Tour & History of the University Library

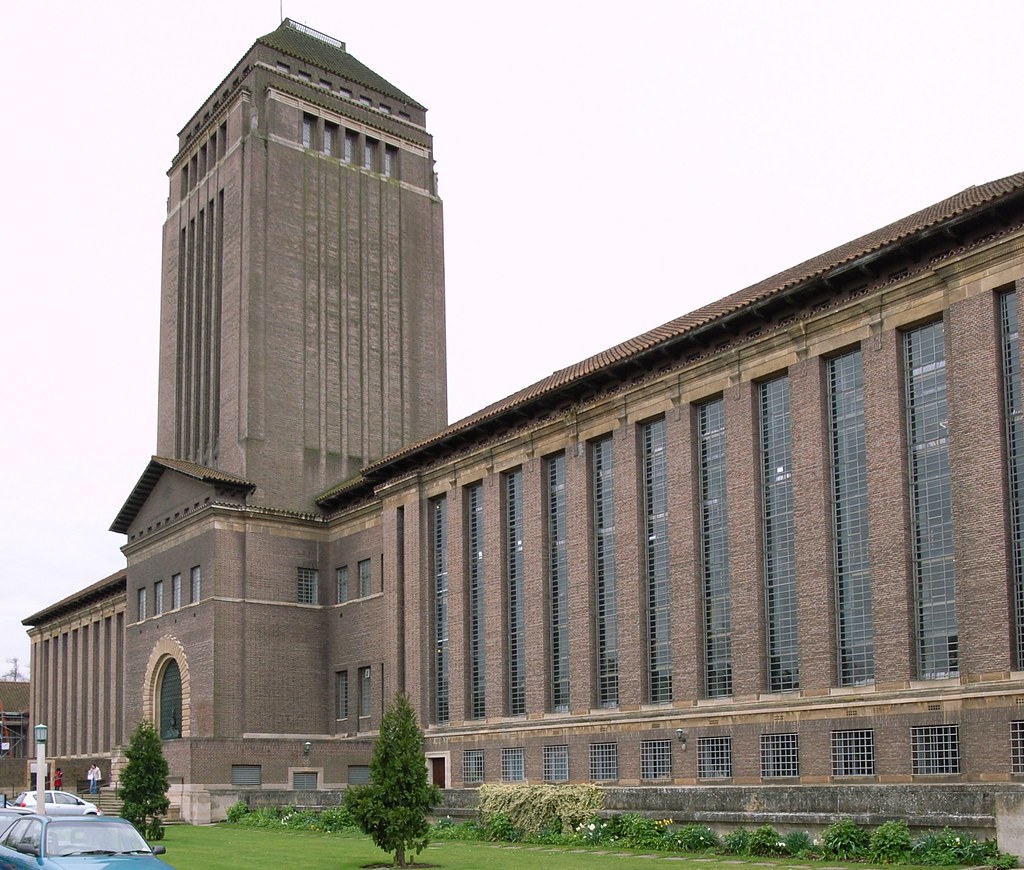

In mid-November we attended a jam-packed day-visit to the University Library. For many of us, this was our first voyage into the soaring entity that is the University Library. For myself, I was a student at Clare College, and spent the last three years in Memorial Court of Clare, literally stationed across the road; the University tower was a permanent fixture of my skyline and my life. Yet, for us all, this trip was eye-opening, not just about the University Library themselves and their unique collections, the intricacies of the space and the work taking place within it, but also to the plethora of careers and people that go into running a library on this scale, and which are pathways available to us in our future careers. This peak behind the scenes was enriching and exciting, especially as so many departments kindly opened their doors to us.

We later learnt, in our tour with one of the Library Assistants that kicked off the day, that the sky-scraper effect of the design is an intentional part of the architecture at the request of the donor (The Rockefeller association), and that the UL shares an architect (Sir Giles Gilbert Scott) with the Tate Modern in London; we got to appreciate the souring effect of the tower at the conclusion of the day (but I will leave that to Zia to explain in part two!). A fun fact we learnt while in the basement, exploring the underground storage system and the processes of book collection and return in the request element of library use, was that this architect also designed the phone box, and motifs of this design can be spotted all around the university library, most notably in the use of one as a drop-box, but also in the structure of glass in the doors, in the shape of plant pots, and more. Keeping your eye out for these motifs is a fun way to explore the library that I highly recommend. Liam kindly, and very helpfully, also organised our movement throughout the day between the many departments we got to visit.

While leading us around the building, our guide intertwined the history of the library with the actualities of their current use, such as in the catalogue room, where he explained how the physical catalogue was central to library use, as well as explaining the cut-and-stick approach to their creation, which he placed on a timeline with modern digital cataloguing practices, while still stressing the importance of a physical catalogue to library users and staff alike today. This highlighted to us how our role in libraries, and the way these institutions are run, will echo throughout the future of these collections and the way they are used; take Henry Bradshaw, the librarian from 1867-1886, who established many procedures and structures that remain in today’s practice.

Two major moments in the history of the University Library were explained to us as we walked along a staff corridor in the basement, with photographs of the construction and development of the library running alongside us: the introduction of the Copyright Act in 1710, which saw the University Library anointed as one of the nine privileged libraries of copyright deposit which makes them entitled to a copy of every book published in the UK; and the completion of the creation and move to the new Library in 1934, with the aim of transforming the library into a space that facilitated and cultivated scholarship. Our guide highlighted an image of a cart containing books, being drawn by a horse, and embellished how over 600 trips were required using the horse and cart method to move the library collection to the new building in the 1930’s (thankfully there were only two book fatalities in this process! Sadly, these books were claimed by the river – oops!).

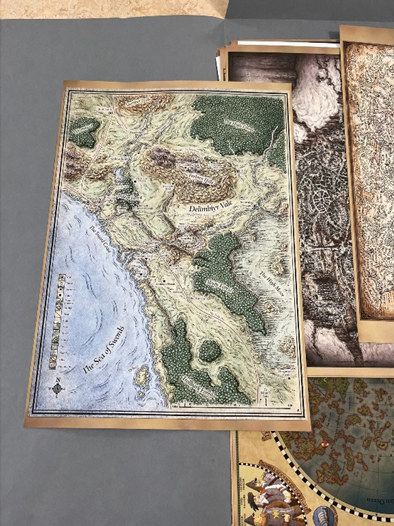

The Map Room

Our first departmental stop was the Map Room, where the Maps Librarian had laid out a selection of maps held in the collection, ranging from a medieval map of Constantinople, marked with red crosses to show the location of templars, to the continuous scale map projects of the 1850’s/60’s, to ground intelligence soviet maps. Being able to see these objects and see first-hand the wide range of material that comes under maps, as well as the way maps morph to fit purpose was fascinating. The Librarian explained how map curation techniques develop in relation to printing techniques by showing us examples of lithography, tooling, hand-painting, and more. He also explained that maps develop in response to intention/requirement; this raised our awareness of a critical understanding of maps, as holding a tension between the perceived empirical truth of them and the purpose of them. To highlight this, we looked at two maps in comparison; a medieval map of the sea, awash with mythical beasts that pose threat to seamen, next to a modern nautical map, which focused on empirically mapping the depth of the sea.

A particular highlight was the fantasy maps which the Librarian got out at my request. He kindly took the time to explain how he pursued online fantasy map designers who created these maps as a hobby in order to curate a collection of them to be held by the library for prosperity. These maps indicate a great amount of modern interest, knowledge, artistry and work that continues to thrive in map making. He also asked us (and in turn I now ask you) to donate any fantasy maps we have from video/board games and such to further enrich this area of the collection.

Here we also considered, and saw, how library practices respond to different types of collections and the items they contain. The first challenge is that of form and format; when the object is not a typical book it requires flexibility of storage, such as tubes and large drawers to preserve them. Another element is how cataloguing is modified to cover the data that users need to know about these objects; in this case, there are specific unique fields in Alma for cataloguing, but Ian highlighted how much of a key role card cataloguing retains in this type of collection by showing us their catalogue drawers. We also heard how special collections like these are responding to, and utilising, modern developing technologies, as with the open-source project with the British Library which aims to create a digitally stitched map of the world. In this way, we saw how librarianship practices are responsive, how they must, and can, be flexible to special collections, and how they continue to be malleable with the introduction of new technologies.

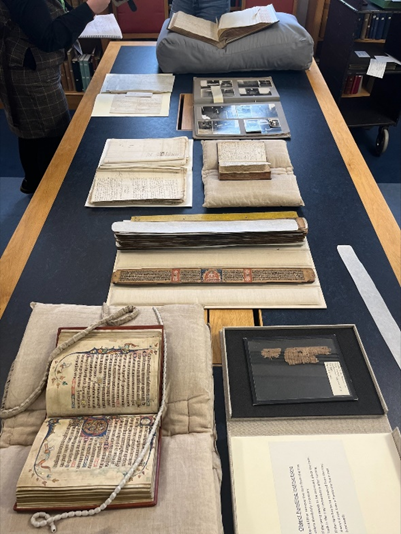

Manuscripts & Archives

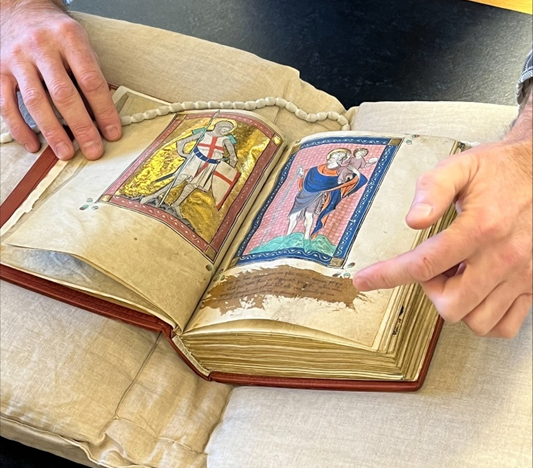

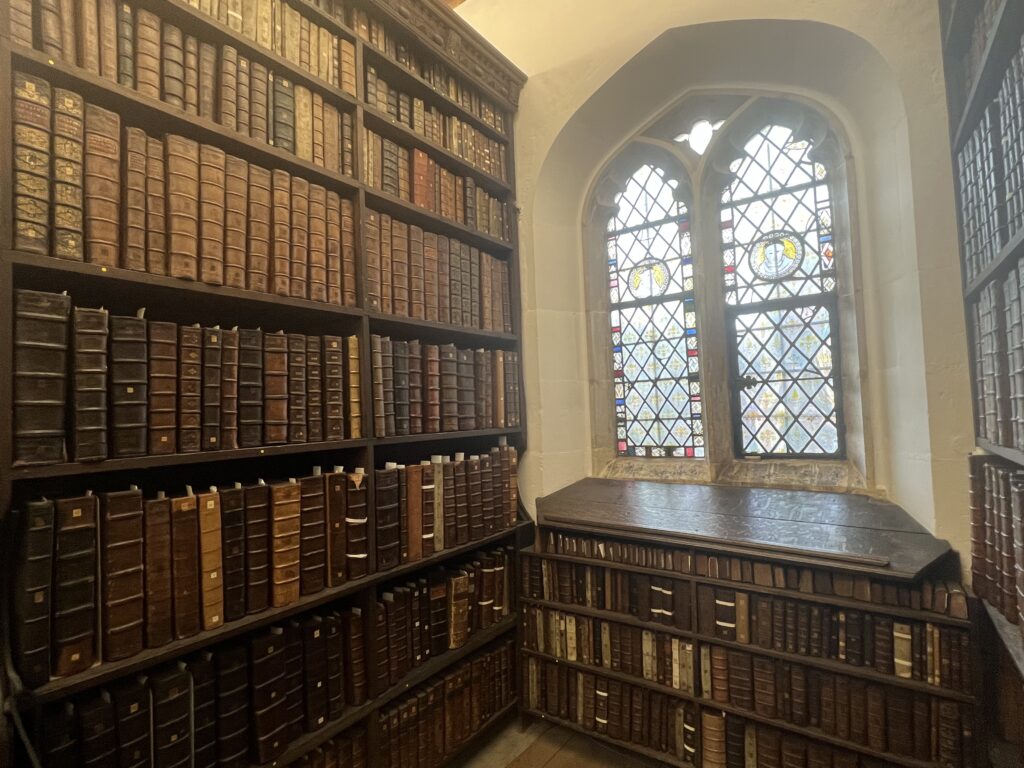

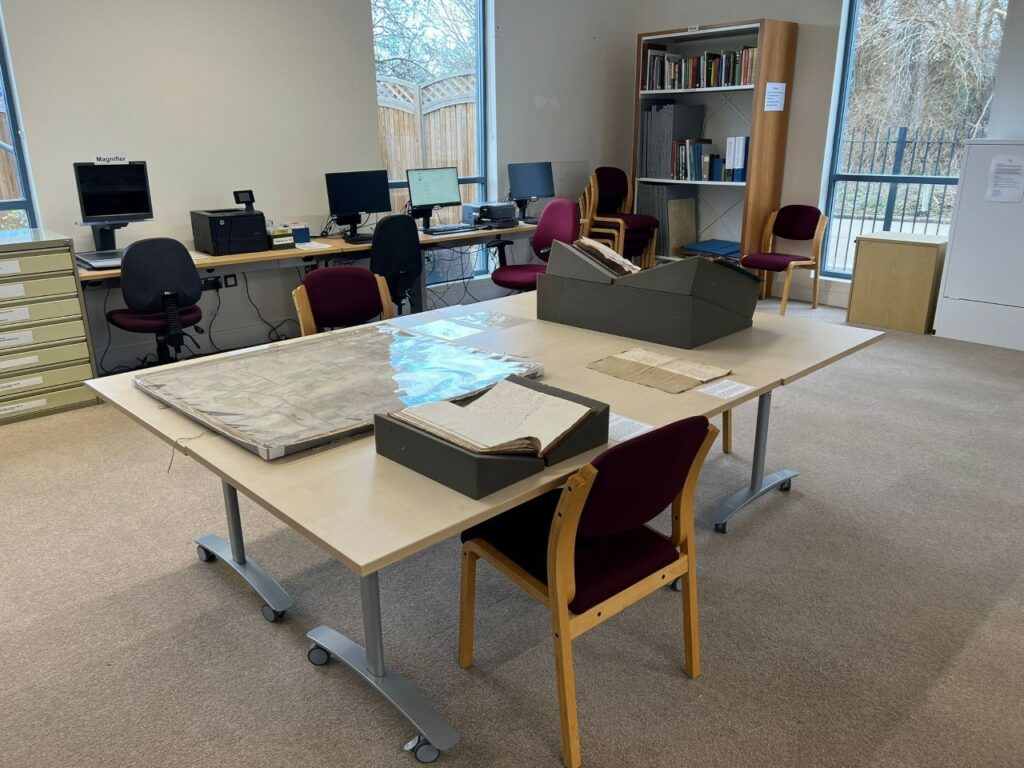

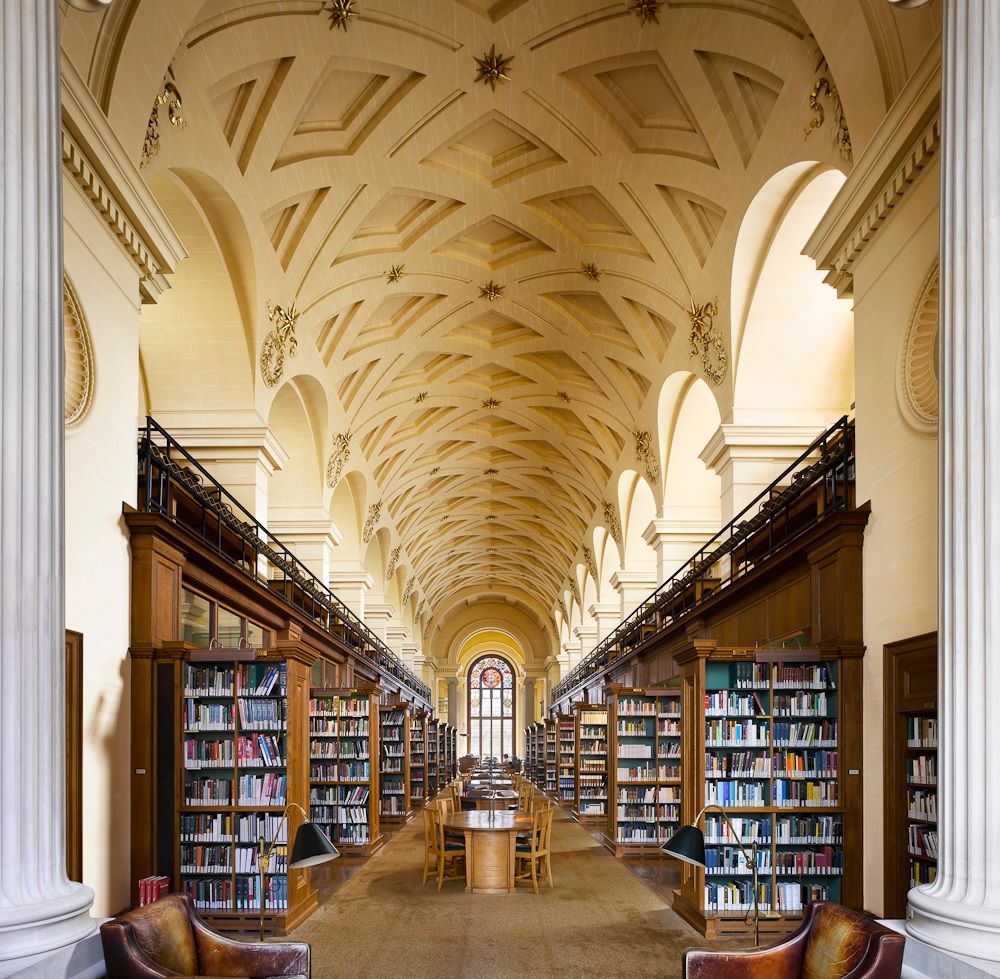

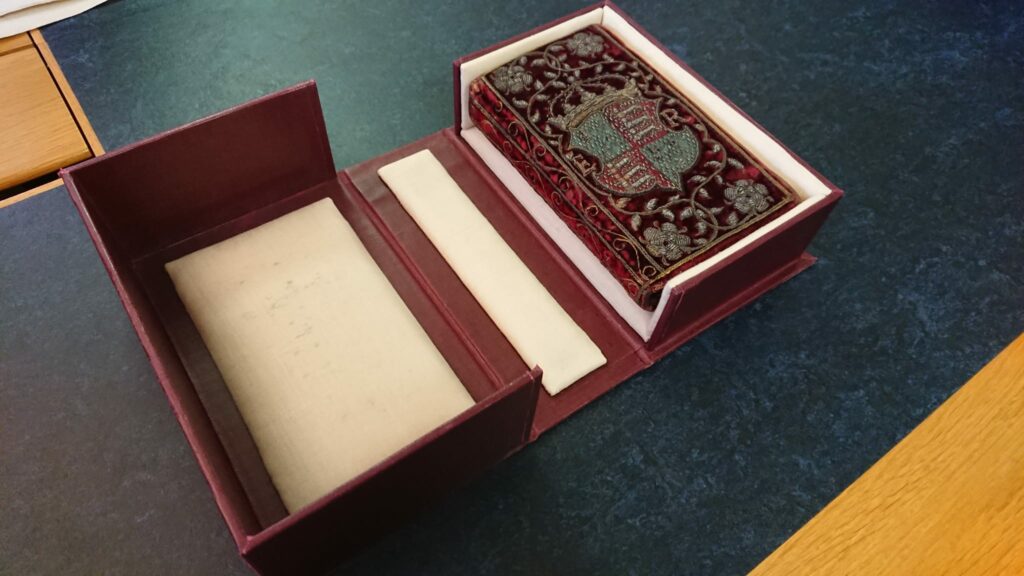

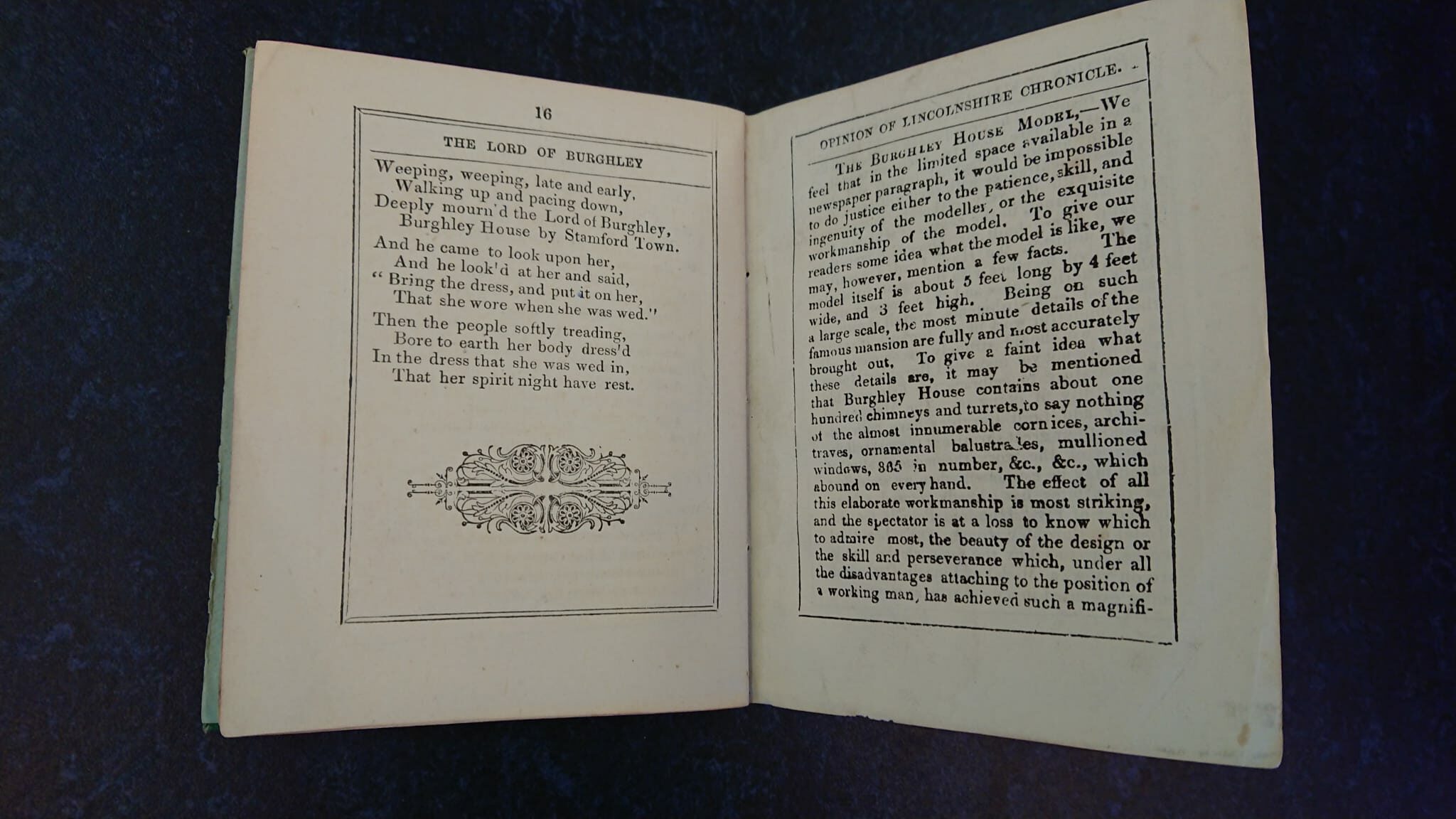

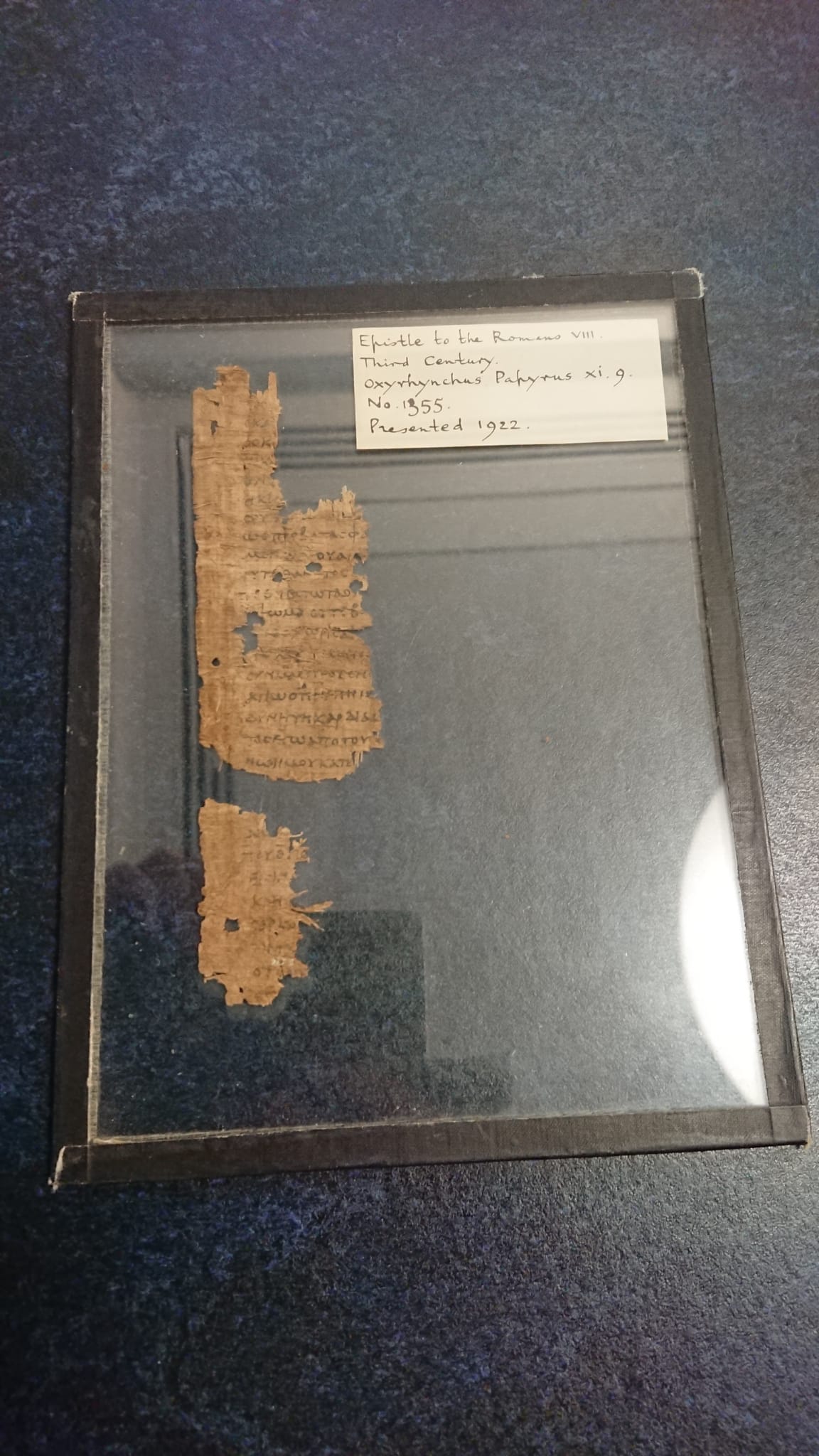

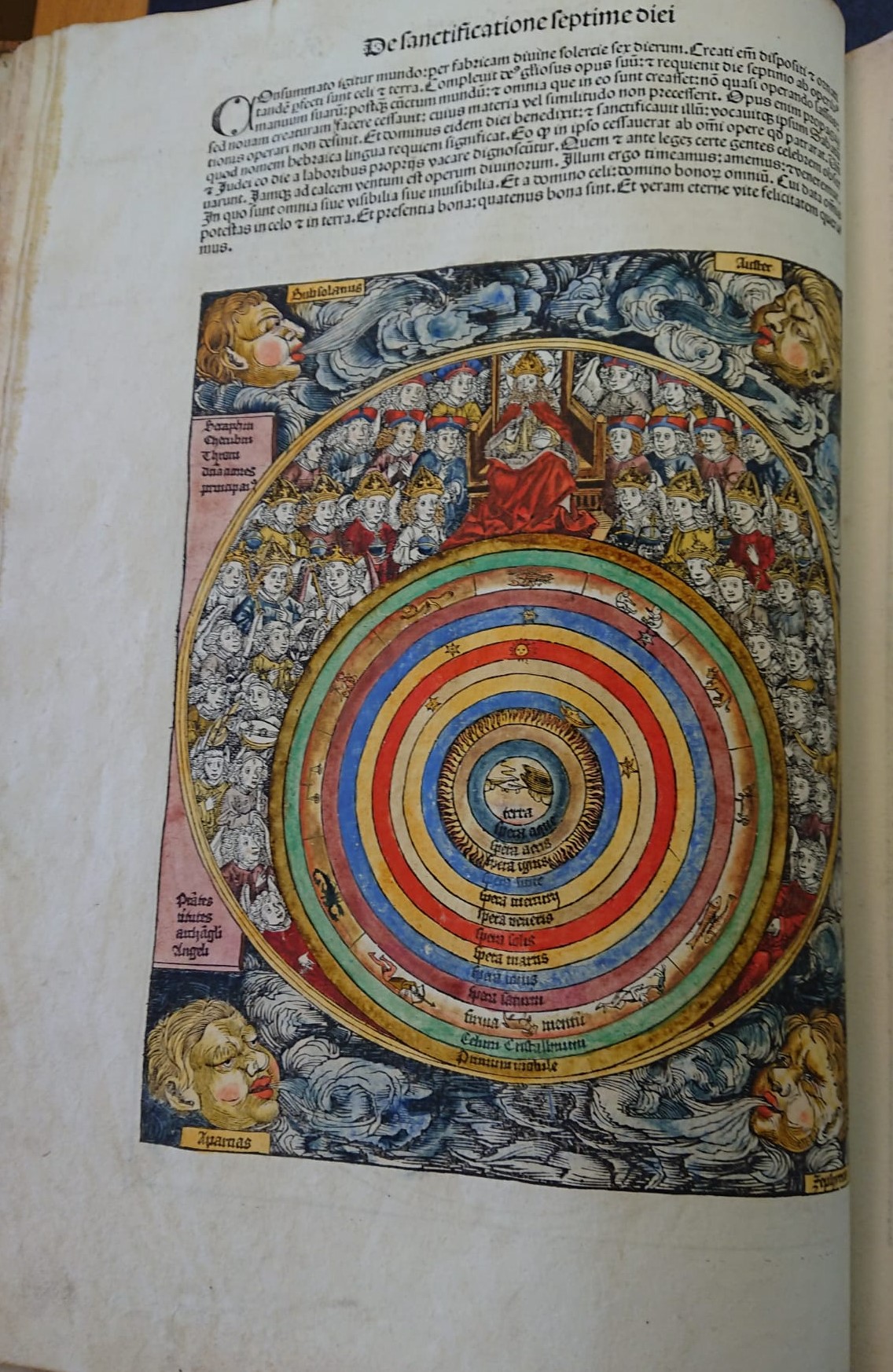

After a tea break in the library café, we arrived at potentially our most highly anticipated stop of the trip; the manuscript reading room. As an undergraduate student at Cambridge, I had personally been given access to this room in my final year to use a manuscript from the collection for my dissertation, but even that couldn’t have prepared me for the wealth of treasures the Archivist had prepared to show us. In his selected array, the Archivist took us simultaneously through the history of the development of the manuscript and archives collection in the library, as well as the very history of books themselves. He began by unveiling from an unsuspecting box a glass case, containing the earliest item from the collection: fragments from the Oxyrhyncus papyrus collection, dated to 300 AD. We were then shown a Buddhist illuminated manuscript, which had a format which none of us had seen before, and which we were fascinated by as he carefully removed each strip of palm to reveal the next in the Poti format sequence; it demonstrated the wide array of forms that books have taken over centuries, and geographies. Dated to c.1000, this manuscript of the Perfection of Wisdom in Eight-Thousand Stanzas is a jewel of the library, as it is one of the oldest illuminated manuscripts from India in Sanskrit.

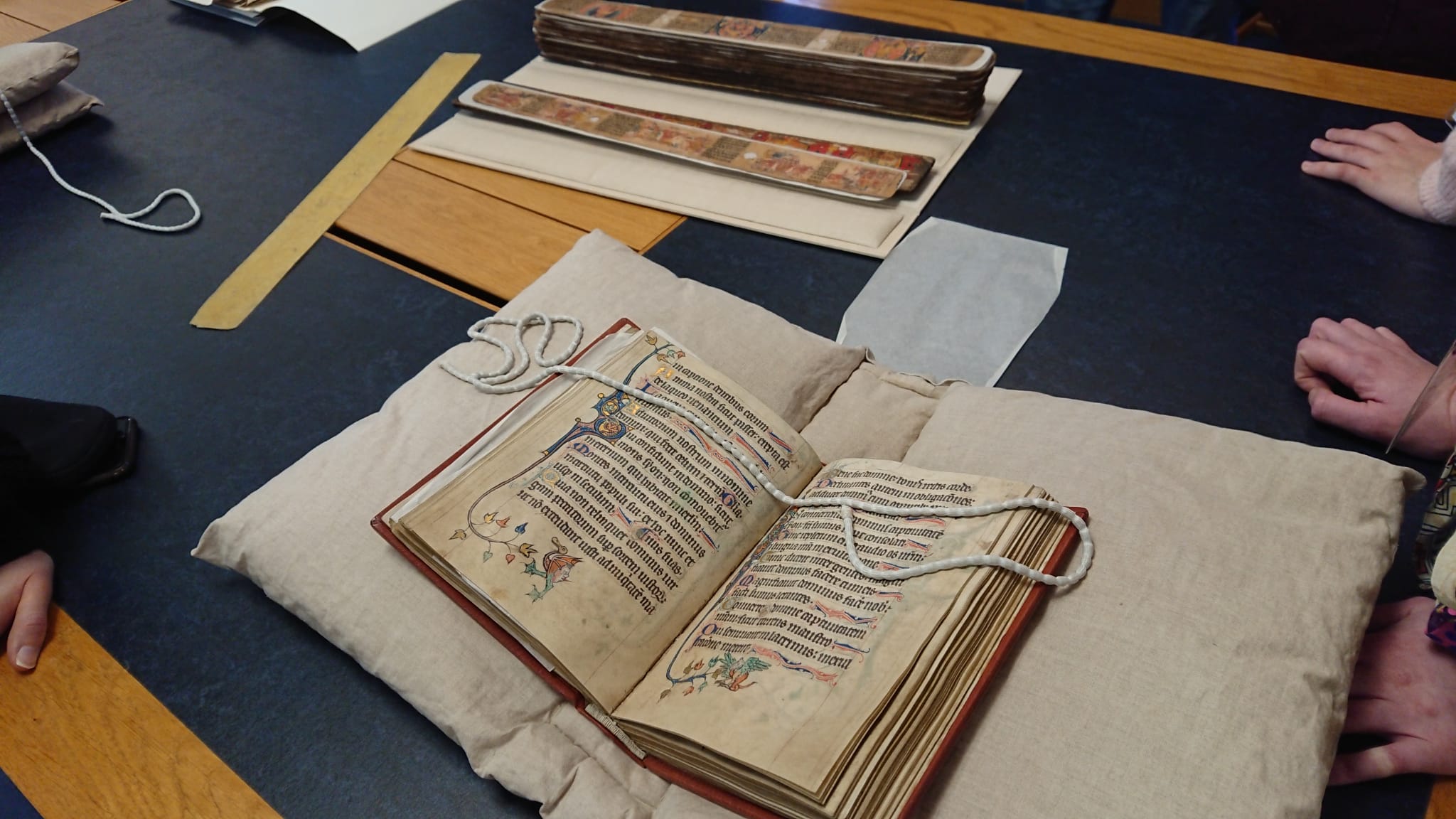

Next was a beautifully sumptuous medieval Book of Hours, dated to the 14th-century, gilded with gold, and rich in colour, with many playful marginalia scampering around its pages, and a provenance of Alice de Raydor. He explained how the manuscript reveals the history of its creation, as with the tools depicted in the marginalia placing its creation in East-Anglia, and its story of preservation, highlighting the marks left from Victorian attempts at conservation on one of the pages, where a cleaning fluid has permanently stained the text beneath an illumination. In this way, we learnt how conservation practices, special collections, and the thought that runs them, have morphed across time, and how we might play a roll in their future. These books may only be in our care for a short while of their lifetime, but it is a Rare Books Curator’s role to care of them, and to facilitate scholar’s access to them both now and for posterity.

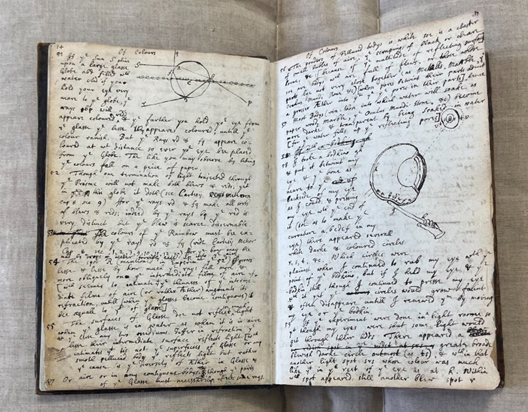

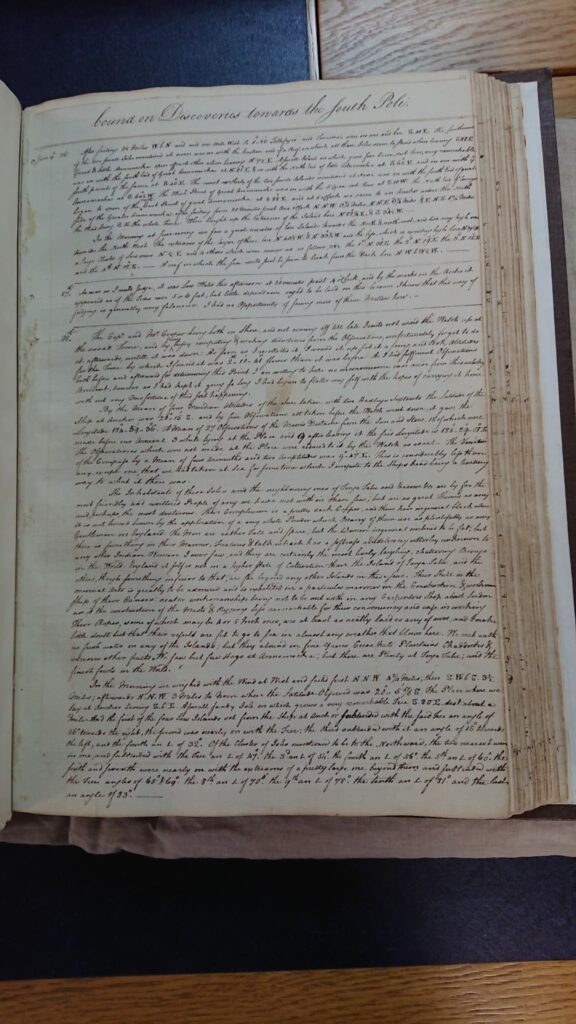

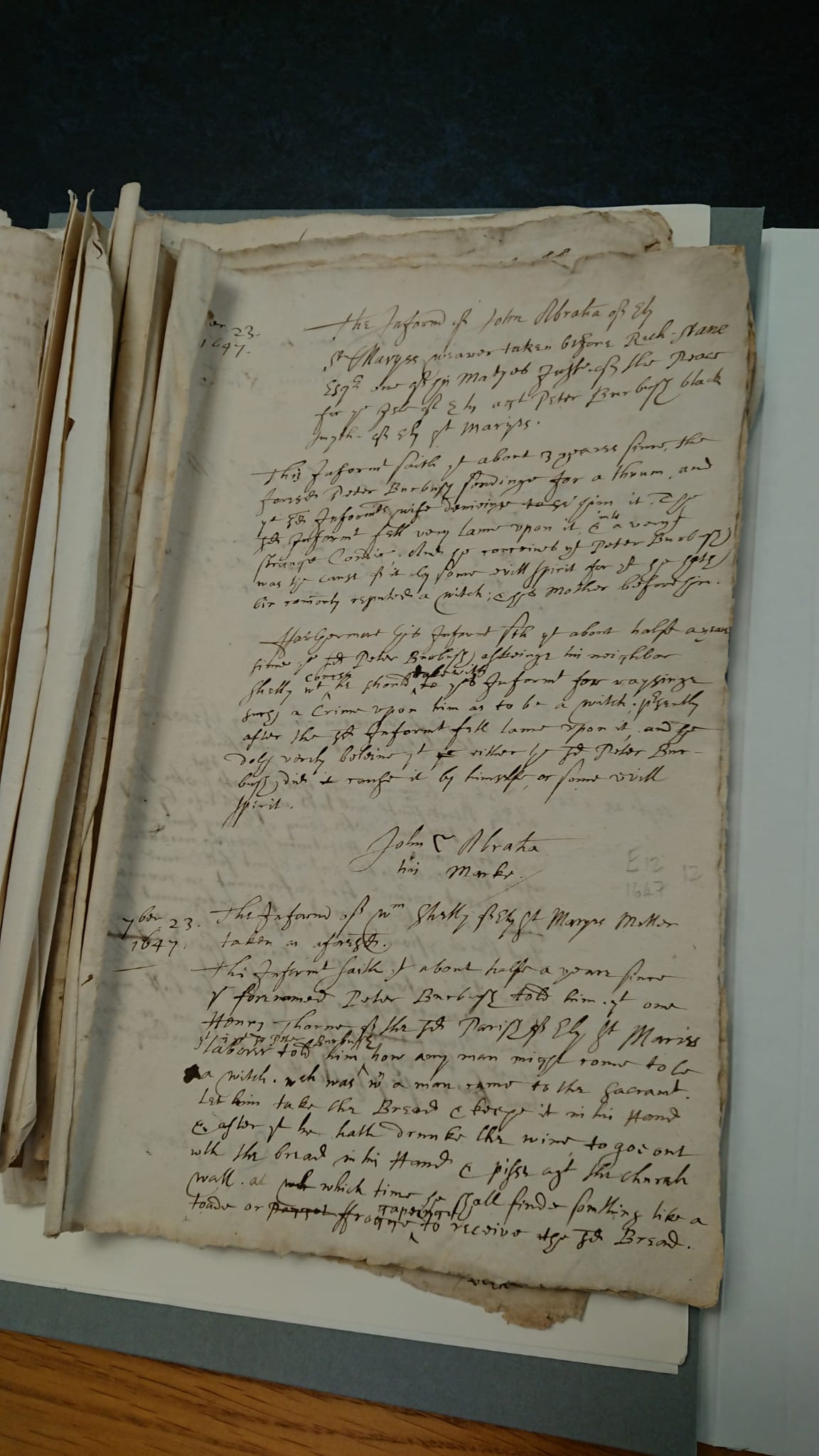

In this display we were also shown a remarkedly broad selection of the type of records archived in the University Library: from Isaac Newton’s student notebooks, marking his experiments on his own eyes with a bodkin that were not for the squeamish; to ship logs; to Charles Darwin’s prose and cons list of marrying, which included as a pro “better than a dog anyhow” and concluded with the decision to “marry, marry, marry Q.E.D”. We began with the Ely diocese records, which were highlighted as a key resource to social historians, as the records go back to c.1200 and track the complex changes of the concept of justice through the court records. Specifically, we were shown a selection of records from the 1640’s that related to witchcraft, including the Archivist transcribing a section of a spell to us which involved a man taking eucharist bread “in his hand”, feeding it to a frog or toad, and “pissing[ing] against a church wall” in order to perform magic. Weaving a path through the vast collections, we were introduced to a collection held by the library relating to The Goligher Circle, and their paranormal investigations in the 1920’s. This featured photographs that claim to evidence ‘exuding ectoplasm’, which the library also has a sample of, floating in a bottle.