In November, the Cambridge Libraries Accessibility Service gave a talk for the Cambridge Library Group on the availability of accessible services in the library, in particular on the availability of accessible formats.

The team detailed the process which is gone through to obtain accessible copies of ebooks. Although some ebooks are fully accessible, some publishers put limits on the ereader technology that can be used with ebooks. The accessibility service, however, are legally able to obtain accessible copies of ebooks by making use of the copyright exemptions for disabled people. The student needs to first be registered with the Disability Resource Centre to make this exemption legal, and the copy will only be made available to them.

A first port of call with often be the RNIB Bookshare service, which is partnered with publishers and often already has accessible copies of books to share with institutions. Institutions then make profiles for their students, so that a copy of a book is issued to a specific student. If not, the service can contact the publisher directly, either through the publisher’s accessibility team or (in smaller publishers) through the general contact. As a last resort a physical copy can be scanned, often through the Scan & Deliver team, and sometimes through faculty and college libraries. Further work may be done to make the file accessible (such as converting it from a PDF to Word to make it ereader accessible) and it is then transferred to the student or their support worker, usually through OneDrive.

The team detailed a breakdown of where they received their accessible formats from:

- Publisher (direct) – 29%

- Bookshare immediate download – 20% (the ideal method)

- Accessible eresource available – 19% (the work of the accessibility team here being telling the student that it is there)

- Scans – 12%

- Free/Open Access – 4%

- HathiTrust accessible text request – 3%.

There would sometimes be formats which required further remediation in order to make documents fully accessible for students. For example, sometimes chapters might be provided separately where it would be easier for the student to read them together, so the Accessibility Service would compile these into one document. Some of the greatest challenges are posed by scanned documents – a format which is labour intensive but might be necessary if the book is from before 2000 and no born digital file exists. (This is more prevalent in some subject areas with generally older books, such as theology).

In order for a PDF document to be made screen-reader accessible, it has to be put through optical character recognition software. However, even after character recognition, often a lot of remediation work needs to be done to fix mistakes made by skewed or distorted text, multiple languages (or non-recognised ones, such as Inuit languages), certain non-recognised fonts (and formatting such as italics and footnotes), damaged and defaced pages, images and tables, marginalia, and so on. While some software such as AbbyyReader can help with this, much has to be done manually, and there is often more than 2 hours of remediation work per title. The Library Accessibility Service also helps with other format requests, such as compiling multiple chapter files into one document.

There can also be some difficulties when dealing with publishers. Although publishers very rarely did not reply, they could often be slow to respond – 32% of requests took more than 10 days to fulfil, which can be an unworkable length of time in term time. Some law publishers will also not supply what they consider to be practitioner texts, although they will supply academic texts. Some publishers attempt to impose unacceptable terms and conditions (for example, some American publishers assume students will buy their own copies), while some publishers are simply hard to contact, with no accessibility information on their websites or the contact details of the accessibility department hard to find.

Many ebook platforms themselves can also be either impossible to use or extremely difficult, as the demonstration of JAWs technology revealed. The speakers noted many students would ideally have a folder with all the PDFs rather than lots of individual clicks – part of the Accessibility Service’s job was simply finding things to pass on to the student. The university also owns 39% of requested titles already as eresources, but 49% of these weren’t compatible with the student’s assistive technology. Accessibility could be massively improved simply by publishers making their platforms more accessible and easier to navigate.

Although alternative formats were focused upon in this talk, there are a number of other services the Libraries Accessibility Service can provide. They are first and foremost a point of contact for students for any queries about library accessibility, not requiring a referral, and can provide induction sessions and face-to-face meetings. They also work with other librarians across the Cambridge libraries’ network, providing both an accessibility service area, on the CUL intranet, and an Accessibility and Inclusivity Cambridge Libraries Toolkit, available publicly. They also embed in other groups, providing talks and training, and have a substantial LibGuide, which details Cambridge library services from the perspective of accessibility, linking to various resources across the libraries (such as individual libraries’ accessibility plans).

Thank you to the Libraries Accessibility Team for such a wonderful talk and for the Cambridge Library Group for organising it!

Links and resources:

- Contact address for the Libraries Accessibility Service: disability@lib.cam.ac.uk.

- Libraries Accessibility Service LibGuide

- Accessable.co.uk University of Cambridge – a website detailing how accessible various Cambridge Uni buildings are, including libraries

- Accessibility information for Cambridge Colleges

- RNIB Bookshare

- Abbyy FineReader PDF

- The Social Model of Disability

- Video: JAWS Screen reader demonstration

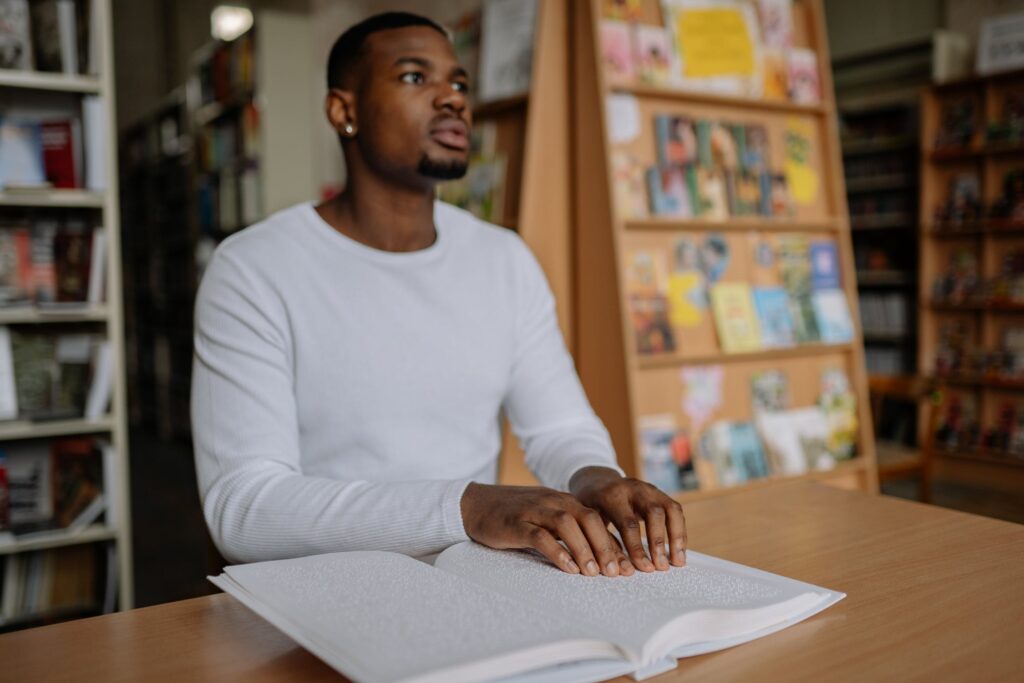

- Video: Refreshable Braille display demonstration