Although not one of the libraries we were scheduled to visit for our traineeships, the librarian at St Catharine’s kindly extended an invitation to visit their library, which we eagerly accepted. We’re all very grateful for any opportunity to see different libraries, and with every Cambridge college library being unique, this was a great chance to see how another library works and how they support their students.

St Catharine’s has two student library spaces – the eighteenth-century Sherlock library holds the collections for Modern and Medieval Languages and Literature, English, and Art, whilst the newer 1980s Shakeshaft library contains the material for all other subjects.

We began our tour at the Shakeshaft library, marvelling at how much light the big windows at the front let in to create a bright study space at the front of the library. The librarian confirmed that both the long line of desks in front of the window and the comfy seating area beside it were popular spaces in the library. Our attention was immediately grabbed though by the large duck sat on the sofas, which had been given the perfectly accurate name ‘Big Duck’. Big Duck is a great initiative run by St Catharine’s library – the small tag around its neck states that Big Duck is ‘available for gentle hugs’ and that students can take it to sit with them whilst they’re in the library, having it serve as a giant study-buddy to support them through times of stress.

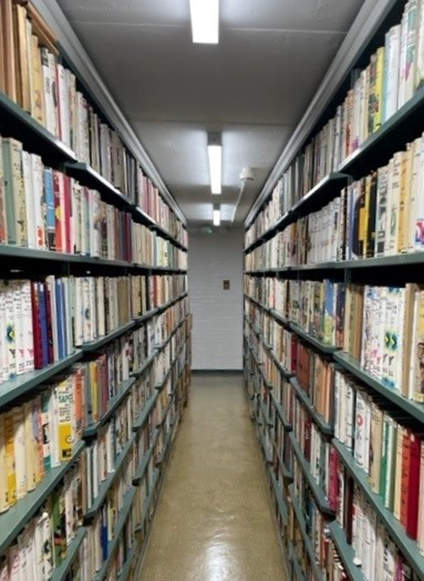

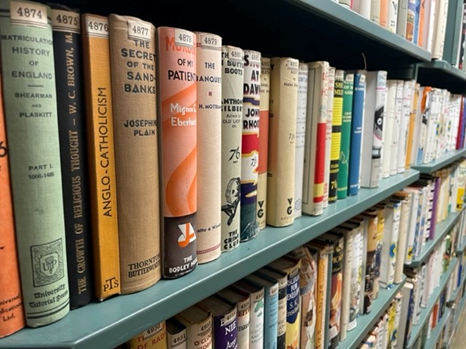

The maze-like layout of the shelves in Shakeshaft produces lots of little nooks you can get lost in exploring books, with most of the study spaces tucked around the edges. The tall shelves actually support the ceiling of the library, and are therefore a permanent design feature.

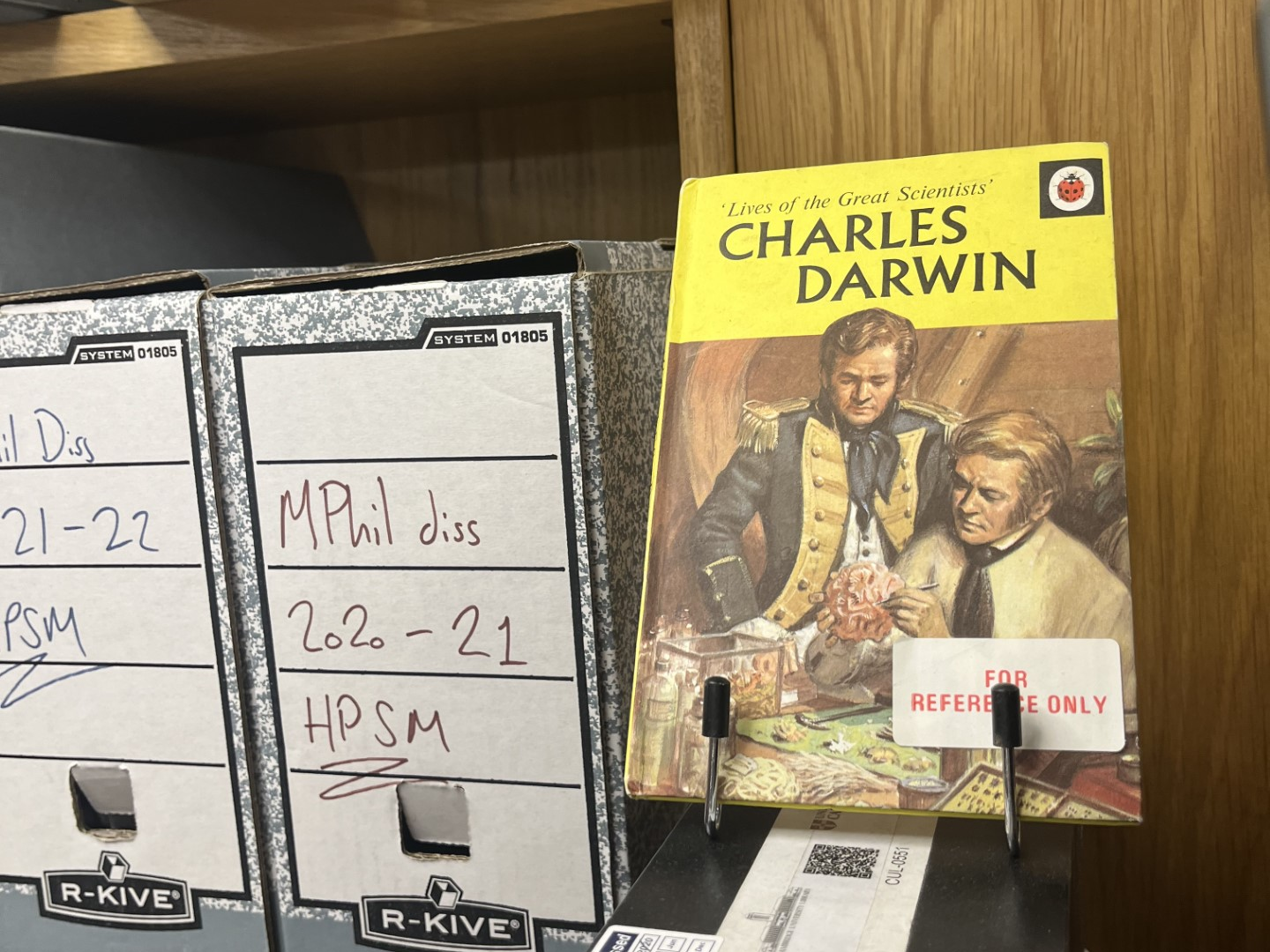

Another interesting initiative the library has introduced is how they loan their wellbeing and light reading collections – students don’t take the books out on their card but instead borrow them anonymously on a basis of trust for as long as they need. This is a great way for students to feel comfortable borrowing any books within these collections, and helps improve their accessibility and inclusivity. The wellbeing and fiction books themselves were all nicely organised on the shelves, further making it an approachable and welcoming space to borrow from.

As we circled back to the front of the library, we were shown the display on Thomas Sherlock, a former Master of St Catharine’s, who left both money and his personal book collection to the college library. Alongside an image of Sherlock’s portrait, painted by Jean-Baptiste van Loo, the library team had done some detective work and managed to find a finely decorated book in their collection which looked very similar to the one he is holding in the painting – the first of four volumes of ‘Several discourses preached at the Temple Church’ by Tho. Sherlock, printed 1754-58.

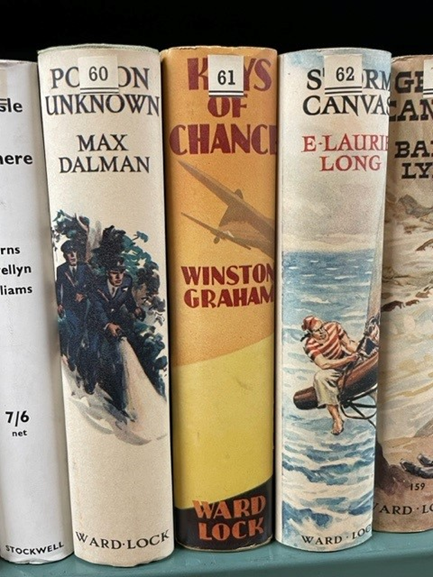

The display was a good introduction to the name behind the Sherlock library – St Catharine’s older library space and our next destination. With its high white ceilings and original dark wooden shelves, the Sherlock library is a beautiful space which perfectly evokes those aesthetic academia type vibes. The librarian emphasised the importance of keeping this as a working library rather than as a place for the rare book collection, providing the students with a usable study space and a different library environment to work in.

Some of the lovely features of the Sherlock library include: window seats, where students can sit and study whilst looking out over Main Court; both old-fashioned green banker’s lamps and modern museum desk lights – adding to the ambience; and original bookshelves with rests for reading. The librarian pointed out that the shelves still retained the eighteenth-century labelling at the top, highlighting again the history of this space and its longevity as a library. We were also shown the two different methods for accessing the higher to reach books: the first a small stand with a pole to hold on to (which turned out to be more secure than it looked!), and then some sturdier looking steps, which of course we tried as well!

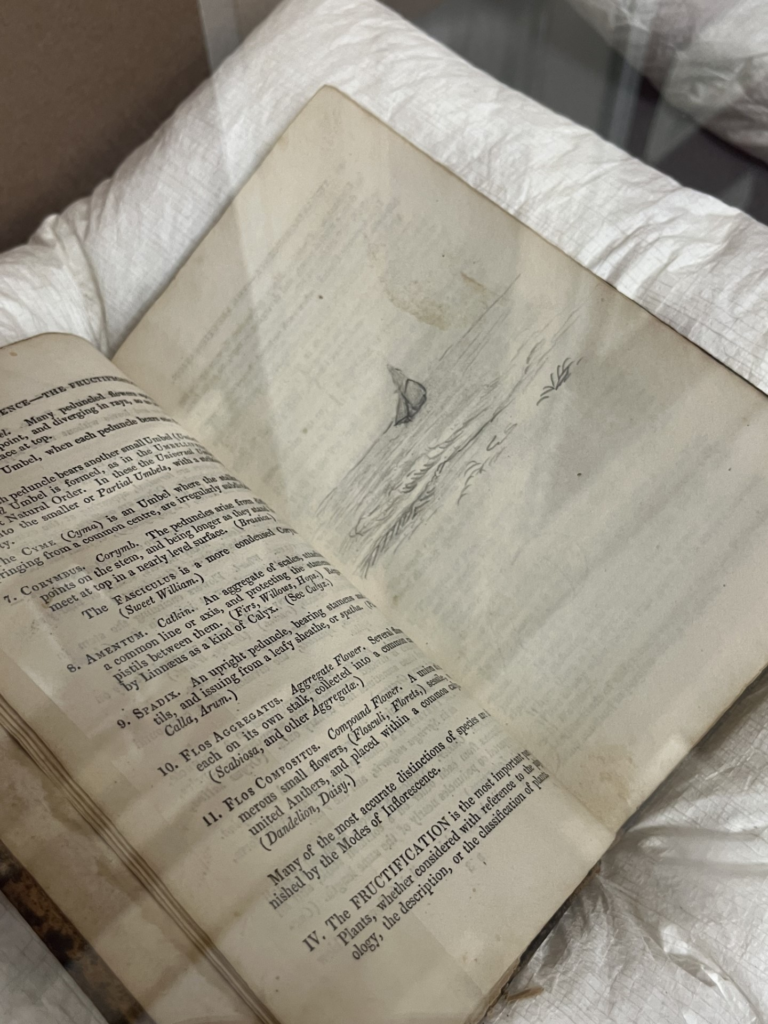

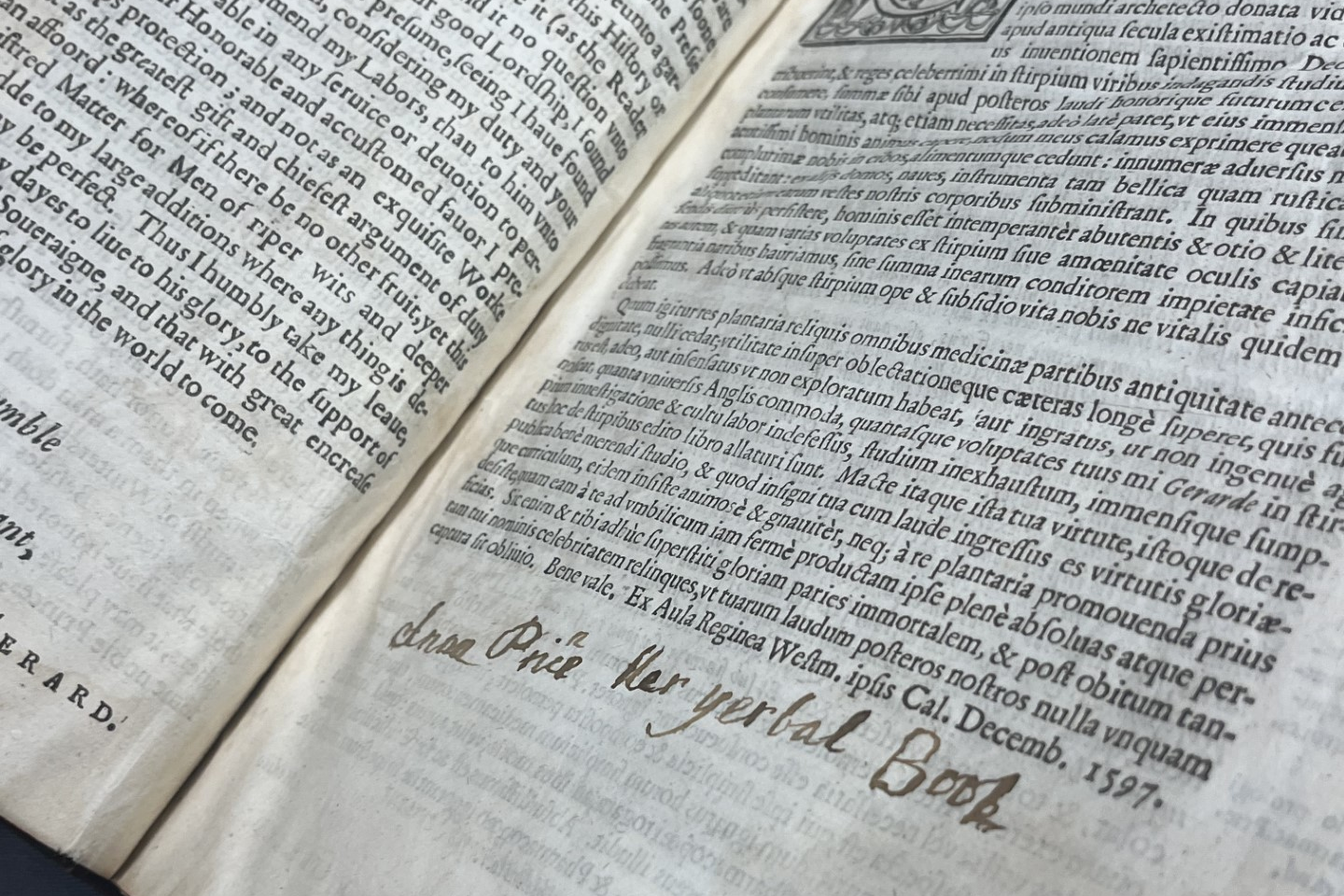

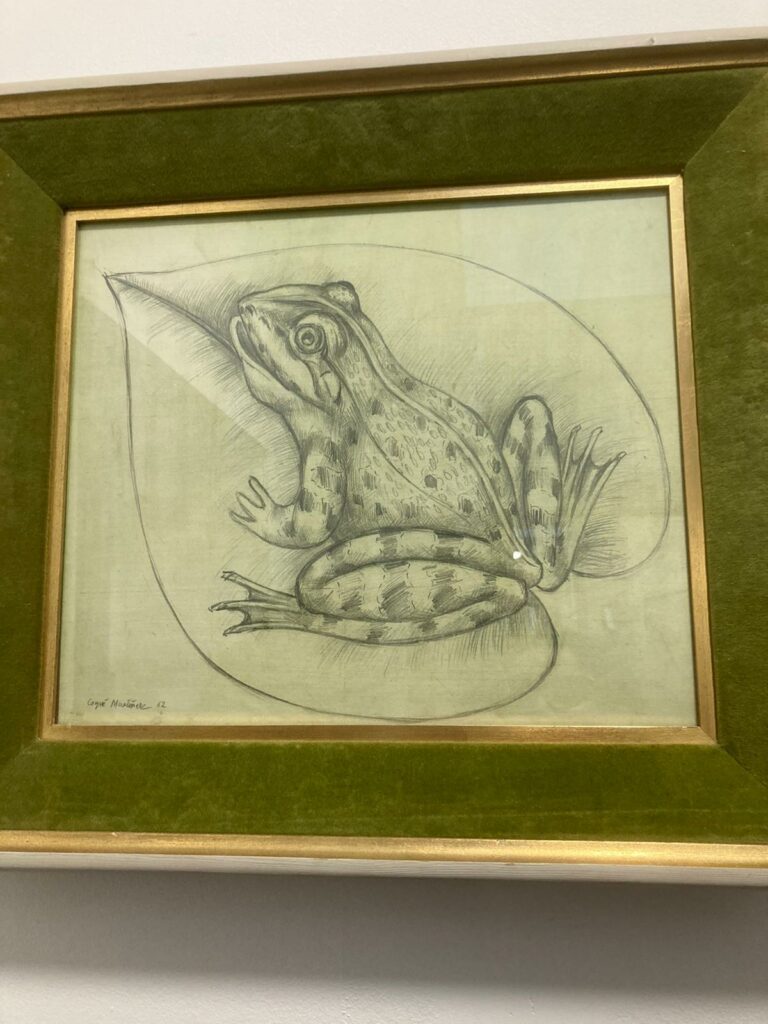

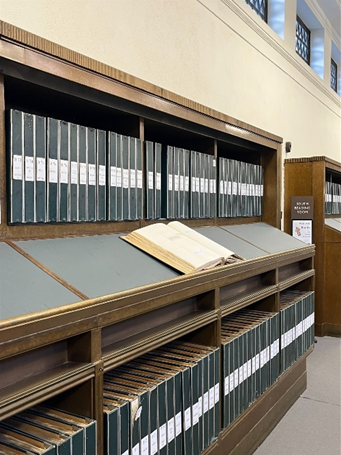

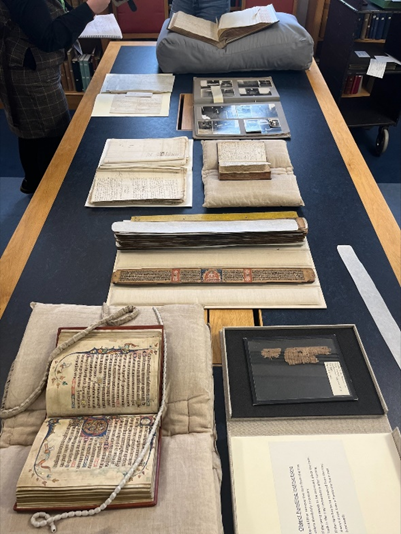

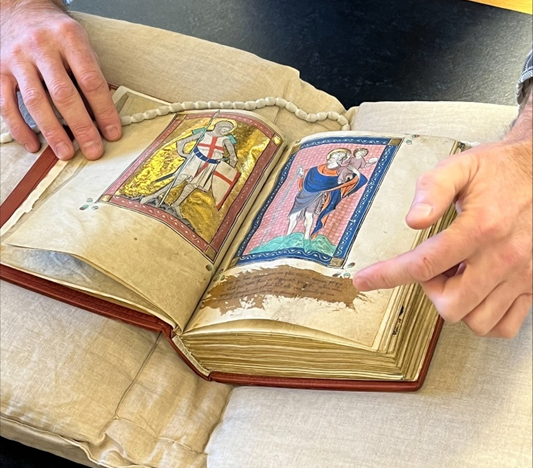

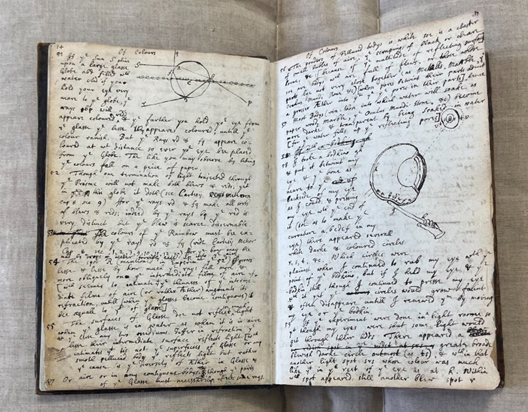

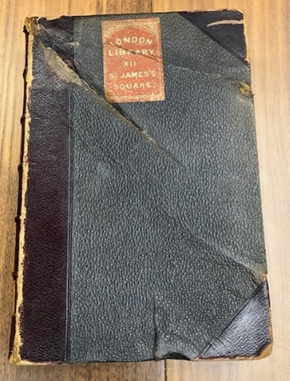

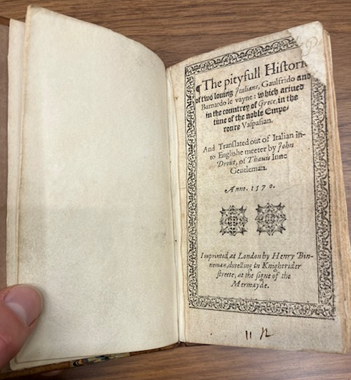

Leaving the warm and cosy Sherlock library behind, our final stop was the new reading room. This is a wonderful space, providing plenty of room to study requested books and manuscripts from St Catharine’s special collections. The librarian had laid out several books for us to peruse, all notable for either their unique subject matter or for their condition. For example, a copy of the German book ‘Denkmäler Provenzalischer Literatur und Sprache’ by Hermann Suchier, previously owned by the London Library, had somehow been run over by a train – it is still in one piece, albeit slightly squashed! Another book which we all enjoyed looking through was ‘The Pityfull Historie of two loving Italians, Gaulfrido and Barnardo le vayne…’ by John Drout, a sixteenth century LGBT text written in rather questionable verse.

Overall, we had a wonderful time looking around St Catharine’s and managed to squeeze a lot in to our brief visit! We were all impressed by the student focused approach of the library team, and the different wellbeing initiatives they have put in place. Thank you to the library team for inviting us!