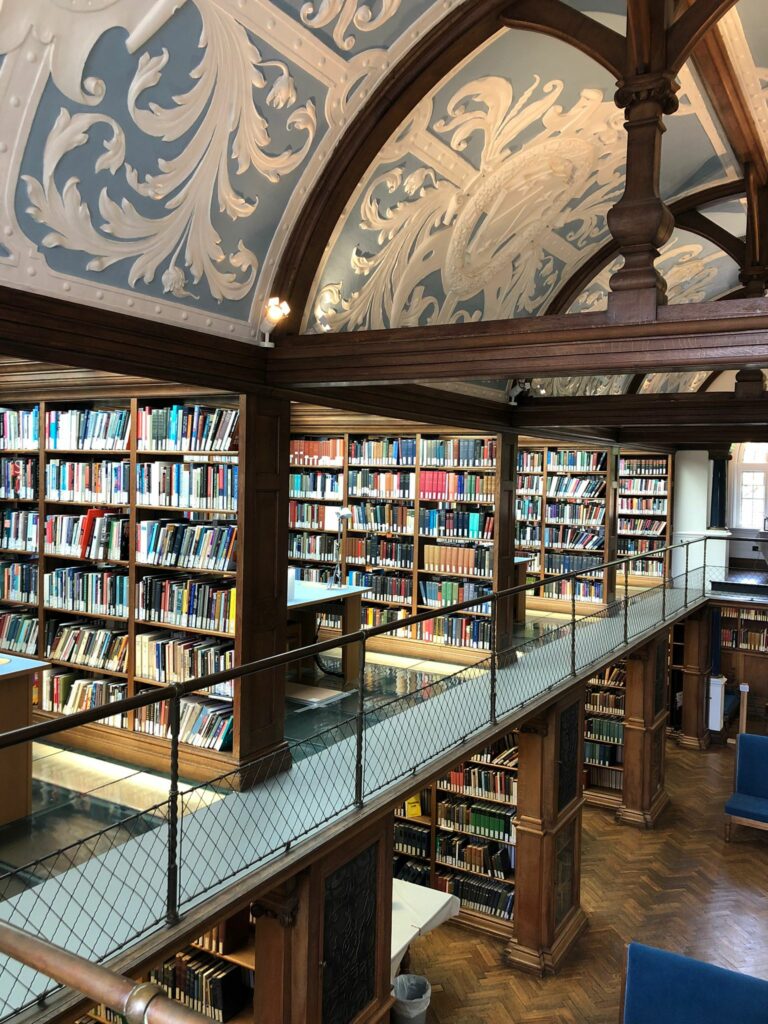

Next we moved to the Yates Thompson Library, a Grade II* listed building. All of the trainees were impressed by the blue barrel vault and ornamented ceiling, which is decorated with 13 early European printers’ marks (chosen by Henry Yates Thompson). A highlight was seeing a collection of first edition works by Virginia Woolf, which contained early examples of Hogarth Press printing. The dust jackets on a number of the books were particularly beautiful, including those for ‘Between the Acts’ and ‘A Writer’s Diary’ (both designed by Vanessa Bell, Woolf’s sister).

Over on the other side of the Library, we saw the small Glossographia exhibition, which displayed treasures from Newnham’s rare books and special collections. It was fascinating to see the first English translation of Don Quixote, as well as some unique reference aids, such as Thomas Blount’s ‘Dictionary of Hard Words’. A quick detour took us via the closed stacks in the basement, which house works from Newnham alumnae as well as materials that are not suitable for the open shelves. These included several boxes containing fake human bones, which are given to medical students at the beginning of each academic year – a somewhat unexpected and incongruous sight!

E:

One of the exciting features of our inaugural library visit was that it also included our inaugural archive visit! After the tour of the main library, we were split into two groups: one to look at the rare books collection with the Librarian, and the other to look at the archives with the College Archivist. For the Archives visit, we were led into a set of small offices, where the Archivist had selected and displayed some notable pieces for us. Laid out around the room were a number of books, posters, newspaper articles, and more.

The Archivist began by explaining that this year marked Newnham’s 150th anniversary as a women’s college, and the 100th anniversary of a rather unsavoury event in its history. In 1921, the University was voting on allowing women full membership of the University or ‘titles of degrees’ upon completion of their courses, where up until this point they would only have received a certificate acknowledging that they had taken and passed the exams. Some of Cambridge’s male students did not take kindly to this idea, and effectively stormed Newnham in protest. College property was vandalised, most notably the ornate bronze Clough Gates (commemorating Anne Jemima Clough, the first principal of Newnham) which were battered by a handcart.

As such, many of the pieces on display were about this event and the resilience of Newnham’s students that shone through because of it. One of the most memorable and amusing pieces was a letter of apology written by one of the men who took part in an earlier 1897 protest. In it, he professed his embarrassment at being there at all, and his shame at having accidentally broken a window in the process. He made an offer to pay for the damages and again apologised profusely, but at the end of the letter shattered this saintly image that he had painted of himself by asking, since he was Danish himself, if the college had any Scandinavian ladies studying there, and if so, that he be put in contact with them.

One of the more sobering pieces was a small poster from the 1897 protest, which in large letters simply said, “NO WOMEN”. It was a strikingly tangible reminder that attitudes like this were still prevalent only a hundred years ago, and that I sometimes take that for granted. I studied at Royal Holloway, which was very similar to Newnham – it was purpose-built as a women’s college in 1886 and educated suffragettes such as Emily Wilding Davison, but to my knowledge never had quite so much opposition. Seeing the dissonance between that experience and that of Newnham’s students was quite jarring!

We then moved on to the next room to view the stacks, where the archive materials are stored. The room was surprisingly small for a place with such a rich history, but I suppose that speaks to the meticulous curation and efficient organisation of the archivists more than anything. Truthfully, I could have spent the rest of the day in there quite happily, exploring all the different items on the shelves.

I was struck by the excitement in the room while looking at and talking about these materials. On a personal level, I had never given archive work a great deal of thought until this moment – I’d always thought it might be interesting to work in an archive, but I’d never really understood what that meant. Archivists are the caretakers of physical pieces of history. As well as exploring fascinating areas of the past, they get to decide what materials will be held from our time for the historians of the future. It sounds like an exciting and challenging responsibility, and I am certainly going to give it greater consideration going forward in my career.

L:

Our visit to the Rare Books room was led by Newnham’s current Librarian. Established in 1982 and built, stylistically speaking, in line with the rest of the Library’s architecture, the space was named in honour of Katharine Stephen. Stephen was appointed as the College’s first Librarian in 1888 and later became its Principal. She also happened to be the cousin of Virginia Woolf.

The College Librarian told us about Newham’s special collections, which contain approximately 6,000 rare books and manuscripts (ranging from the 15th to the 20th centuries) and result from donations to the College. This includes 16th century Chaucer editions, as well as both the Rogers and the Renouf collections. Many of the books are beautifully bound, with intricate patterns and gilding adorning their spines. The room was noticeably colder than the rest of the Library – the temperature signalling the priority that is given to the historic materials housed in the room over the librarians working within it!

We were also shown a small glass case, which housed a ring with the braided hair of Charlotte Brontë coiled inside. Just as we were leaving, the Librarian pointed out a recent donation given to the College – a first edition of an Aphra Behn play. On a personal note, this was wonderful to see, having briefly studied her work during the final year of my undergraduate degree.

E:

After we had viewed the rare books, and the other group had viewed the archives, we joined together once again and were led out to the college gardens. The Librarian was very patient as we collectively listed off the most complicated drinks order known to man, and before long we were all sitting together on the grass sipping our teas, coffees, hot chocolates, and chai lattes in the final rays of the summer sun.

Our conversation topics ranged from decolonisation workshops to films and musicals inspired by Greek mythology, and everything in between. I was interested to learn from the Assistant Librarian that there is in fact a library allotment somewhere in the 17 acres of Newnham’s beautiful gardens, and that they are growing blueberries there! I had never heard of such a thing, so it was a very pleasant surprise. Initiatives like that can make for a very enjoyable workplace and can do wonders for staff wellbeing. It made me wonder what other workplace initiatives might be possible for library and university staff more generally.

After we had finished our drinks, we got up and explored the college gardens and marvelled at the gorgeous Victorian architecture of many of Newnham’s buildings. Unfortunately, we didn’t get to see the library allotment, but we did see lots of lovely growing things, including tomatoes, pumpkins, and more than a few sunflowers. I hadn’t done any research on the gardens before our visit, so I was surprised to learn just how large and diverse they were, with innumerable varieties of trees, flowers, and other greenery.

One of our last stops was at the sunken rose garden. Down a set of stone steps were four large beds of roses, with a pool in the centre dedicated to Henry Sidgwick, Newnham’s co-founder. The flower beds were abuzz with activity, with a wonderfully large number of bees flying around. Honeybees were reintroduced to the Newnham gardens in 2016, for the first time since WWII. These are Buckfast bees, which are bred for their productivity, gentleness, and resistance to disease. The gentleness certainly came across, as they seemed to have no issue with us joining them to admire the roses.

Lastly, before heading off, we stopped at the bronze gate that had been damaged during the protest in 1921. It had, of course, been repaired since then but even so, seeing it in person added a huge weight of tangibility to that event. As well as a fascinating insight into rare books librarianship and archival work, this visit to Newnham gave me a renewed gratitude for the academic and professional opportunities I have as a woman in 2021, and I am doubly grateful for the generations of women who came before me to make that possible.

***

All of us graduate trainees are immensely grateful to the library team at Newnham for taking the time and effort to provide us with such a wonderful visit – thank you! It was the perfect way to start off our programme of library visits, and has set the standard very high.